TEXTILE

CANTON FLANNEL / CIVIL WAR

OCTOBER – 2023 20 MINS READ

Flannel is of course the most developed fabric in Europe, but the culture of producing textiles itself has developed all over the world. Textiles were raised all over the world because they were warm wear and made ideal underwear. During the American Civil War, flannel was widely used. After the devastation of Europe after World War I, many Asian (Chinese and Japanese) textiles were exported to the booming United States. In this issue, we will study Cantonese flannel, which was regarded as the best of the best.

フランネルは、もちろんヨーロッパで最も発展した織物ですが、織物を生産する文化そのものは世界中で発展してきました。フランネルは暖かく、理想的な防寒着や下着となるため、世界中で愛用されてきました。アメリカの南北戦争では、フランネルシャツが広く使用されました。第一次世界大戦後のヨーロッパの荒廃の後、多くのアジア(中国や日本)の織物が好景気のアメリカに輸出されました。今回はその中でも最高級とされた「広東フランネル」について、学んでみましょう。

AMERICAN CIVIL WAR

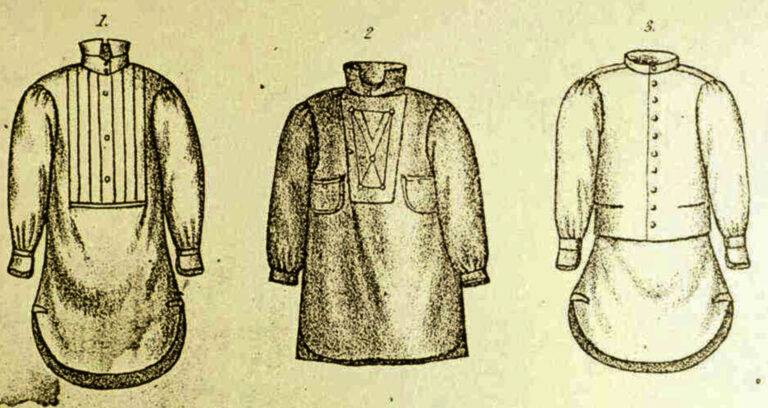

The shirt issued by the U.S. government before and during the war was made of white domet flannel, a cotton and wool material. This pullover Shirt was issued in a single size, with a single button at the neck and one at each cuff. The design made for ease of construction and certainly made requisition a simple matter of ordering enough to fill the need without regard to fit. During 1863, gray material was ordered as a secondary standard. From that date on, both were distributed on about an equal basis. Union soldiers are seen in numerous photographs in various styles and patterns of civilian shirts that were privately obtained; however, the use of civilian clothing by soldiers was discouraged and at times strictly for- bidden.the large purchase of jackets and orther items from Petter Tait in 1864. were described in the original letter sent to the seretary of war as “strong gray flannel”.

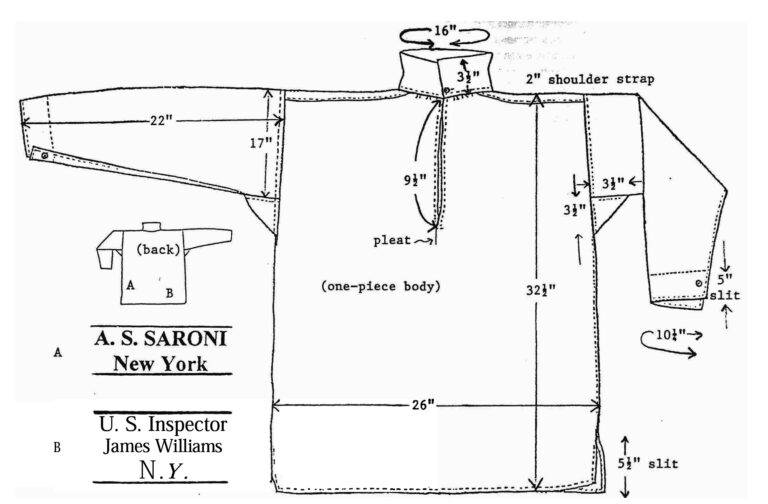

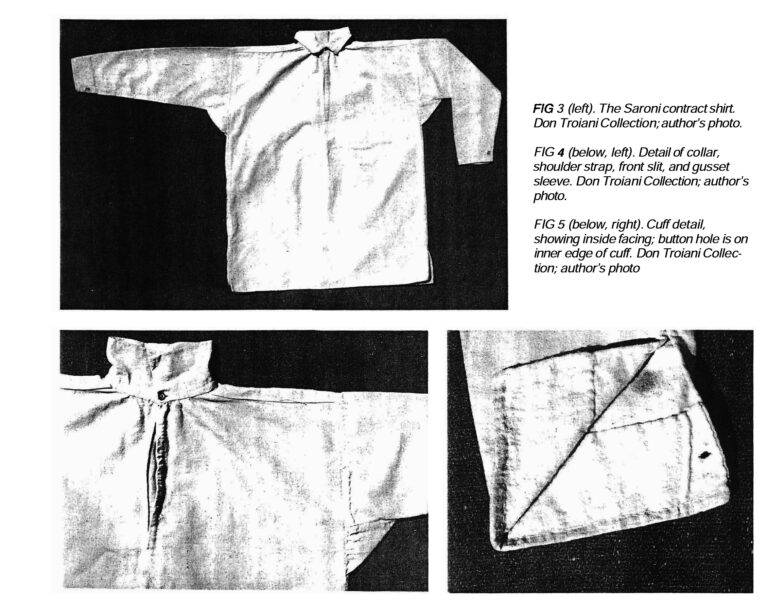

Army contract domet flannel shirt made by A. S. Saroni as part of his ontact for 50,000 shirts in December 1861. All of these shir were completely fabricated by hand, each requiring up to 2,000 stitches. A capable seamstress could make about three in a twelve- hour day, earning approximately 7 cents each. The contractors often made the overworked seamstresses furnish their own thread TROIANI COLLECTION

南北戦争の前後および戦争中にアメリカ政府から支給されたシャツは、綿と羊毛の混紡物である白いドメフランネルで作られていました。このプルオーバーシャツは、首元にボタン1つ、袖口にボタン1つずつが付いており、1サイズのみで支給されました。このデザインは、製造を容易にするためのものであり、必要量を確保するために適合を考慮せずに注文するだけでよかったのです。1863年には、セカンダリストンダードとしてグレーの素材が注文されました。それ以降、両方の素材がほぼ同等に配布されました。ユニオン軍の兵士たちは、民間人が私的に入手したさまざまなスタイルやパターンの民間シャツを着ている写真が数多く残されていますが、兵士による民間服の使用は推奨されず、時には厳しく禁じられていました。ペッター・テイトから1864年に大量購入したジャケットやその他のアイテムは、戦争省長官に送られた最初の手紙の中で「丈夫なグレーのフランネル」と説明されています。

1861年12月に50,000枚のシャツの契約を結んだA.S.サロニが製作した、陸軍契約のドメフランネルシャツ。これらのシャツはすべて手作業で作られており、1枚あたり最大2,000針が必要です。熟練した縫い子は12時間で約3枚作ることができ、1枚あたり約7セントの収入を得ていました。下請け業者は、過労の縫い子に自分の糸を使わせることが多かった。

