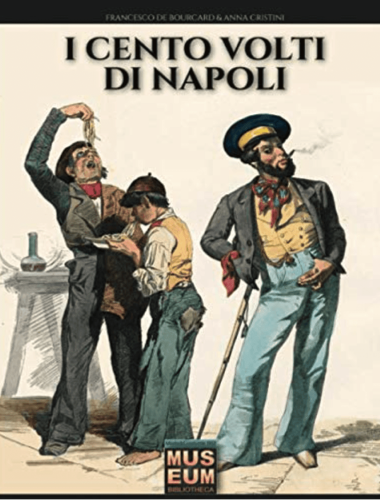

‘See Naples and die’, as Goethe, below, left it. I first landed in Naples about 20 years ago? An unsafe city. That was my first impression of Naples. Italy as a whole is notoriously unsafe, but Naples in particular seemed very dangerous. But Naples is a special city. The houses lining the narrow streets are beautifully coloured, the sun is shining, the food is delicious and the people are friendly. The sea and the volcano. If you go to Naples, you will definitely like it. (Except for the security).

The Asian people are often mistaken. When they hear the word ‘European peoples” imagine a tall race like Germans or Scandinavians. However, when you actually meet Italians, they are not so tall. The same is true in Naples and Spain. They (Latins) are almost the same as the asian. However, their physique is different. In particular, it is said that the thickness of the chest area is different even among ordinary people. However, there are some things that I think the Asian benefit from. The fact that they are close in height to them makes it easier to match suit and jacket sizes, which is a big advantage. You will get the best technology and the best material products.

But… Neapolitan tailors are usually the wrong size.And delivery times. Why do they make mistakes? There is only one answer. Because they are Neapolitans.This is the answer.

In fact, I feel that the history of the country of Naples can be considered a different country from other Italian regions. Because of the dazzling tropical sun that makes the colouring look distinctly different. Because of its proximity to Africa, it is heavily influenced by Islamic culture. Because it is a poor place with less industrialisation than northern Italy, which led to the development of manual labour by hand. And that there were long-standing links with Spain and the Habsburg Family. These are possible reasons.

Vincent Van Gogh said.”There is no blue without yellow and without orange.”

The dazzling rays of the sun will be shining on Naples today.

Naples was founded as a Greek colony in the 8th century BCE, and it was known as Neápolis, which means “new city” in Greek. The Greeks established a thriving city on the site, which became an important center of trade and culture in the Mediterranean. Over the centuries, Naples was ruled by a succession of different powers, including the Romans, Byzantines, Normans, and Spanish. Each of these groups left their mark on the city, contributing to its unique cultural heritage. During the Renaissance, Naples was a one of the center of artistic and intellectual activity, attracting some of the greatest minds of the time. The city was also a hub of political and religious turmoil, with conflicts between various factions vying for power and influence.

