Byzantine dress underwent significant changes over the thousand-year history of the Empire, yet retained a conservative core. It stayed largely rooted in classical Greek traditions, with most stylistic evolutions occurring within the upper echelons of society. The Byzantines had a penchant for color and intricate patterns, producing and exporting richly decorated textiles, especially silk. For the upper classes, silk was woven and embroidered, while for the lower classes, resist-dyeing and printing were common. Garments often featured borders or trimmings and single stripes down the body or around the upper arm, indicating class or rank. The fashion preferences of the middle and upper classes were influenced by the latest trends at the Imperial Court. As in Western Europe during the Middle Ages, clothing was a significant expense for the poor, who likely wore the same clothes repeatedly until they were thoroughly worn out. For most women, clothing needed to accommodate the entire span of a pregnancy. Even among the wealthier classes, garments were “used until death and then reused,” with generous cuts to allow for this extended use.Byzantine dress not only served practical needs but also reflected social status, with the middle and upper classes following courtly fashion trends. The rich fabrics and elaborate designs of Byzantine textiles played a crucial role in the Empire’s economy and culture, symbolizing the wealth and sophistication of Byzantine society.

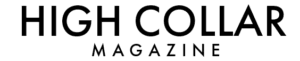

In the early stages of the Byzantine Empire, the traditional Roman toga was still used for very formal or official occasions. By the time of Justinian, this had been replaced by the tunica, or long chiton, worn by both sexes. The upper classes would wear additional garments over these, such as the dalmatica, a heavier and shorter type of tunica, also worn by both sexes but mainly by men, often with hems curving to a sharp point. The scaramangion, a Persian-origin riding coat opening down the front and usually reaching mid-thigh, was another notable garment, although emperors sometimes wore longer versions. Generally, except for military and riding attire, higher-status men and all women wore clothes that reached the ankles or nearly so. Wealthier women often wore a top layer of stola, made of luxurious brocade. All these garments, except the stola, could be belted or not. The terminology for these dresses is often confusing, and identifying specific items in historical records or images is rare, especially outside the court context.

Additionally, this is an image of authentic Byzantine clothing from the 5th to 7th century CE, housed in the collection of the Museum of Byzantine Culture in Thessaloniki.

The chlamys, a semicircular cloak fastened at the right shoulder, remained in use throughout the period. Its length varied from the hips to the ankles, much longer than the ancient Greek version, with the longer version also known as a paludamentum. Emperor Justinian, depicted in the Ravenna mosaics, wears a chlamys with a huge brooch. The senatorial class had a tablion, a lozenge-shaped colored panel across the chest or midriff, indicating rank through the color, type of embroidery, and jewels used. The position of the tablion rose over time, as seen in depictions from the late 4th and early 5th centuries. A paragauda or border of thick cloth, often with gold, was another rank indicator. Cloaks, especially for the military and ordinary people, were pinned on the right shoulder for ease of movement and access to a sword.