AMONG the relatively sparse quantity of Union soldiers’ clothing that has somehow survived the one hundred and . .. . thirty years since the end of the Civil War, undergarments (including shirts, drawers and socks), are the rarest of all-for . . . . reasons obvious to anyone who has given the matter even cursory thought. Undergarments(F1G 1)were the most quickly used-up articles of the common soldiers’ limited wardrobe. The routine exertions of marching under loads, digging I trenches, felling trees, chopping and hauling firewood, build- . , ing huts, and countless other sweaty tasks that made up the soldier’s exhausting day visited themselves first, and worst, . .-. .? on the humble undergarment. Shirts, drawers, and socks all functioned as a highly absorbent, lightweight buffer between the soldierproperand the heavywool, jean clothsand satinettes that comprised the soldiers’ outer uniform. They were soaked through with perspiration, grossly stained by soldiers’ grime, infested by lice, and by necessity or soldierly indifference, .they were often worn until worn-out or rendered so repulsive that a new, or at least fresher, replacement became imperative. In the field, opportunities for laundering were infrequent and far from satisfactory; a quick rinse in a muddy creek or stint in a boiling camp kettle often had to suffice. Cheap materials, hurried making, hard wear, and the chronic rancidity of the typical undergarment contributed to an exceptionally high attrition rate for this echelon of soldiers’ clothing. Those soldiers who were inclined to save some of their garb and gear as mementos of their war experiences seldom retained their shirts, drawers, or socks. Such anonymous and undistin- guished items were generally omitted from a veteran’s notions of resonant keepsakes; they were seldom retained as an agent of memory. By contrast, soldiers7 caps or uniform coats conveyed a distinct military identity evident in fabric, cut, and fittings; they held immediate appeal as war relics, and as a consequence were the most commonly saved of uniform components.

南北戦争が終結して130年以上経ちますが、北軍兵士の衣服は比較的少量しか残されていません。その中でも、アンダーウェア(シャツ、ズボン、靴下など)は最も希少です。これは、容易にご想像いただける理由によるものです。アンダーウェアは、兵士の限られたワードローブの中で最も消耗品でした。

兵士の日常的な重労働、すなわち重荷を背負って行軍し、塹壕を掘り、木を切り倒し、薪を運び、小屋を建てるなどの作業は、まず第一にこのささやかなアンダーウェアに大きな負担をかけました。シャツ、ズボン、靴下はすべて、兵士本人と、兵士の外側の制服を構成していた重いウール、ジーンズ、サティネットの間に、吸湿性に優れた軽量な緩衝材として機能しました。

これらのアンダーウェアは、汗でびっしょりになり、兵士の汚れでひどく汚れており、シラミがつきまとい、必要性または兵士の無関心さから、しばしば履きつぶされたり、嫌悪感を抱くほどに汚くなるまで着用されました。戦場での洗濯の機会は少なく、十分とは言えませんでした。泥だらけの小川でさっとすすいだり、煮えたぎるキャンプの釜で煮たりしなければならないことが多かったです。

安価な素材、粗雑な作り、酷使、そして典型的なアンダーウェアの慢性的な悪臭は、兵士の衣服のこの階級の摩耗率を非常に高めました。戦争体験の記念品として自分の服装や装備の一部をとっておく傾向のある兵士たちは、めったにシャツ、ズボン、靴下をとっておかなかったようです。このような無名で目立たないアイテムは、一般的に退役軍人の思い出に残る品々から除外されていました。それらは、記憶を呼び起こすための手段としてめったに保存されませんでした。それとは対照的に、兵士の帽子や軍服は、生地、カット、フィット感に表れる明確な軍事的アイデンティティを伝えていました。それらは戦争の遺物としてすぐに魅力を感じられるものであり、結果として最もよく保存された軍服の構成要素となりました。

FIG I. Shirt, drawers and stockings, old pattern, prior to 1872. The shirts, drawers and stockings are worst of all, past comment and a scarecrow would play high dandy to any man dressed in them alone, while the rebels would take him for the Yankee devil himself. The prime trouble is that the clothing is all ‘theoretical regulation’, while the soldiers had practical, and very many different styles of fathers.” Lt. S. Millett Thompson, 13th New Hampshire Volunteers. Quartermaster Department Clothing Photographs, ca. 1872. Courtesy Smithsonian Institution (#50 159).

(図1)は、1872年以前の旧式シャツ、ズボン、ストッキングを示しています。シャツ、ズボン、ストッキングはどれもひどいもので、コメントに耐えられないほどです。これらだけで身を包んだ男は、かかしでも立派なダンディに扮装したように見えるでしょう。反乱軍は彼をヤンキーの悪魔そのものだと思ってしまうでしょう。最大の理由は、服装がすべて「理論上の規定」であり、兵士には実用的な、そして非常に多くの異なるスタイルがあったからです。S. ミレット・トンプソン中尉、第13ニューハンプシャー連隊。兵站部被服写真、1872年頃。スミソニアン協会提供

There were, of course, exceptions. Recalling in postwar memoirs his “war fever” enlistment and transition from a schoolboy into a soldier, drummer Harry Kiefer of the 150th Pennsylvania Volunteers wrote of his unit’s first clothing issue at Camp Curtin, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in the fall of 1862: Aswe now belonged to Uncle Sam, it was to be expected that he would nextproceed toclothe us… Each rnanreceivedapairofpantal~ns~acoat, cap, overcoat, shoes, blanket and underwear, of which latter the shirt was-well, a revelation to most of us both as to size, and shape and material. It was so rough, that no living mortal, probably, could wear it, except perhaps one who wished to do penance by wearing a hair shirt. Mine was promptly sent home along with my citizen’s clothes, with the request that it be kept as a sort of heir-loom in the family for future generations to wonder at.’

当然ながら、例外もありました。戦後の回想録で、彼の「戦争熱」による入隊と学童から兵士への変化を振り返った、ペンシルベニア州第150連隊のドラマーであるハリー・キーファーは、1862年秋、ペンシルベニア州ハリスバーグのキャンプ・カーティンで部隊に初めて衣類が支給されたときのことを書いています。「私たちは今、アンクル・サムに属しているので、彼が次に私たちに衣服を支給してくれることは当然であると考えられました。各兵士には、ズボン、コート、帽子、オーバーコート、靴、毛布、そして下着が支給されました。この下着のうち、シャツは、サイズ、形、素材のいずれにおいても、私たちのほとんどにとって、一種の啓示でした。それは非常に粗く、おそらく、髪衣を着て苦行を行いたい人を除いては、生きている人間は誰も着ることができなかったでしょう。私のシャツは、市民服と一緒にすぐに家に送り返し、将来の世代が不思議に思うために、家族の中に一種の家宝として保管してほしいと依頼しました。」キーファーのシャツは、おそらく、北軍兵士に支給されたアンダーウェアの品質の悪さの典型的な例であったのでしょう。兵士たちは、このような粗悪な衣服を着なければならなかったため、非常に不快で不衛生な環境に置かれていました。