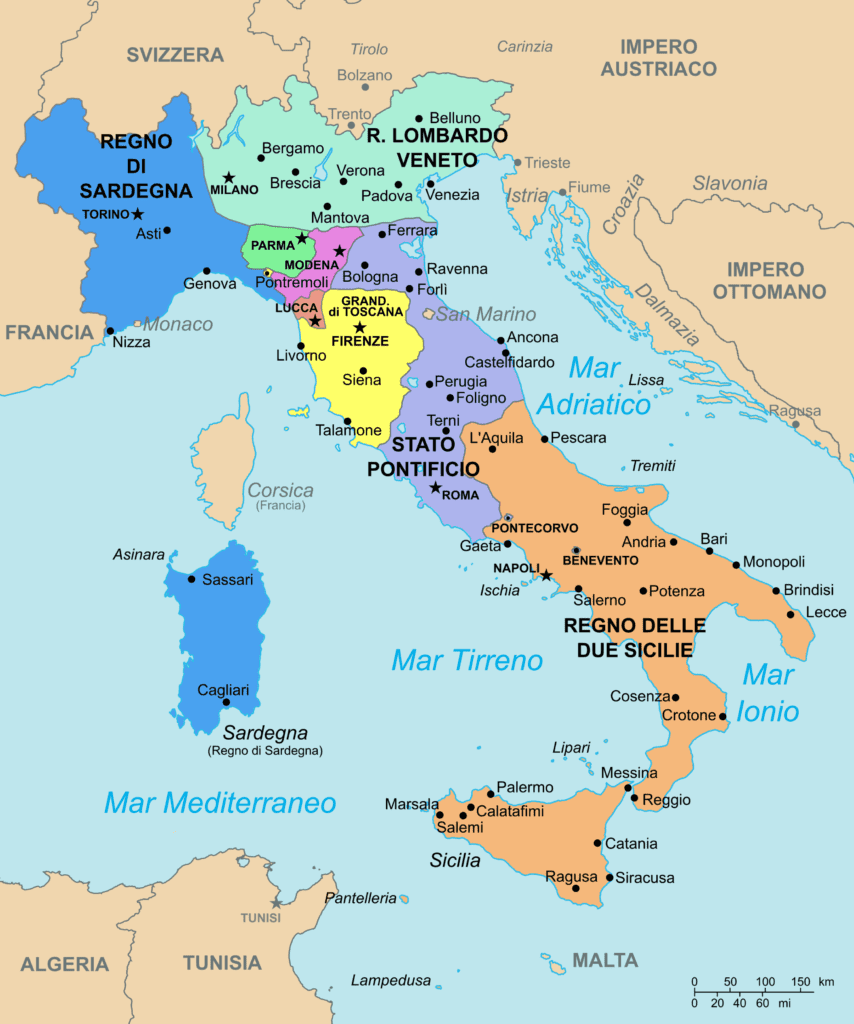

In the 19th century, Naples became a center of the Italian Risorgimento, or nationalist movement, which sought to unify Italy under a single government. The city played a key role in the movement, with many of its citizens actively supporting the cause. As of 2021, the population of the city of Naples is estimated to be around 950,000 people. The wider metropolitan area, which includes surrounding towns and municipalities, has a population of around 3.1 million people.

When talking about the Italian textile industry, one must first talk about the ‘furos’ or “fullo”. Without them, the Italian textile industry would not have developed. Their profession was so important.

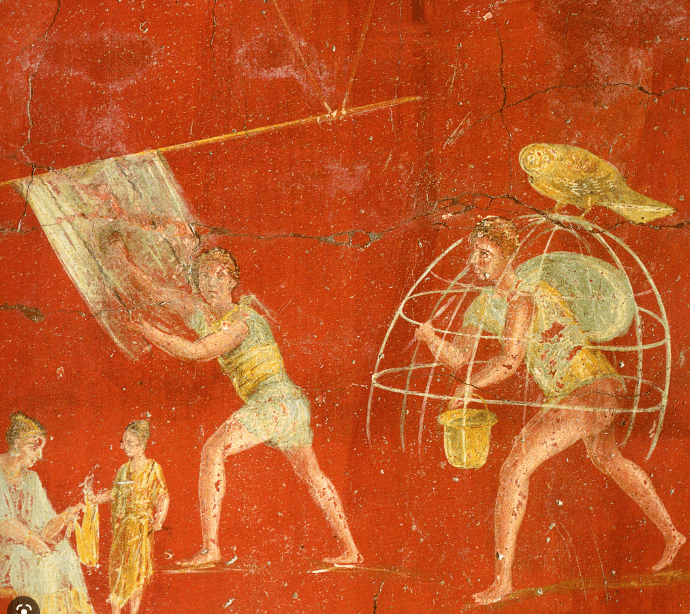

Clothes were processed in small tubs that were placed in niches surrounded by low walls. The fuller would stand with his feet in the tub, which was filled with a mixture of water and alkaline chemicals (including ammonia derived from urine in some cases), and then trample the cloth, scrub it, and wring it out. The goal of this treatment was to apply the chemical agents to the cloth so that they could dissolve greases and fats. These processing stations are typically called “treading stalls,” “fulling stalls,” or, erroneously, “saltus fullonicus.” They were common in fulling workshops and are often used by archaeologists to identify fulling workshops in archaeological sites.

Once the clothes had been treated with the alkaline chemicals, the dirt that had been dissolved had to be washed out. This was done using fresh water in a complex of large basins that were often connected to the urban water supply. The typical rinsing complex consisted of three or four basins that were connected to each other. Fresh water would enter on one side of the complex, and the dirty water would exit on the other side. The clothes followed the opposite direction of the water and moved from the basin with the dirtiest water to the basin with the cleanest water. This process ensured that the clothes were thoroughly rinsed and cleaned before being dried and finished.

The last phase of the fulling process involved a variety of treatments, although the exact sequence is not precisely known and may have varied depending on the nature of the workshop and the requirements of customers.