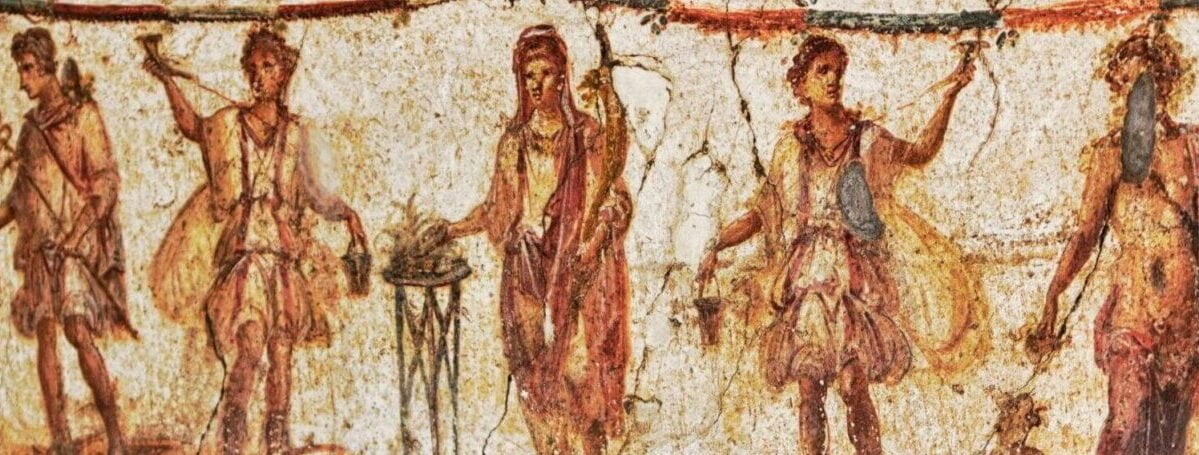

The most common surviving images from the Byzantine period do not accurately represent the actual dress worn during that time. Figures such as Christ (often depicted even as a baby), the Apostles, Saint Joseph, Saint John the Baptist, and others are frequently shown in a stylized “pseudo-Biblical dress.” This attire typically includes a large himation, a rectangular mantle wrapped around the body (similar to a toga), worn over a chiton or loose-sleeved tunic reaching the ankles, with sandals on the feet. Such costumes are rarely seen in secular contexts, likely to avoid confusion between secular and divine subjects. The Theotokos (Virgin Mary) is usually depicted wearing a maphorion, a shaped mantle with a hood and sometimes a hole at the neck, which probably resembles typical dress for widows and married women in public. The Virgin’s underdress may be visible, particularly at the sleeves. Old Testament prophets and other Biblical figures also follow these conventions. Aside from Christ and the Virgin, iconographic dress is typically white or muted in color in murals, mosaics, and manuscripts, but more brightly colored in icons. Other figures in Biblical scenes, especially unnamed ones, are often depicted wearing contemporary Byzantine clothing.

“I will not pass without a special word of praise of the Greeks. For at least fifteen hundred years and more they have not altered the style of their dress; their clothes are of the same fashion now as they were in the time indicated”

In the Byzantine Empire, modesty was paramount, and most women wore loose, shapeless clothes that covered them almost entirely and could accommodate a full pregnancy. Early Empire garments typically reached the ankles, had high round collars, and tight sleeves extending to the wrists. The fringes and cuffs were often decorated with embroidery and sometimes had bands around the upper arms. By the 10th and 11th centuries, dresses with flared sleeves, which became very full at the wrist, gained popularity but eventually disappeared; working women often tied up their sleeves. Court ladies’ dresses sometimes featured a V-collar. Belts were commonly worn, possibly with hooks to support the skirt, and were made more often of cloth than leather, with some featuring tasselled sashes. Neck openings were probably buttoned, a necessity for breast-feeding, although this is difficult to see in art and not well-documented. Until the 10th century, plain linen undergarments were not designed to be visible, but later, a standing collar started to show above the main dress. Women’s hair was covered by various head-cloths and veils, which were likely removed inside the home. Sometimes caps were worn under the veil, or the cloth was tied in a turban style, especially while working. By the 11th century, circular wrapping of veils became common, possibly sewn into a fixed position, and head-cloths or veils grew longer in the 11th and 12th centuries.

Scholars have a better understanding of Byzantine footwear due to archaeological finds in the drier parts of the Empire. A variety of footwear was used, including sandals, slippers, and mid-calf boots, with many decorated in various ways. Red, reserved for imperial male footwear, was actually the most common color for women’s shoes. Purses were rarely visible and seemed to be made of textile matching the dress, or perhaps tucked into the sash. Dancers wore special dresses with short sleeves or sleeveless designs, possibly with lighter sleeves underneath. These dresses had tight, wide belts, and their skirts featured flared and differently colored elements designed to rise during dances. Anna Komnene’s remark about her mother suggests that exposing the arm above the wrist was a particular focus of Byzantine modesty. Although some claim the Byzantines invented the face-veil, Byzantine art does not depict women with veiled faces, although veiled hair is common. It is assumed that Byzantine women outside court circles dressed conservatively in public and had limited movement outside the home, rarely appearing in art. Literary sources are not clear enough to distinguish between head-veils and face-veils. Additionally, early 3rd-century Christian writer Tertullian described pagan Arab women veiling their faces except for the eyes, indicating that some Middle Eastern women used face-veils long before Islam.