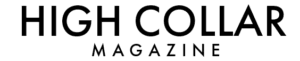

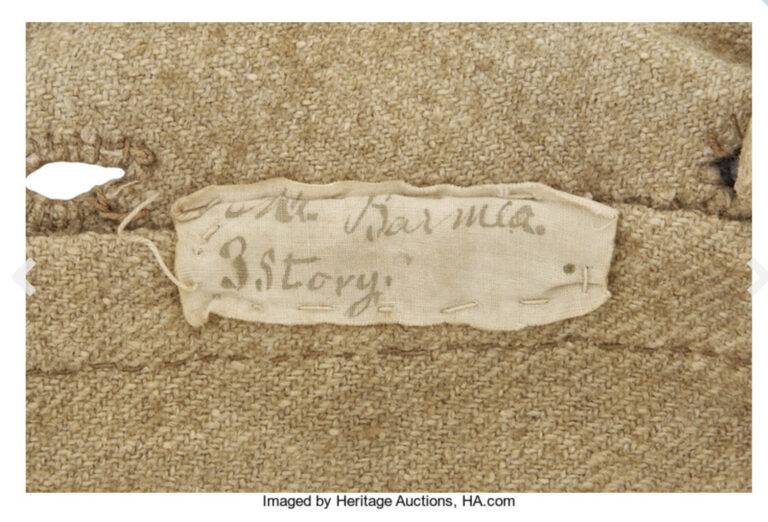

Bullet Struck Shirt Worn by Michigan Artilleryman. This hand sewn, medium weight, coarse wool pullover shirt has the classic look of the Civil War garment seen in countless soldier images, with a low turnover collar and three-button fly front. There is a large breast pocket closed with a single button and cuffs which also close with a single button (one missing). All buttons are made of bone. Inside the shirt opening is a small white linen label inked with “M Barnea/ 3 Story.” In the back, right side of the shirt is a hole near which appears to be some dark staining. The shirt is accompanied by an old handwritten note on the back of a business trade card that states “Blouse lining/Showing where ball entered/when wounded at Chickasaw/Bayou rear of Vicksburg/Miss/M. Barnea.” The card shows signs of having been pinned to this shirt at one time. Pvt. Monroe Barnea enlisted in December, 1861 in Battery G, 1st Michigan Light Artillery. With the shirt are his standard G.A.R. medal and a souvenir program from a 1912 encampment in South Bend, Indiana. In the early days of the Vicksburg campaign Barnea was struck in the side by a minie ball while serving his piece at Chickasaw Bayou, Miss., December 27, 1862. He underwent a long recovery and did not rejoin his unit until April, 1864, mustering out with the battery in January, 1865. While soldiers treasured possessions that had been “touched by fire”,” few bullet-struck articles of clothing are in existence today. This is a significant rarity with a great history.