One common treatment was brushing the cloth with thistles from plants and shearing it, as evidenced by finds in some Pompeian fullonicae. In addition, clothes were sometimes treated with sulfur to maintain their color. The cloth was then hung on a basket-woven structure called a viminea cavea, which can be seen in the figure above. Fullones added sulfur to white cloths as they knew that sulfur was volatile enough to destroy colors.

The clothes were also pressed in a screw press. Remains of such presses have been discovered at Pompeii and Herculaneum, and a depiction was found in a Pompeian fullonica and is now exhibited in the National Museum in Naples.

“Fullo”or “Fullones” were important in the textile industry of ancient Naples. They were specialized workers who carried out the fulling process on cloth, which involved cleaning and shrinking the fabric to create a denser, more durable material. The fullonicae, or fulling workshops, were typically located in urban areas close to the water supply, which was necessary for the fulling process. Fullones in ancient Naples were highly skilled and could work with a variety of fabrics, including wool, linen, and silk. The fulling workshops were important centers of textile production and employed many workers, including fullones, dyers, weavers, and spinners. The finished textiles were then sold in markets throughout the city and beyond. Overall, fulling played a crucial role in the textile industry of ancient Naples, and the fullones and fullonicae were key figures in this industry. It is no exaggeration to say that the foundations of today’s Italian textile industry started in these Roman times.

Dance scene and popular party in Naples Dancers of tarantella (tarantella, tarantella). Anonymous painting. 18th century Naples, Museo Nazionale di San Martino

The Umayyads ruled the Berbers in the Maghrib region of North Africa. They entered the Iberian Peninsula and destroyed the Visigothic kingdom in 711. Furthermore, raids by Islamic armies comprising Arabs and Berbers reached Sicily, and in 827 the Aghlab fleet of Tunisia, which was under Abbasid suzerainty, launched an invasion of Sicily, which was almost completed in 878 with the capture of Syracuse, and in 902 the remaining eastern part of the island Taormina fell in 902. Islamic rule then continued until the 12th century, and they often invaded mainland Italy, using Sicily as a base. The period of Islamic domination also brought new agriculture and economic development, especially in Palermo, where a unique fusion of Roman and Islamic cultures was formed.

Arabic painting made for the Norman kings (c. 1150) in the Palazzo dei Normanni, originally the emir’s palace at Palermo.

The Muslims brought irrigated agriculture to Sicily. The fields around Palermo were channeled, Persian reeds (sugar cane) and papyrus were cultivated along the water’s edge, and irrigation techniques were supported by advanced siphon technology of Persian origin. Along with this irrigated agriculture, the Muslims brought lemon, daidai, cotton, mulberry, dates, poison ivy, pistachios, papyrus, melons, rice and sugarcane, which were almost unknown in Europe until then. Silkworms were also introduced for silk production. This lush Sicilian landscape was maintained even after the Muslims disappeared in the 13th century.

The Normans moved into Sicily from 1061, eliminating Islamic powers, and in 1130 Ruggiero II founded the Kingdom of Sicily, which spanned Sicily and southern Italy. Under him, a bureaucratic system was developed, which reached its zenith in the 13th century when it replaced the Germanic Staufen dynasty. After its breakdown, the kingdom was contested by the French House of Anjou and the Spanish House of Aragon; In 1282, the islanders, dissatisfied with French rule, rose up in an uprising (the Sicilian Vigil), and the troops of Aragon of Spain, who came as reinforcements, ruled Sicily as it was, establishing the Kingdom of Sicily in 1302, while the Anjou family ruled only southern Italy, mainly Naples, as the Kingdom of Naples.

In the 15th century, the Aragonese kings, who ruled their home kingdom of Aragon and this Sicily, became increasingly powerful and took possession of Sardinia, and in 1442 they annexed the Kingdom of Naples. Here, a state was again established that ruled both Sicily and southern Italy, at which time it was officially known as the Kingdom of Both Sicilies.In 1479, when the Kingdom of Aragon and the Kingdom of Castile on the Spanish mainland merged to form the Kingdom of Spain, Sicily was also incorporated into the Spanish kingdom and became part of a maritime empire in the Mediterranean.

The Grand Tour was a cultural and educational journey taken by wealthy young men (and sometimes women) from Europe and North America in the 17th to early 19th centuries. Italy was a key destination, as it was considered the birthplace of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and was home to many of the world’s great works of art and architecture.

he Grand Tour was a customary journey through Europe that became popular in the 17th century and continued until the 19th century. It involved upper-class young men from Europe who were of sufficient means and rank, usually accompanied by a tutor or family member, and who had reached the age of 21. Italy was a key destination for the Grand Tourists, and the journey was seen as an educational rite of passage. The tradition flourished from around 1660 until the introduction of large-scale rail transport in the 1840s and was associated with a standard itinerary. Although it was mainly associated with the British nobility and wealthy landed gentry, wealthy young men from other Protestant Northern European nations also undertook similar trips, and from the second half of the 18th century, some South and North Americans also took part in the Grand Tour.