In the Byzantine Empire, as in Graeco-Roman times, purple was reserved for the royal family, while other colors indicated class and clerical or government rank. Lower-class people wore simple tunics but favored bright colors found in all Byzantine fashions. The races in the Hippodrome featured four teams: red, white, blue, and green. Supporters of these teams became political factions, taking sides on major theological and political issues, such as Arianism, Nestorianism, and Monophysitism, as well as on Imperial claimants who took sides. Huge riots, resulting in thousands of deaths, took place between these factions, especially in Constantinople from the 4th to the 6th centuries, with participants dressing in their respective colors. Similar political factions existed in medieval France, known as chaperons.

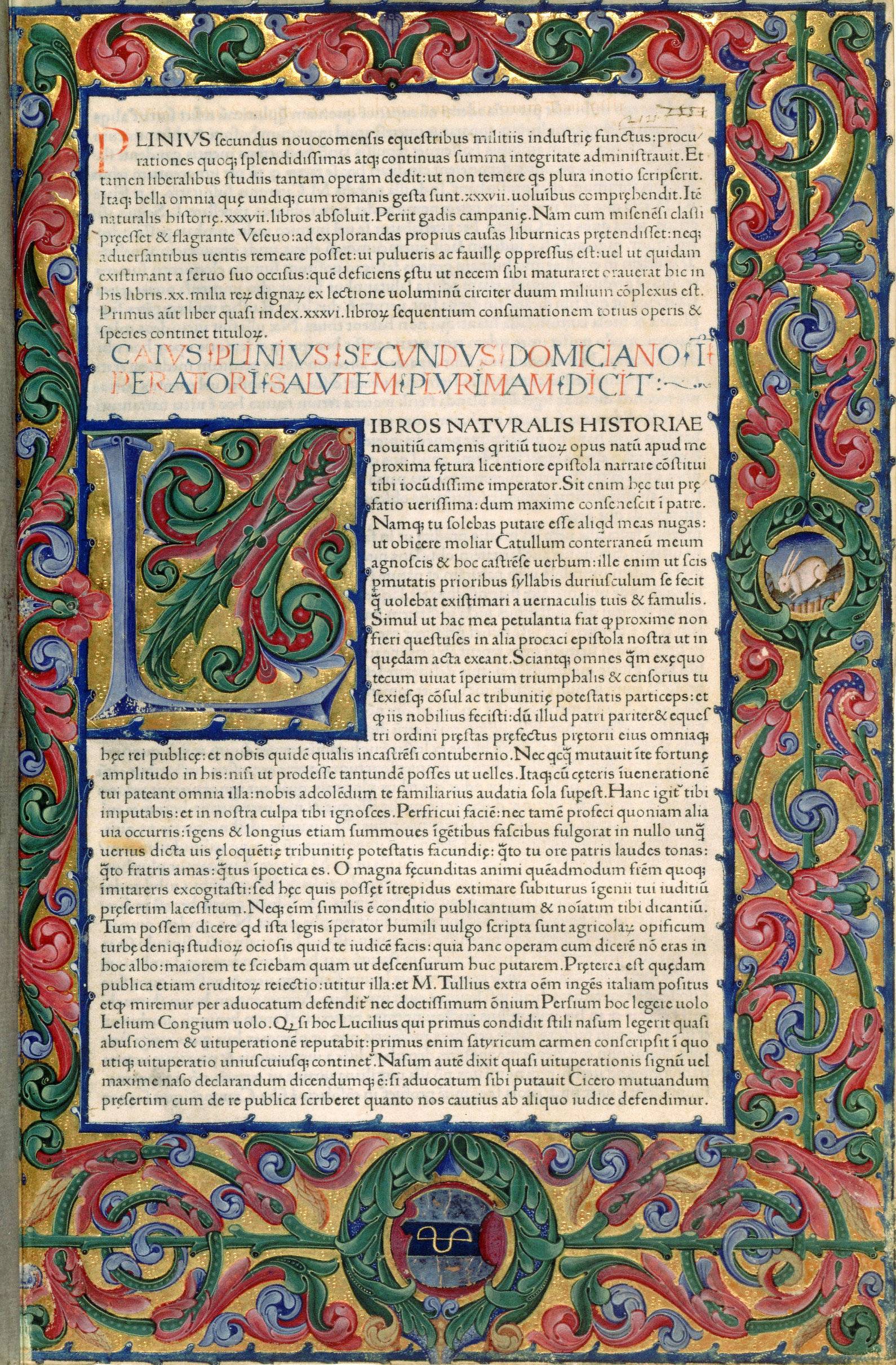

Patriarch Nicholas Mystikos baptizes Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos in 906.