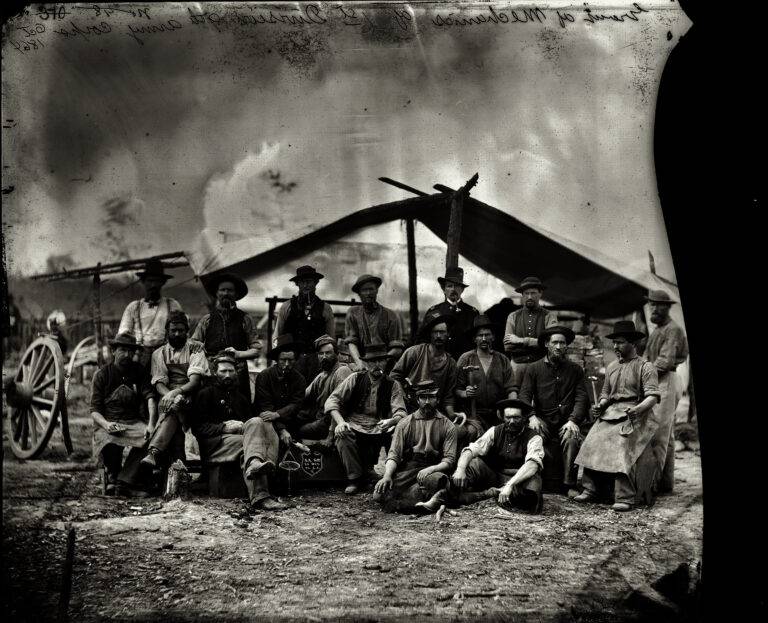

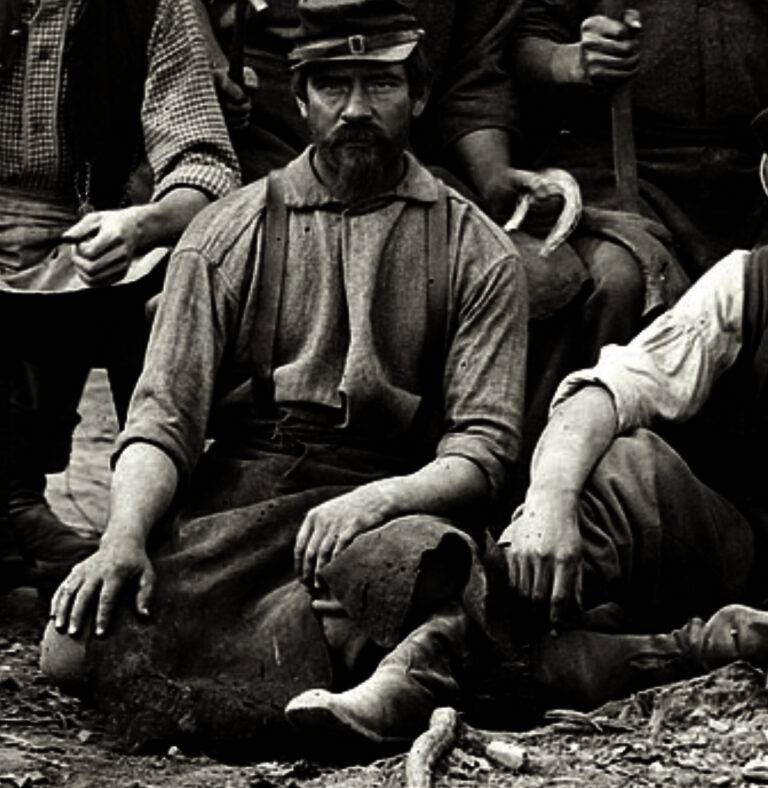

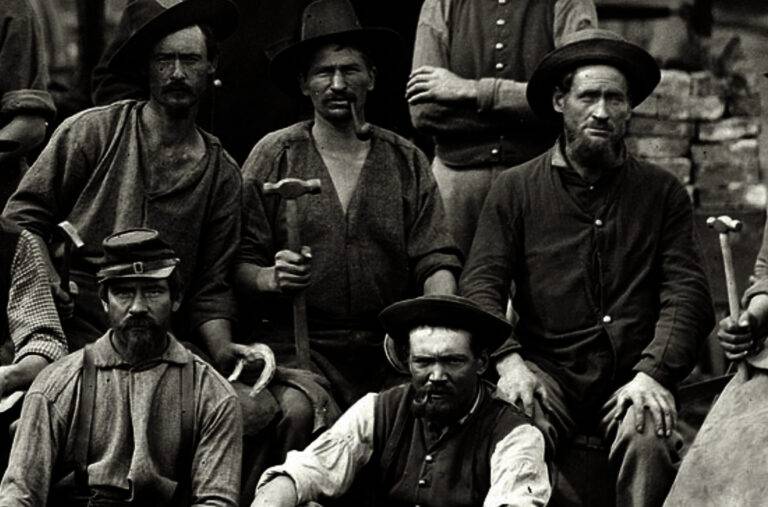

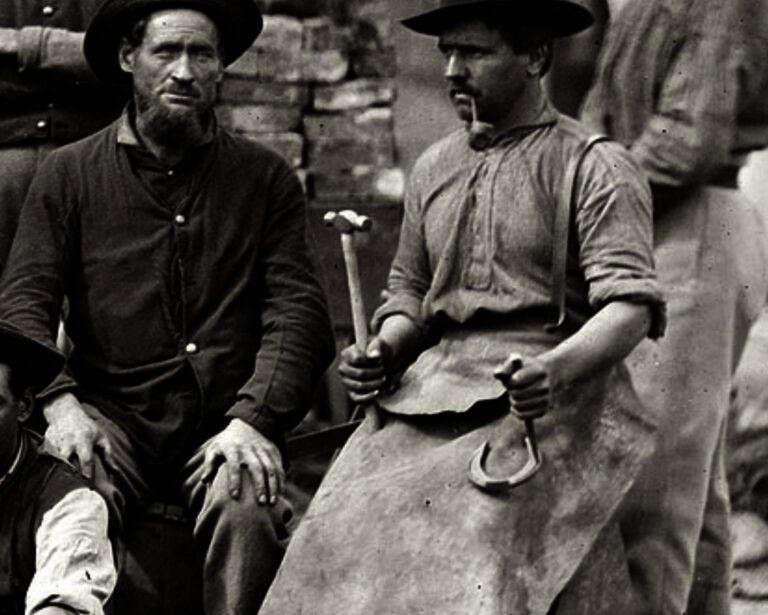

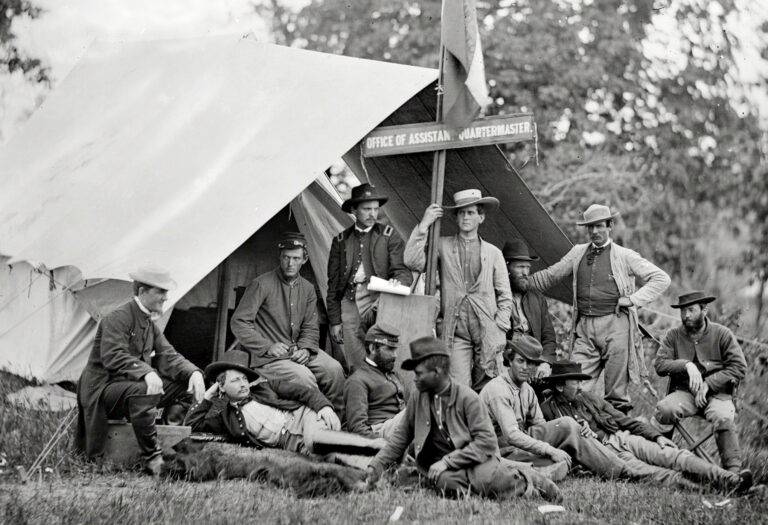

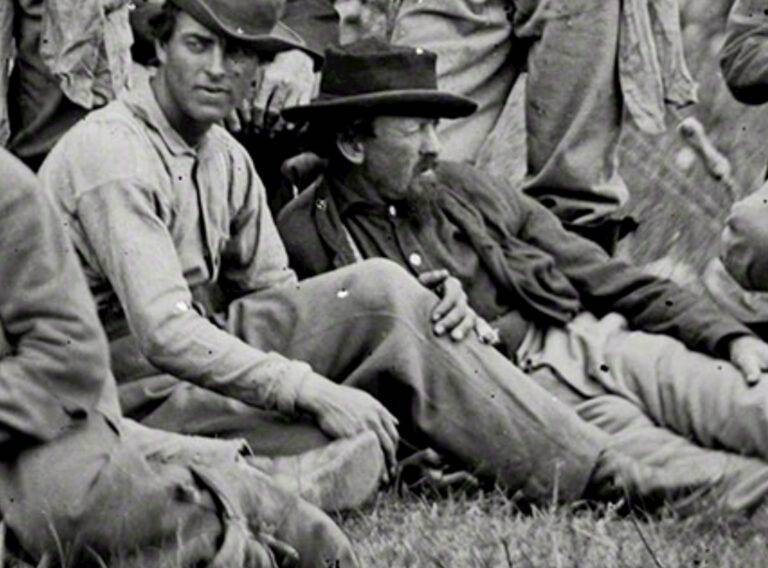

October 1864. Petersburg, Virginia. “Mechanics of 1st Division, 9th Army Corps.” Wet plate glass negative, photographer unknown.

June 1863. “Fairfax Courthouse, Virginia. Capt. J.B. Howard, Office of Assistant Quartermaster, Army of the Potomac.”

Of the shirts that might have been brought home by the veteran for sentimental or practical purposes, many were subsequently used up as work clothes around the farm or shop, eventually making theirway to extinction in the household rag box. By 1875, the stockpile of some 1.7 million shirts in Union clothing depots at the war’s end had been exhausted through issuances to the postwar regular army, state militias and the Freedman’s Bureau and by public auctions of outdated army ~lothing.~It doesnot seem that many shirts, if any, made it into the stocks of military surplus dealers as was the case, quite fortunately, with quantities of Union-issue forage caps, uni- form (dress) hats, overcoats and uniform jackets acquired for commercial resale by the firms of Francis Bannerman, W. Stokes Kirk, White’s and other late nineteenth-century deal- ers in military surplus. These early purveyors of military antiquities passed through their sales roomsmany of the Civil War uniforms, arms, and equipments that form private collec- tions today. As a consequence, the once-common shirt of the Union soldier is, today, astonishingly uncommon; there are very few of them for this future generation to “wonder at.” Even in the absence of a formal survey listing every known example, a casual census suggests there are probably only several dozen surviving shirts with solid provenance of Civil War soldier-use in the hundreds of museums, historical soci- eties and private collections around the country. Among that thin population are Union-issue shirts, state-issue shirts pro- vided in unknown variety and quantity to their respective units, and those purchased by the soldier or gotten from a local aid society or through an entreaty to a loved one at home. The purpose of this article is to provide a broad context for the manufacture and issuance of “the army standard size and make” shirt, and to describe in detail the best surviving example of one. The 1865 Quartermaster’s report stated that more than 11 million shirts had been purchased by Union clothing depots since May 1861.3 These shirts were generally categorized under one oftwo majorfabric types, either”knit,”or”flannel.” Flannel shirts were usually further noted as being either white or gray in color. In four years of war, the principal U. S. clothing depots located in New York, Philadelphia, and Cin- cinnati purchased more than 2.5 million knit shirts from twenty-nine different contractors through at least sixty-five different contracts. The first let for knit shirts were dated in August 1862. Contract language describing these shirts refers to them as “gray knit,” “mixed knit,” “with collars,” or “to be made like sample except that they are to have cuffs instead of elastic wrist bands.” Several knit shirt contracts required a weight of “11 pounds per dozen9’or, similarly, “each to weigh 14 ounce^.”^ Beyond these few meager clues in the contracts, little is known about the Union-issue knit shirt. Of the millions of knit shirts bought by the Quartermaster Department and issued to Union soldiers, not a single shirt of this type is known to survive. The knittingpattern probably resembled that found on machine-knit Civil War officers’ sashes of silk and non- commissioned officers’ sashes of wool. Over the course of the War, the Quartermaster Department awarded knit shirt con- tracts ranging in cost from as little as sixty-nine cents per shirt to as much as $2.34 each. Of the twenty-nine knitting manufactories supplying shirts to the army, most were located in and around Northern industrial centers with established concentrations of capital to underwrite their setup and opera- tion. Fifteen knitting contractors were located in New York City, with another seven in Albany, New York, and environs. Two were located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with one each in Trenton, New Jersey; New Britain, Connecticut; Boston, Massachusetts and Bennington, Verm~nt.~ Knit good contractors producing for the army employed new, expensive, power knittingmachinesdeveloped in the 1850swith capacity for large volume production required to fulfill goveniment shirt contracts.