The Grand Tour was valued for its ability to expose young aristocrats to the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, as well as the refined and sophisticated society of Europe. It offered an opportunity to view specific works of art and hear certain types of music that were not easily accessible elsewhere. The tour could last for several months to several years, and it was common for travelers to be accompanied by a cicerone, a knowledgeable guide or tutor. The Grand Tour played a significant role in shaping the education and cultural development of Europe’s upper class during the 17th to early 19th centuries, and its influence continued to be felt in other parts of the world in subsequent years.

The Grand Tour had its roots in the long-standing tradition of pilgrimage to Rome, which had been popular among European clergy for centuries. In the early 17th century, Thomas Coryat’s travel book Coryat’s Crudities (1611) and the extensive tour of Italy taken by the Earl of Arundel and his family in 1613-14 served as early influences on the Grand Tour. The latter trip was significant because the Earl had Inigo Jones, a well-traveled masque designer, act as his guide.After the Peace of Münster was signed in 1648, larger numbers of tourists began to undertake their own Grand Tours. The term “Grand Tour” was first recorded in Richard Lassels’ book The Voyage of Italy, published posthumously in Paris in 1670 and in London thereafter. Lassels believed that travel furnished the “accomplished, consummate Traveller” with intellectual, social, ethical, and political benefits.

The Grand Tour provided a comprehensive education and the chance to acquire items that were not readily available, adding an element of accomplishment and prestige to the traveler. Upon returning home, Grand Tourists would bring back crates filled with books, works of art, scientific instruments, and cultural artifacts – from snuff boxes and paperweights to altars, fountains, and statuary – to be displayed in libraries, cabinets, gardens, drawing rooms, and galleries constructed specifically for that purpose. The symbols of the Grand Tour, particularly portraits of the traveler painted in continental settings, became the essential signs of sophistication, seriousness, and influence.

Naturally, this would maybe include locally tailored garments.

The dictionary “littre”, which was the first to define “touriste” in France, states

“Tourist means a person who travels abroad solely out of interest and unrelated to work. Usually a person who travels abroad with a large number of people in tow. It particularly refers to British nationals travelling in France, Italy and Switzerland.”