13th century © wikipedia commons

The distinctive garments of the Emperors and Empresses included the crown and the heavily jewelled Imperial loros or pallium, which evolved from the trabea triumphalis, a ceremonial colored version of the Roman toga worn by Consuls. During Justinian I’s reign, the Consulship became part of imperial status, and the Emperor and Empress wore the loros as a quasi-ecclesiastical garment. This garment was also worn by the twelve most important officials and the imperial bodyguard, and by Archangels in icons, representing divine bodyguards. Its main purpose was ideological, symbolizing the deification of the monarch and his role as the sole legislator and administrator of the commonwealth. In practice, it was typically worn only a few times a year, such as on Easter Sunday, but it was frequently depicted in art.The male loros was a long strip that dropped straight down the front to below the waist, with the portion behind pulled round to the front and hung gracefully over the left arm. The female loros was similar at the front end, but the back end was wider and tucked under a belt after being pulled through to the front again. Both male and female versions changed style during the middle Byzantine period, with the female version later reverting to the new male style. Apart from jewels and embroidery, small enamelled plaques were sewn into the clothes. The dress of Manuel I Comnenus was described as resembling a meadow covered with flowers. Generally, the sleeves were closely fitted to the arm, and the outer dress extended to the ankles. The sleeves of empresses became extremely wide in the later period.

The royal daily robe was a simpler and more idealized regalia of various Hellenistic kings, depicted in frescoes and miniatures. This featured the emperor in a simple “chiton” robe, a “chlamys” of various sizes, a royal diadem, and the imperial boots Tzangion. Elaborate examples are evidenced in imperial works such as the Paris Psalter or the David Plates, idealizing the concept of philanthropy and beneficence as the main roles of the perfect Hellenistic and Byzantine monarch.The superhumeral, worn throughout Byzantine history, was the imperial decorative collar, often part of the loros. It was copied by upper-class women and made of cloth of gold or similar material, studded with gems and heavily embroidered. The decoration was generally divided into compartments by vertical lines on the collar, with edges done in pearls of varying sizes in up to three rows. Occasionally, drop pearls were placed at intervals to add richness. The collar came over the collarbone to cover a portion of the upper chest.

The Imperial Regalia of the Holy Roman Emperors, kept in the Schatzkammer in Vienna, contains a full set of outer garments made in the 12th century in essentially Byzantine style at the Byzantine-founded workshops in Palermo. These garments give a good idea of the lavishness of Imperial ceremonial clothing, including a cloak, “alb”, dalmatic, stockings, slippers, and gloves. The loros is Italian and later. Each element of the design on the cloak is outlined in pearls and embroidered in gold. Especially in the early and later periods (before 600 and after 1000), Emperors may be depicted in military dress, with gold breastplates, red boots, and a crown. Crowns had pendilia and became closed on top during the 12th century.

c958 Replica of a miniature of Emperor Basil II in triumphal garb, exemplifying the Imperial Crown handed down by Angels. Replica of the Psalter of Basil II (Psalter of Venice), BNM, Ms. gr. 17, fol. 3r

© wikipedia commons

Manuscript illumination of Emperor Nicephorus III Botaniates (1078-81) flanked by St John Chrysostomos and the Archangel Michael © wikipedia commons

Miniature of the sebastokrator Constantine Palaiologos and his wife Irene, from the so-called Lincoln Typicon, c. 1350 © wikipedia commons

Manuel II Palaiologos, Byzantine Emperor from 1391 until his death in 1425.