退役軍人が感傷的なあるいは実用的な目的で家に持ち帰ったシャツのうち、多くはその後、農場や店の周りで作業着として使い古され、最終的には家庭の雑巾箱の中で失われてしまいました。1875年までには、終戦時に北軍の衣料品倉庫に備蓄されていた約170万着のシャツは、戦後の正規軍、州民兵、自由人局への支給や、古くなった軍服の公売によって使い尽くされていました。フランシス・バナーマン、W.ストークス・カーク、ホワイトなどの19世紀末の軍用余剰品の販売業者によって商業的に再販されるために入手された大量の北軍支給のフォーリッジキャップ、ユニフォーム(ドレス)ハット、オーバーコート、ユニフォームジャケットがそうであったように、多くのシャツが軍用余剰品の販売業者の在庫にはなりませんでした。このような初期の軍用骨董品商は、今日個人コレクションを形成している南北戦争の軍服、武器、装備品の多くを、彼らの売り場を通過させました。その結果、かつて一般的だった北軍兵士のシャツは、今日では驚くほど珍しいものとなっています。現存するすべてのシャツをリストアップした正式な調査はありませんが、気軽な国勢調査によれば、南北戦争の兵士が使用した確かな出所のあるシャツは、おそらく全国各地の何百もの博物館、歴史協会、個人コレクションに数十枚しか現存していないと考えられます。そのわずかな数の中には、北軍支給のシャツ、州支給のシャツ、それぞれの部隊に支給された種類も量も不明なもの、兵士が購入したもの、地元の支援団体から入手したもの、故郷の愛する人に懇願して入手したものなどがあります。この記事の目的は、「陸軍標準サイズと製造」のシャツの製造と発行に関する幅広い背景を提供し、現存する最も良い例を詳細に説明することです。1865年のクォーターマスターの報告書によれば、1861年5月以来、北軍の衣料品倉庫で1,100万枚以上のシャツが購入されたという。フランネル・シャツは通常、白かグレーのどちらかでした。戦争中の4年間で、ニューヨーク、フィラデルフィア、シンシナティにあった米国の主要な衣料品倉庫は、少なくとも65の異なる契約を通じて、29の異なる業者から250万枚以上のニットシャツを購入しました。ニットシャツの最初の発注は1862年8月でした。これらのシャツを説明する契約書には、”グレーニット”、”ミックスニット”、”襟付き”、または “手首のゴムバンドの代わりにカフスがある以外は見本と同じように作られる “と記載されていました。いくつかのニットシャツの契約書では、”1ダースあたり11ポンド9オンス”、あるいは同様に “1枚14オンス”という重量が要求されていました。契約書に記載されたこれらのわずかな手がかりを越えて、ユニオン発行のニットシャツについてはほとんど知られていません。クォーターマスター局が購入し、北軍兵士に支給された何百万枚ものニットシャツのうち、このタイプのシャツは一枚も現存していません。編み模様はおそらく、機械編みされた絹の南北戦争将校の帯や、ウールの下士官将校の帯に見られるものに似ていたでしょう。戦争期間中、クォーターマスター省は1着69セントから2.34ドルのニットシャツを発注しました。陸軍にシャツを供給していた29のニット製造所のうち、そのほとんどは北部工業地帯とその周辺にあり、設立と操業のための資本が集中していました。15社のニット業者がニューヨーク市にあり、さらに7社がニューヨーク州オルバニーとその周辺にありました。陸軍向けの優れたニット業者は、1850年代に開発された新型の高価な動力編み機を使用しており、政府とのシャツ契約に必要な大量生産が可能でした。

CANTON FLANNEL

Canton flannel is a medium-weight, plain-woven textile that is prized for its softness, durability, warmth, and versatility. It is typically made from a cotton warp and a wool or cotton weft, and its brushed surface lends it a fuzzy texture and enhanced insulating properties. The term “Canton” refers to the city of Guangzhou in China, where the fabric was first produced and exported to the West during the 18th and 19th centuries. Canton flannel quickly gained popularity in Europe and North America due to its superior quality and performance. Although the fabric is now produced in many countries, the name “Canton flannel” has persisted, and it continues to be associated with this particular type of textile.Canton flannel is used in a wide range of applications, including clothing, bedding, and industrial products. In the apparel sector, it is commonly used for pajamas, robes, blankets, and outerwear. Canton flannel is also a popular choice for children’s sleepwear, as it is soft, warm, and fire-resistant. In industrial settings, Canton flannel is valued for its durability, absorbency, and resistance to abrasion. It is used for a variety of purposes, such as polishing and buffing, machine and equipment cleaning, and industrial wiping and filtering.

Several reputable manufacturers produce Canton flannel, including Burlington Industries, Faribault Woolen Mill Co., and Bemidji Woolen Mills. These companies have a long history of producing high-quality Canton flannel, and they leverage their expertise and experience to create fabrics that meet the specific needs of their customers.

Burlington Industries, for example, is a leading textile company that produces a wide range of fabrics, including Canton flannel. They are committed to innovation, sustainability, and meeting the diverse demands of their customers. Faribault Woolen Mill Co. and Bemidji Woolen Mills, on the other hand, are renowned for their heritage and craftsmanship in producing wool-based textiles, including Canton flannel.

Overall, Canton flannel is a versatile and high-quality textile that is prized for its softness, durability, warmth, and versatility. It is used in a wide range of applications, and it continues to be a popular choice for textile products due to its rich history and continued production by reputable manufacturers.

Canton flannel is used in a wide range of applications, including clothing, bedding, and industrial products. In the apparel sector, it is commonly used for pajamas, robes, blankets, and outerwear. Canton flannel is also a popular choice for children’s sleepwear, as it is soft, warm, and fire-resistant. In industrial settings, Canton flannel is valued for its durability, absorbency, and resistance to abrasion. It is used for a variety of purposes, such as polishing and buffing, machine and equipment cleaning, and industrial wiping and filtering.

カントンフランネルは、綿とウールの混紡で作られた中程度の重さの平織り生地です。柔らかく、暖かく、耐久性に優れていることで知られており、衣類、寝具、工業用途など、さまざまな用途に使用されています。カントンフランネルは、中国の広州市(当時は広東省)にちなんで名付けられました。18世紀と19世紀に最初に生産され、その優れた品質と性能により、西洋で急速に人気を博しました。カントンフランネルは、片面または両面に起毛加工を施して、空気を取り込み、追加の暖かさを提供するふわふわとした起毛を作ります。そのため、冬服、毛布、寝具に最適な素材でした。カントンフランネルは、軽量から重量まで、さまざまな重さで提供される、非常に用途の広い生地でもあります。軽量のカントンフランネルは、シャツ、パジャマ、裏地によく使用され、重量のあるカントンフランネルは、アウターウェア、作業着、工業用途に適しています。耐久性と過酷な条件に耐える能力が評価されています。研磨やバフ研磨などの製造用途、および機械や設備の清掃に一般的に使用されます。個人消費者と企業の両方に人気がありました。消費者は、その柔らかさ、暖かさ、耐久性を高く評価しており、企業は、工業用途でのその汎用性と性能を高く評価しています。いくつかの信頼できるメーカーがカントンフランネルの製造を専門としています。これらの会社は、顧客の特定のニーズを満たす高品質の生地を製造する長い歴史を持っています。総合的に、カントンフランネルは、幅広い用途に使用できる、用途の広く耐久性のある生地です。柔らかく、暖かく、耐久性があり、吸収性があり、耐火性があります。そのため、衣類、寝具、工業用途に人気がありました。

工業用途では、研磨やバフがけ、機械や装置のクリーニング、工業用ワイピングやフィルターなど、さまざまな用途に使用されてきました。カントンフランネルは、バーリントン・インダストリーズ社、ファリボルト・ウーレン・ミル社、ベミジ・ウーレン・ミルズ社など、評判の高いいくつかのメーカーが製造していました。これらの企業は、高品質のカントンフランネルを生産してきた長い歴史があり、その専門知識と経験を活かして、顧客の特定のニーズを満たす生地を生産していました。例えば、バーリントン・インダストリーズは、カントンフランネルを含む様々な生地を生産する大手繊維企業でした。同社は技術革新、持続可能性、そして顧客の多様な要求に応えることに尽力していました。一方、ファリボルト・ウーレン・ミルズ社とベミジ・ウーレン・ミルズ社は、カントンフランネルを含むウールベースのテキスタイルを生産する伝統と職人技で有名でした。このように、カントンフランネルは、その柔らかさ、耐久性、保温性、多用途性で、高く評価されてきました。また、その豊かな歴史と信頼できる製造業者による継続的な生産により、繊維製品として人気の高い選択肢であり続けています。