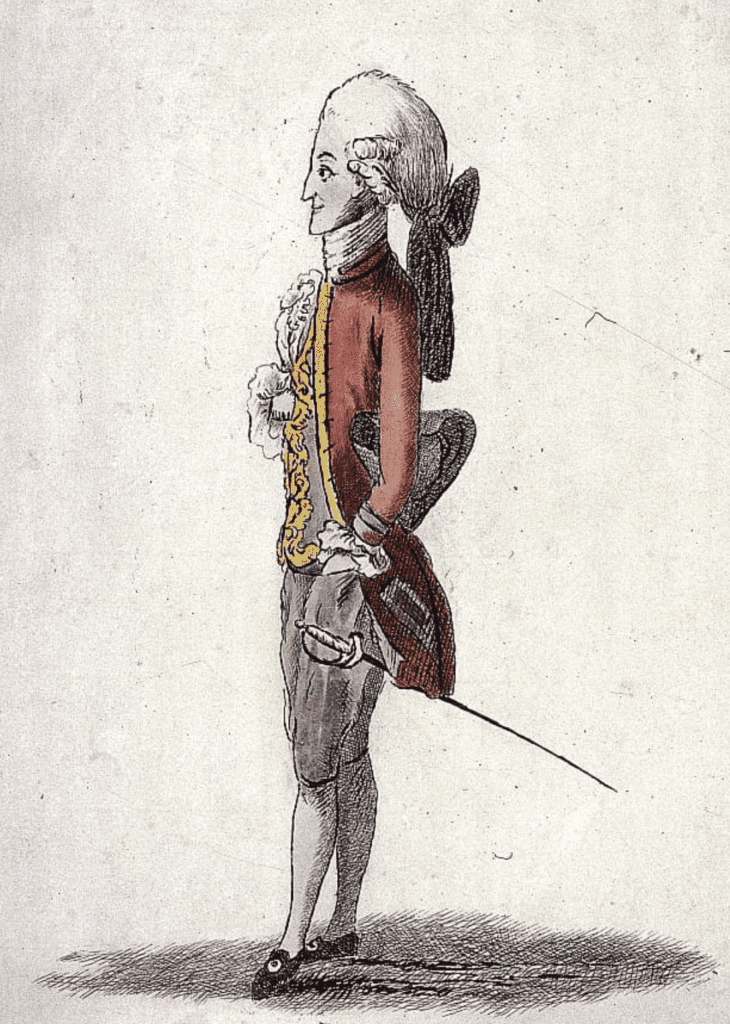

In the 18th century, it was customary for wealthy young British men to take a trip around Europe upon reaching adulthood, known as the Grand Tour, with Italy being a key destination. During their travels, many developed a taste for macaroni, a type of pasta that was little known in England at the time. As a result, they became known as members of the Macaroni Club and would refer to anything fashionable or à la mode as “very maccaroni”.

Macaroni was the forerunner of the dandies that followed, and the more masculine dandies were a reaction to the excesses of macaroni, a far cry from the softness that dandies have today.

In Oliver Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer (1773), a misunderstanding is discovered and young Marlow finds that he has been mistaken; he cries out, “So then, all’s out, and I have been damnably imposed on. O, confound my stupid head, I shall be laughed at over the whole town. I shall be stuck up in caricatura in all the print-shops. The Dullissimo Maccaroni. To mistake this house of all others for an inn, and my father’s old friend for an innkeeper!”

The song “Yankee Doodle” from the time of the American Revolutionary War mentions a man who “stuck a feather in his hat and called it macaroni.” Dr. Richard Shuckburgh was a British surgeon and also the author of the song’s lyrics; the joke which he was making was that the Yankees were naive and unsophisticated enough to believe that a feather in the hat was a sufficient mark of a macaroni. Whether or not these were alternative lyrics sung in the British army, they were enthusiastically taken up by the Americans themselves.

The French Revolution of 1789-1795 and the British Industrial Revolution of the 18th century reversed the status of the two countries. It was the British Empire that subsequently became the world’s dominant nation, and the fashion champions became also British.This aspect of the cultural spread of the British through their travels in Italy up to the 17th to 18th century should not be overlooked.

It can naturally be said about fashion.From this point onwards, fashion evolved towards a simpler, dandyism-driven fashion that emerged in Britain after the macaroni, rather than the flamboyant fashion of the royalty and aristocracy.

The aftermath of the two revolutions of the 18th century had a major impact on European society in the 19th century. The Industrial Revolution in Britain, with the advent of steam locomotives and new motive power, transformed the structure of previous industries and the economy was quickly steered towards capitalism.

Another revolution, the French Revolution, abolished absolute monarchy and recognised the rights of citizens.

The new Europe of the 19th century did not favour the elaborate Rococo decorations of the previous kings and aristocrats. The people of the new era preferred the classical style, which was the opposite of the times. The revival of past styles was triggered by the rediscovery of Herculaneum (now Ercolano) in southern Italy in 1738 and Pompeii in 1748.

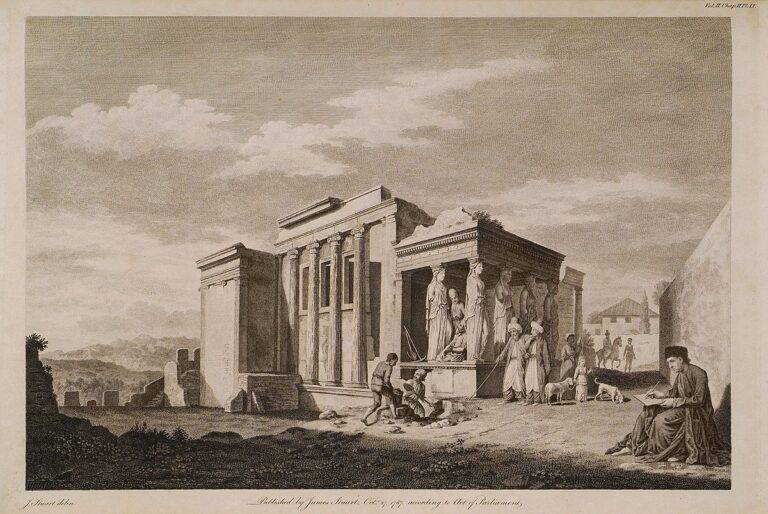

A View of the west end of the Temple of Minerva Polias, and of the Pandrosium – Stuart James & Revett Nicholas – 1787 Wikimedia Commons

It was not only the discoveries of Pompeii and other sites that heated up the archaeological boom: in 17562, British architects James Stewart and Nicholas Levett compiled the results of their two years of work on the sites in Athens and published Antiquities of Athens. ‘, was published. In Germany, the German art historian Johann Joachim Winkelmann published his Treatise on the Imitation of Greek Art (1755) and History of Ancient Art (1764).