© wikipedia commons

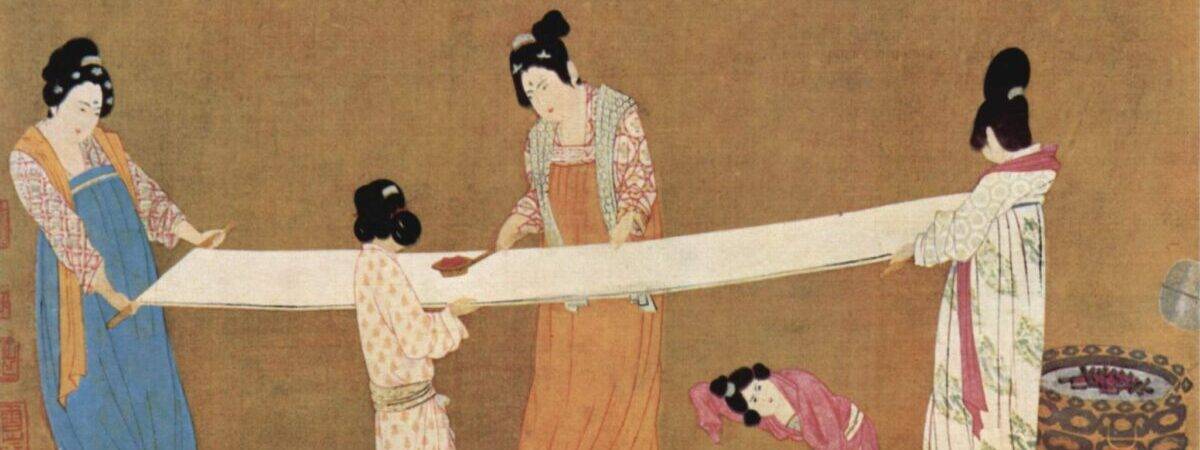

In the Byzantine Empire, large Imperial workshops, much like those in China, were dedicated to the production of textiles and other arts like mosaics. These workshops, primarily based in Constantinople, were pivotal in setting fashion and technical trends. Their products were often used as diplomatic gifts and distributed to favored Byzantines. For instance, in the late 10th century, the Emperor sent gold and fabrics to a Russian ruler to prevent an attack on the Empire. Most surviving examples of Byzantine textiles are not clothing but large woven or embroidered pieces. Before the Byzantine Iconoclasm, these often featured religious scenes, such as the Annunciation, in multiple panels across large pieces of cloth. During the Iconoclasm, figural scenes were mostly replaced by patterns and animal designs, except in church vestments. Some examples show large designs used for clothing, like the enormous embroidered lions on the Coronation cloak of Roger II in Vienna, produced in Palermo around 1134.Saint Asterius of Amasia, in a 5th-century sermon, provides details of the imagery on the clothes of the rich, which he strongly condemned. He described garments adorned with images of lions, leopards, bears, bulls, dogs, nature scenes, and even gospel stories.Both Christian and pagan examples, mostly embroidered panels sewn into simpler cloth, have been preserved in Egyptian graves, although they are mostly iconic portraits rather than the narrative scenes described by Asterius. The portrait of Caesar Constantius Gallus in the Chronography of 354 shows several figurative panels on his clothes.

Early decorated cloth was mostly embroidered in wool on a linen base. Linen was more common than cotton throughout the period. Raw silk yarn was initially imported from China. The timing and place of the first weaving of silk in the Near Eastern world is debated, with Egypt, Persia, Syria, and Constantinople all proposed for dates in the 4th and 5th centuries. Byzantine textile decoration shows significant Persian influence and little direct Chinese influence. According to legend, agents of Justinian I bribed two Buddhist monks from Khotan around 552 to learn the secret of cultivating silk, although much silk continued to be imported from China.

Resist dyeing was common from the late Roman period for those outside the court. Woodblock printing dates to at least the 6th century, possibly earlier, functioning as a cheaper alternative to woven and embroidered materials. Apart from Egyptian burial cloths, fewer cheap fabrics have survived compared to expensive ones. Depicting patterned fabric in paint or mosaic is a difficult task, often impossible in small miniatures, so the artistic record probably under-reports the use of patterned cloth.