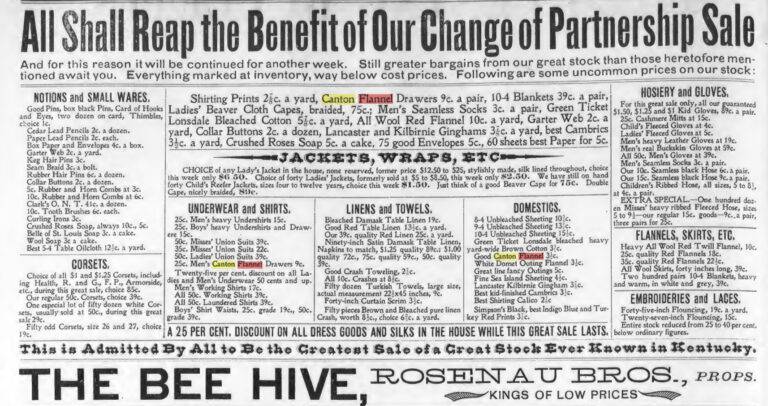

Maysville KY Evening Bulletin 1898

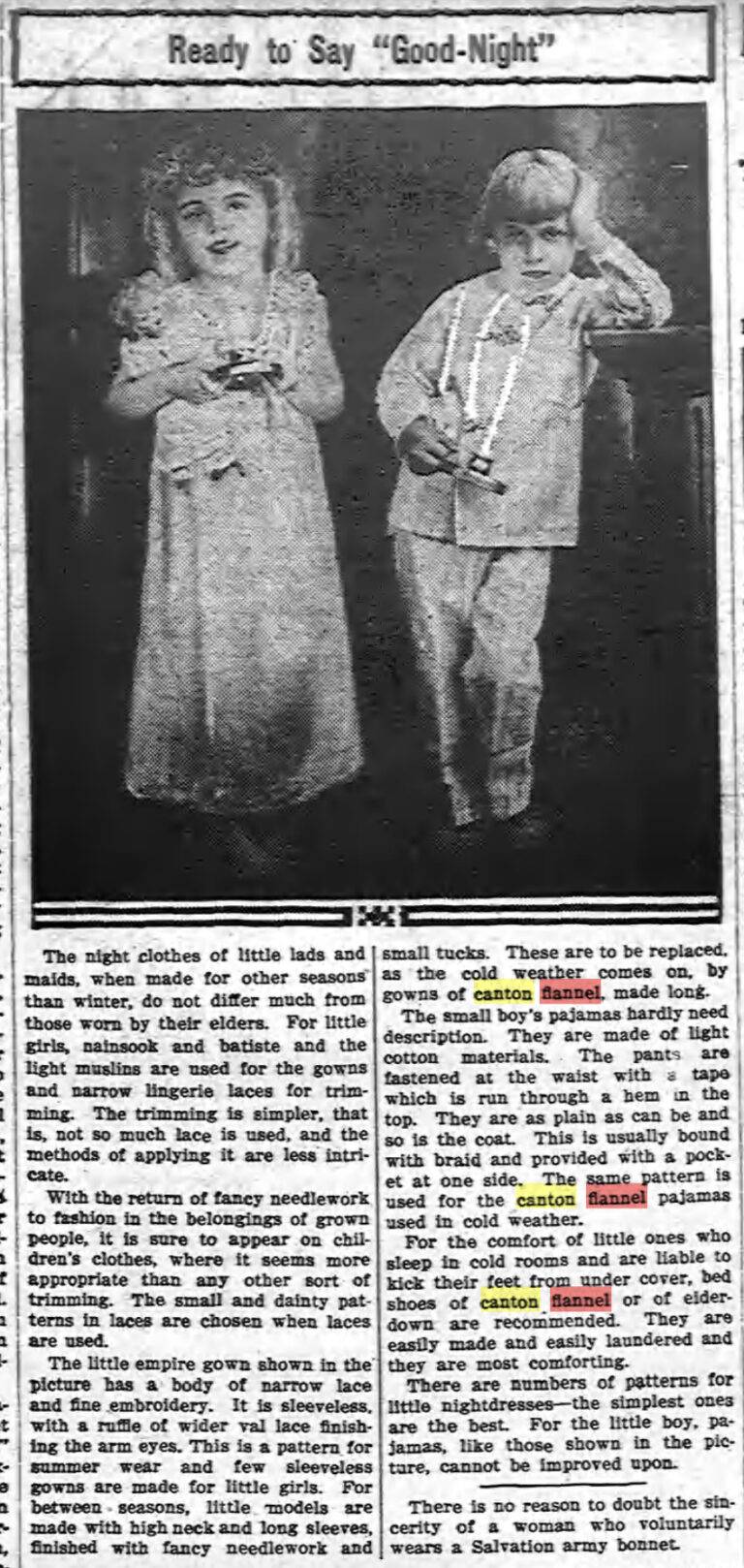

Paterson NJ Morning Call 1900

Virden IL Reporter 1914 Oct-Dec 1916

Faribault Woolen Mill

Founded in 1865, Faribault Woolen Mill Co. produces timeless, handcrafted blankets, decorative throws, apparel and accessories, most of which are made in one of the oldest existing woolen mills in America. From providing woolen blankets for pioneers heading west and comforting our troops through two world wars, to today’s products that are built to last, the brand is woven into American history and is a living testament to American entrepreneurship. Faribault Woolen Mill Co. is proud to offer products Made in the USA.