Winkelmann taught that art should idealise nature (expressing the idea of beauty), which was achieved in ancient Greece, and that therefore our aim should be to imitate ancient Greece. The Romans had only imitated Greece; they believed that ancient Greece was the model of ‘noble simplicity and serene greatness’, and that the aim of art was to revive it. This was the theoretical underpinning of the new European style, neoclassicism.

Peace also prevailed in Europe, and the Grand Tour, in which children from wealthy British families visited the continent at the end of their studies, once again flourished during this period of safe travel.In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when transport links were much improved, young Britons travelled to the culturally advanced countries of France and Italy to see and learn about the early art and monuments, which led to the spread of neoclassicism to Britain.

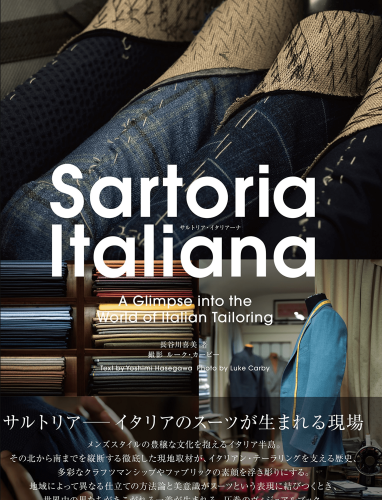

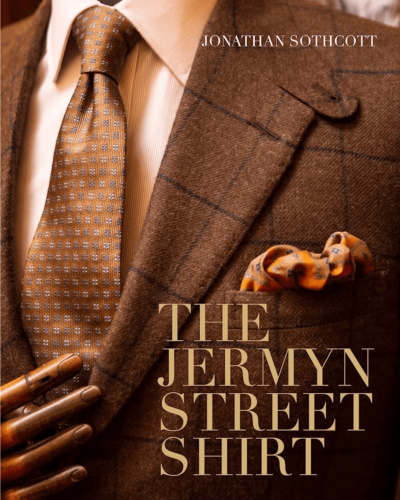

The Napoli dress shirt is famous for its high-quality and handmade craftsmanship, which is why it is often referred to as “Neapolitan tailoring.” The shirts are made by skilled artisans who have been trained in the art of tailoring and use traditional techniques passed down through generations.

One reason why the Napoli dress shirt is made by hand is to ensure that each shirt is made to the highest possible standard. Handmade shirts are meticulously crafted and attention is paid to every detail, from the quality of the fabric to the stitching and finishing touches.Another reason why the Napoli dress shirt is handmade is that it allows for a greater level of customization. Each shirt can be made to fit the individual wearer’s body shape and preferences, making it a truly personalized and unique garment.Finally, the handmade nature of the Napoli dress shirt reflects the pride and passion that the people of Naples have for their city and their traditions. The shirt is not just a piece of clothing, but a symbol of the craftsmanship and heritage that has made Naples famous around the world.(One aspect is that it is faster to sew by hand than by machine.)

The fabric used to make the Napoli dress shirt is also of the highest quality. The shirt is typically made from fine cotton or linen, which are both lightweight and breathable fabrics that are perfect for warm weather. The fabric is often sourced from the best mills in Italy and is carefully selected for its quality and texture. One of the unique features of the Napoli dress shirt is the use of different weaves and patterns in the fabric. For example, the shirt may feature a plain weave for the body of the shirt, but a more intricate pattern for the collar and cuffs. This attention to detail adds depth and character to the shirt and is another example of the skilled craftsmanship that goes into making each shirt by hand. Overall, the quality of the fabric used in the Napoli dress shirt is an important part of its reputation for excellence. The combination of fine fabrics, traditional techniques, and skilled craftsmanship make it a truly unique and highly sought-after garment.

I think it is hardly a coincidence that Naples’ most famous and legendary fashion sarto is ‘London House’ (founded in 1930/ Gennaro Rubinacci, Vincenzo Attolini, Mariano Rubinacci , Antonio Panico, Anna Matuozzo & Felice Bissone ).

I also want to really tell you. “See Naples and die.”I think that is the right word.