ビザンツ帝国の初期段階では、伝統的なローマのトガが非常に正式な場や公式の場でまだ使用されていました。ユスティニアヌスの時代になると、これは長いキトン(チュニカ)に取って代わられ、男女ともに着用されました。上流階級はこれらの上にダルマティカのような他の衣服を着ていました。ダルマティカはより重く短いタイプのチュニカで、これも男女ともに着用されましたが、主に男性が着用し、裾は鋭い点に向かってカーブすることがよくありました。スカラマンギオンはペルシャ起源の乗馬用コートで、前が開いていて通常は太ももの中ほどまでの長さでしたが、皇帝が着用する場合にはより長いものになることもありました。一般的に、高位の男性やすべての女性は足首まで、またはそれに近い長さの服を着ていました。裕福な女性はしばしば豪華なブロケードで作られたストラをトップレイヤーとして着用しました。これらの衣服はすべて、ストラを除いて、ベルトで締めることもありました。これらの衣服の用語はしばしば混乱を招き、特に宮廷外では、歴史的記録や画像で特定のアイテムを識別することはまれです。

クロミスは、右肩に留められた半円形のマントで、この時代を通じて使用され続けました。その長さは腰から足首までさまざまで、古代ギリシャで一般的に着用されたバージョンよりもはるかに長く、長いバージョンはパルダメントゥムとも呼ばれました。ラヴェンナのモザイク画に描かれたユスティニアヌス皇帝は、大きなブローチでクロミスを留めています。元老院階級の男性は、胸部または腹部にタブリオンという菱形のカラーパネルを持ち、色や刺繍の種類、宝石を使用して着用者の階級を示しました。4世紀後半から5世紀初頭の描写では、タブリオンの位置が徐々に高くなっていることがわかります。厚手の布でできた縁取り、しばしば金を含むパラガウダも階級の指標でした。軍人や一般市民は特に、動きやすさと剣へのアクセスのために、右肩にマントを留めました。

レギンスやホース(ストッキング)はしばしば着用されましたが、富裕層の描写にはあまり見られず、ヨーロッパやペルシャの野蛮人と関連づけられていました。基本的な衣服は貧しい人々にとって驚くほど高価でした。一部の手動労働者、おそらく奴隷は、少なくとも夏には、肩と腕の下で縫い合わされた二つの長方形の基本的なローマのスリップコスチュームを着続けました。他の労働者は、活動中に動きやすさのためにチュニックの両側を腰まで縛っていることが描かれています。

ビザンツ時代から現存する一般的な画像は、当時実際に着用されていた服装を正確に表しているわけではありません。キリスト(幼児として描かれることも多い)、使徒たち、聖ヨセフ、洗礼者ヨハネなどの人物は、しばしば形式化された「擬似聖書的な服装」を着ていると描かれています。この服装には、大きなヒマティオン(体に巻きつける長方形のマント、トガに似ている)、足首までの長さのチュニックやゆったりとした袖のキトン、サンダルが含まれます。このような衣装は世俗的な文脈ではほとんど見られませんが、これはおそらく世俗的なものと神聖なものを混同しないようにするためです。テオトコス(聖母マリア)は、フード付きの形作られたマントであるマフォリオンを着ていると描かれることが多く、時には首の部分に穴が開いています。これは、おそらく未亡人や公共の場での既婚女性の典型的な服装に近いでしょう。聖母の下着は特に袖の部分で見えることがあります。旧約聖書の預言者やその他の聖書の人物もこれらの服装規定に従います。キリストと聖母を除いて、アイコンの服装は壁画、モザイク画、写本では一般的に白や控えめな色ですが、アイコンではより鮮やかな色で描かれます。聖書の場面に登場する他の人物、特に名前のない人物は、多くの場合、当時のビザンツの服装を着ていると描かれています。