廣東フランネル

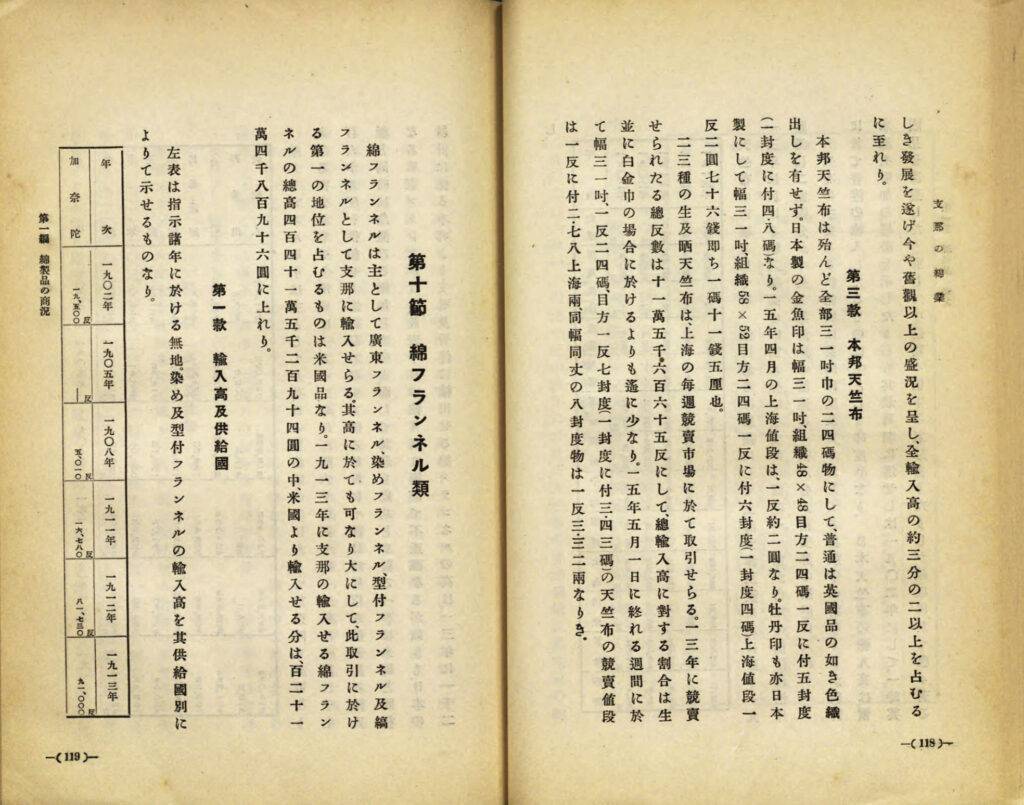

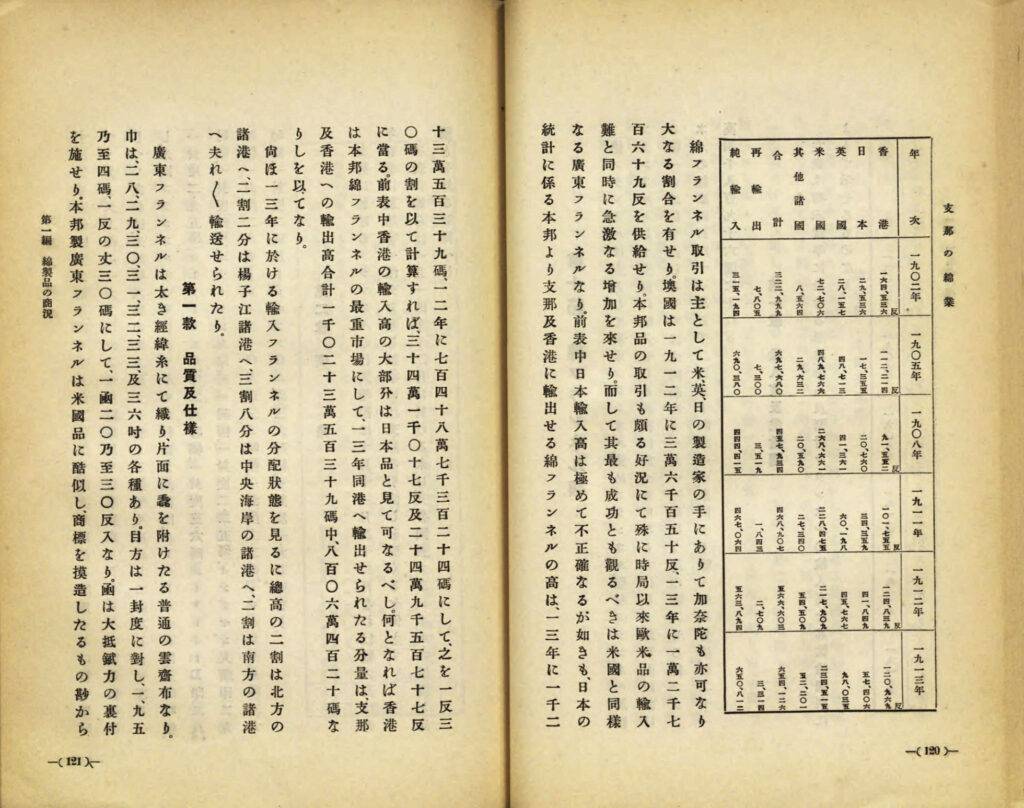

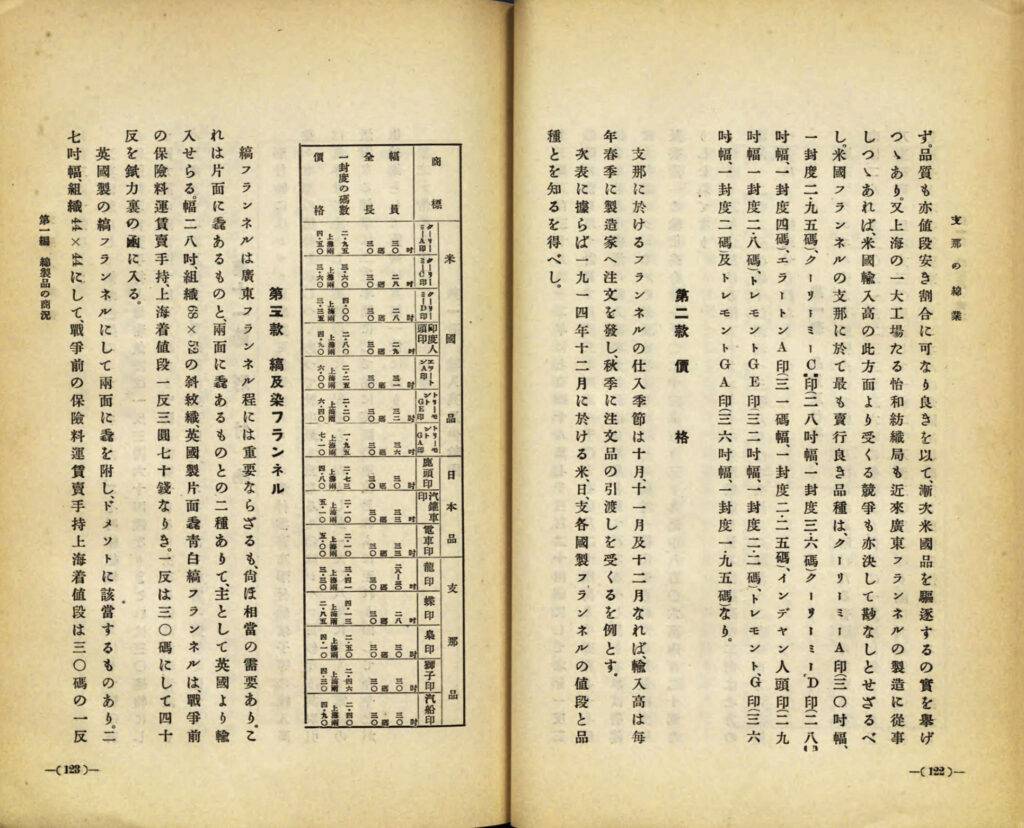

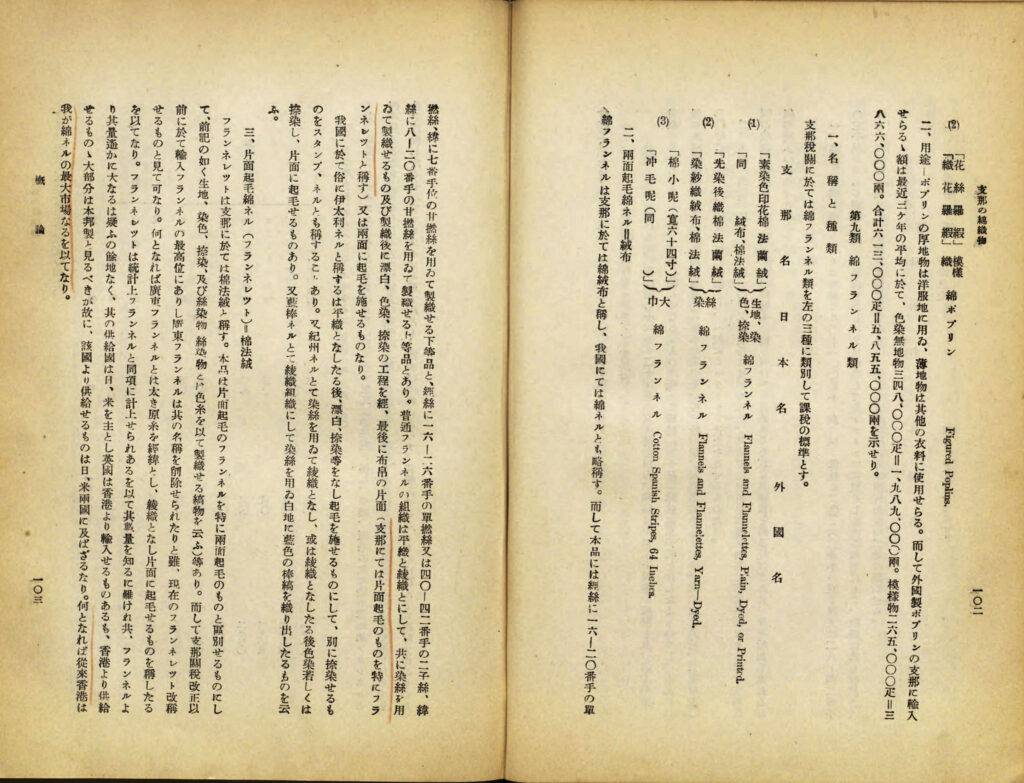

廣東フランネルは太さ經緯糸にて織り片面に毳(けば=柔らかい毛織物)を附けたる普通の雲斎布なり。(中略) 本邦製廣東フランネルは米國品に酷似し商標を模造したるもの尠(すくな)からず、品質も亦値段の安さ割合に可なり良きを似て、漸(ようや)く米國品を駆逐するの實を擧げつつあり又上海の一大工場たる怡和紡織局も近來廣東フランネルの製造に従事しつつあれば米國輸入高の此方面より受くる競争も亦決して尠なしとざるべし。

Canton flannel is a common flannel cloth that is woven with coarse warp and weft threads and has a nap on one side. (Omitted) Japanese-made Canton flannel is often similar to American products, and there are many products that imitate American trademarks. The quality is also relatively good in proportion to the low price, and it is gradually driving out American products. In addition, the Yihe Textile Bureau, a major factory in Shanghai, has recently been engaged in the production of Canton flannel. Therefore, it is certain that the competition from the United States in this area will not be small.

Overall, Canton flannel is a versatile and high-quality textile that is prized for its softness, durability, warmth, and versatility. It is used in a wide range of applications, and it continues to be a popular choice for textile products due to its rich history and continued production by reputable manufacturers.