ビザンツ帝国では、慎み深さが非常に重要視されており、ほとんどの女性はゆったりとした形のない服を着て、ほぼ全身を覆い、妊娠期間中の体型変化にも対応できるようにしていました。初期の帝国の基本的な衣装は足首までの長さで、高い丸襟と手首までのタイトな袖が特徴でした。縁や袖口は刺繍で装飾されていることが多く、上腕部にはバンドがあることもありました。10世紀から11世紀には、袖が広がり、手首の部分が非常に広がるドレスが流行しましたが、やがて廃れました。働く女性は袖を縛っていることがよくありました。宮廷の女性の服装にはV字の襟があることもありました。ベルトは通常着用され、スカートを支えるためのフックが付いていることもあり、布製が多く、時には房のついたサッシュも見られました。首の開口部はボタンで留められていたと考えられますが、これは芸術作品では見えにくく、文献でも明確に記述されていませんが、授乳のために必要だったはずです。10世紀までは、シンプルなリネンの下着は見えるようにはデザインされていませんでしたが、この時点からメインドレスの上に立ち襟が見えるようになりました。女性の髪はさまざまなヘッドクロスやベールで覆われており、おそらく家の中では取り外されていました。時にはベールの下にキャップをかぶったり、布をターバンのように結んだりしました。

ビザンツ帝国において、衣服の色は非常に象徴的であり、厳しく規制されていました。紫色は王族専用であり、皇帝の権力と地位を象徴していました。この色の使用は王族以外には禁じられており、その重要性が際立っていました。その他の色は、階級、聖職者や政府のランクに関連する異なる意味を持っていました。例えば、赤はしばしば高位の官僚や聖職者と関連付けられていました。下層階級の人々はシンプルなチュニックを着ていましたが、明るい色を好む傾向があり、ビザンツの色彩への愛好が反映されていました。ヒッポドロームでの戦車競走の派閥も特定の色を使用してチームを表していました:赤、白、青、緑です。これらのチームの支持者はしばしば政治的派閥となり、アリウス派、ネストリウス派、単性論などの主要な神学的および政治的問題に関して立場を取りました。4世紀から6世紀にかけて、これらの派閥の支持者の色が目立ち、コンスタンティノープルでの大規模な暴動を引き起こし、数千人が死亡することもありました。これらの色を使った派閥は、中世フランスの「シャペロン」と呼ばれる政治グループの先駆けであり、特定の色で自分たちを識別していました。

皇帝と皇后の特徴的な衣装には、王冠と宝石がちりばめられた帝国のロロスまたはパリウムが含まれました。これは、ローマの執政官が着用していた儀式用のカラーのトガであるトラベア・トリウンファリスから進化したものです。ユスティニアヌス1世の治世中に、執政官職は皇帝の地位の一部となり、皇帝と皇后はロロスを準宗教的な衣装として着用しました。この衣装は、最も重要な12人の高官と帝国の護衛隊、およびアイコンの中の大天使たちにも着用され、神聖な護衛隊として見なされました。その主な目的は、君主の神格化と彼の立法者および国家の管理者としての役割を象徴するものでした。実際には、イースターの日曜日など、年に数回しか着用されませんでしたが、芸術作品には頻繁に描かれていました。男性用のロロスは、前面に真っ直ぐに垂れ下がり、腰の下まで伸び、後ろの部分は前面に引き寄せられて左腕に優雅にかけられました。女性用のロロスも前面は同様ですが、後ろの部分は広く、ベルトの下に引き寄せられて前面に再度引き寄せられました。男女両方のバージョンは中期ビザンティン時代にスタイルが変わり、女性用は後に新しい男性用スタイルに戻りました。宝石や刺繍の他に、小さなエナメルのプラークが衣服に縫い付けられていました。マヌエル1世コムネヌスの衣装は、花で覆われた牧草地のようだと表現されました。一般的に、袖は腕にぴったりとフィットし、外側のドレスは足首まで伸びていました。後期には皇后の袖が非常に広がりました。王室の日常のローブは、さまざまなヘレニズム王のシンプルで理想化されたレガリアであり、フレスコ画やミニチュアに描かれています。これには、シンプルな「キトン」ローブ、さまざまなサイズの「クラミス」、王冠、帝国のブーツであるツァンギオンが含まれていました。パリ・プサルターやデヴィッド・プレートのような帝国の作品に見られる華麗な例は、完璧なヘレニズムとビザンティンの君主の主要な役割として、慈善と恩恵の概念を理想化していました。

スーパーヒューメラルは、ビザンティンの歴史を通じて着用された帝国の装飾的な襟であり、しばしばロロスの一部を形成していました。これは、少なくとも上流階級の女性によって模倣され、金の布または同様の素材で作られ、宝石で飾られ、豪華に刺繍されました。装飾は一般的に襟の縦線によって区画に分けられ、縁は最大三列のさまざまなサイズの真珠で装飾されました。時折、真珠が一定間隔で配置され、豪華さが増しました。この襟は鎖骨を覆い、上胸部の一部を覆うように作られました。ウィーンのシュッツカンマーに保管されている神聖ローマ皇帝の帝国レガリアには、12世紀にパレルモのビザンティン創設の工房で作られた、基本的にビザンティンスタイルの外衣の完全なセットが含まれています。これらの衣装は、帝国の儀式的な服装の豪華さをよく示しており、クローク、「アルブ」、ダルマティック、ストッキング、スリッパ、グローブが含まれています。ロロスは後にイタリア製です。クロークのデザインの各要素は真珠で縁取られ、金糸で刺繍されています。特に初期と後期(600年以前と1000年以降)には、皇帝は軍装姿で描かれることが多く、金の胸当て、赤いブーツ、王冠を身に着けていました。王冠にはペンディリアがあり、12世紀には上部が閉じられました。

ビザンツ帝国では、中国と同様に、大規模な帝国の工房が織物やモザイクなどの他の芸術に専念していました。これらの工房は主にコンスタンティノープルに拠点を置き、ファッションと技術のトレンドを設定する上で重要な役割を果たしました。これらの製品はしばしば外交の贈り物として使用され、ビザンツの有力者に配布されました。例えば、10世紀後半には、皇帝が金と織物をロシアの統治者に送り、帝国への攻撃を防ごうとしました。

現存するビザンツの織物の多くは衣服ではなく、大規模な織物や刺繍作品です。ビザンツのイコン崇拝破壊運動(アイコノクラスム)以前は、受胎告知などの宗教的な場面を描いたものが多く、大きな布に複数のパネルで表現されていました。アイコノクラスムの時期には、図像的な場面は主にパターンや動物のデザインに置き換えられ、教会の祭服を除いてほとんど再現されませんでした。一部の例では、1134年頃にパレルモで製作されたロジャー2世の戴冠マントに見られるような、大きな刺繍のデザインが衣服に使用されていました。5世紀末のアマシアのアステリウス聖人の説教には、富裕層の衣服に描かれたイメージの詳細が記されています。彼は、ライオン、ヒョウ、クマ、ウシ、イヌ、自然の風景、さらには福音書の物語が描かれた衣服を批判しました。キリスト教徒と異教徒の両方の例は、主に刺繍されたパネルがシンプルな布に縫い付けられたものであり、エジプトの墓で保存されていますが、アステリウスが述べたような物語の場面ではなく、主にアイコン的なポートレートです。354年の『年代記』に描かれたカエサル・コンスタンティウス・ガルスの肖像には、彼の衣服にいくつかの図像パネルが描かれています。

初期の装飾された布は主にリネンベースにウールで刺繍されていました。リネンは綿よりも一般的でした。生絹の糸は最初は中国から輸入されました。絹が近東世界で初めて織られた時期と場所は議論の余地があり、エジプト、ペルシア、シリア、コンスタンティノープルが4世紀と5世紀に提案されています。ビザンツの織物装飾はペルシアの影響が大きく、中国からの直接の影響はほとんどありません。伝説によれば、ユスティニアヌス1世のエージェントが552年頃にホータンの仏教僧に賄賂を渡して、絹の栽培の秘密を学んだとされていますが、多くの絹は中国からの輸入が続きました。抵抗染めは、宮廷外の人々のためにローマ後期から一般的に行われていました。木版印刷は少なくとも6世紀には行われており、織物や刺繍された高価な素材の代替として機能しました。エジプトの埋葬布を除けば、安価な織物よりも高価な織物が多く残っています。パターンのある布を絵画やモザイクで描くのは非常に難しい作業であり、小さなミニチュアではほぼ不可能です。そのため、芸術作品はパターンのある布の使用を過小評価している可能性があります。