Canton flannel is used in a wide range of applications, including clothing, bedding, and industrial products. In the apparel sector, it is commonly used for pajamas, robes, blankets, and outerwear. Canton flannel is also a popular choice for children’s sleepwear, as it is soft, warm, and fire-resistant. In industrial settings, Canton flannel is valued for its durability, absorbency, and resistance to abrasion. It is used for a variety of purposes, such as polishing and buffing, machine and equipment cleaning, and industrial wiping and filtering.

支那の綿業 1917

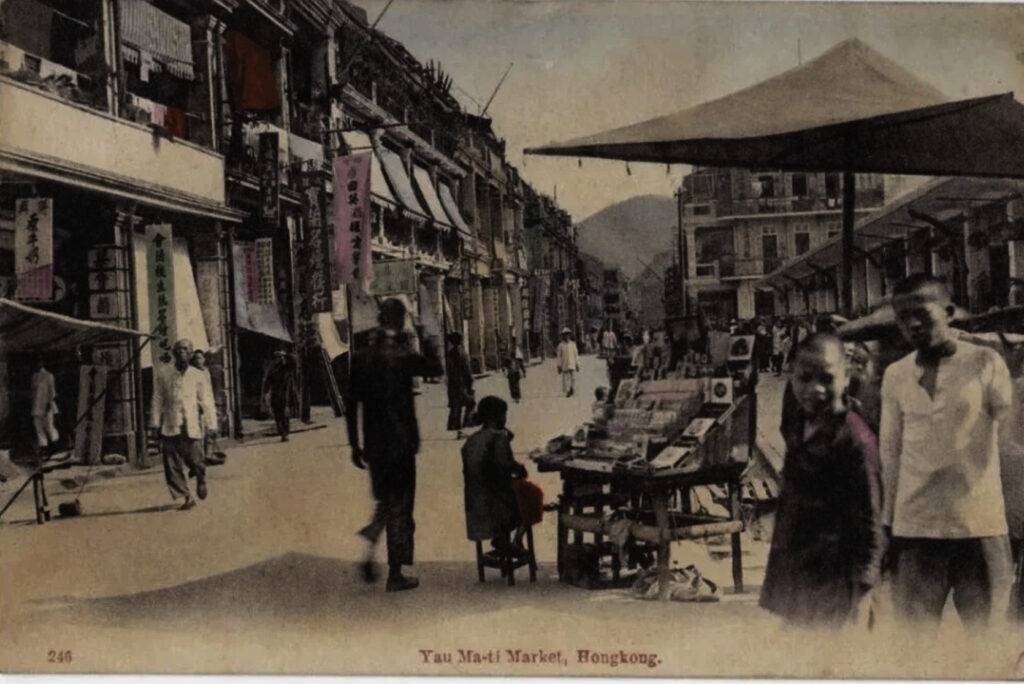

1912年頃 油麻地市場

– recommendation –

What is the flannel ? VOl.1

Flannel fabric is a warm and comfortable material that is perfect for chilly seasons. It has a unique texture that feels soft and inviting against the skin. Flannel fabric also offers exceptional insulation, making it a great choice for keeping warm in cold weather. Whether you are looking for a cozy shirt to wear on a cold day or a stylish to wear out on the town, flannel fabric is a great option.In this issue, we take a look at the history of flannel and its secrets.

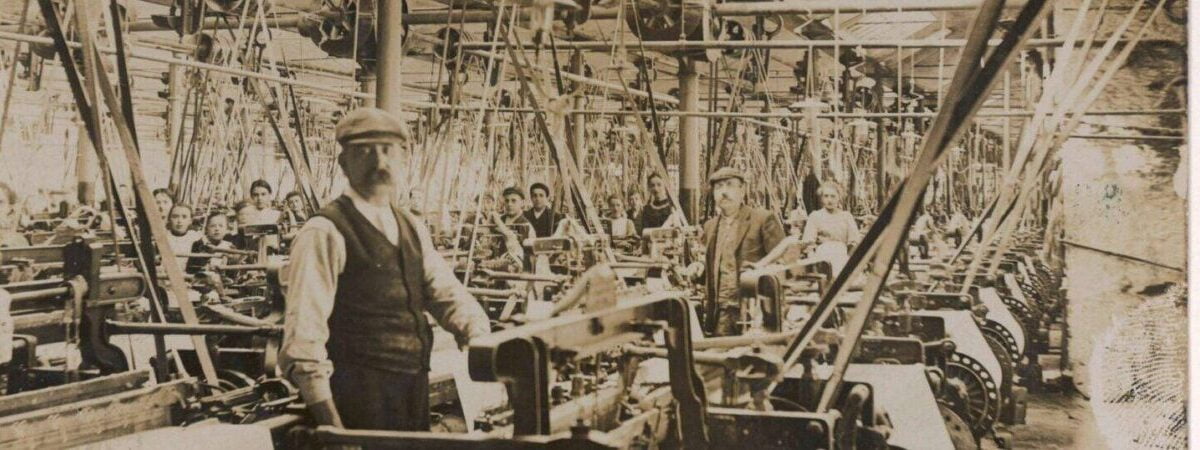

"FUSTIAN" THE STARTING THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Do you know the name of the fabric “fustian”? It is not a well-known name today, but it is actually a very important material for the Industrial Revolution, as well as for its long history. The term “fustian” varies from period to period, as there are several combinations of materials used in different periods. In this issue, we will study the relationship between “fustian” and the Industrial Revolution.