THE FIBER

You can search about the Fiber knowledge.

Text By KATS TANAKA

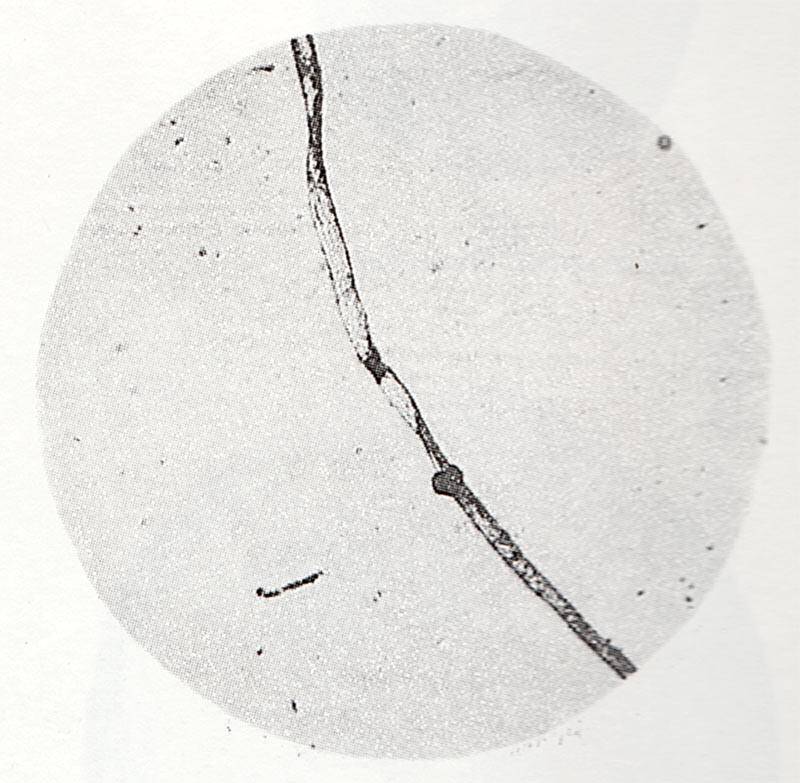

Cotton is a soft, fluffy short staple fibre that grows in a ball around the cotton seed of the genus Gossypium of the mallow family.The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor percentages of waxes, fats, pectins, and water. Under natural conditions, the cotton bolls will increase the dispersal of the seeds.

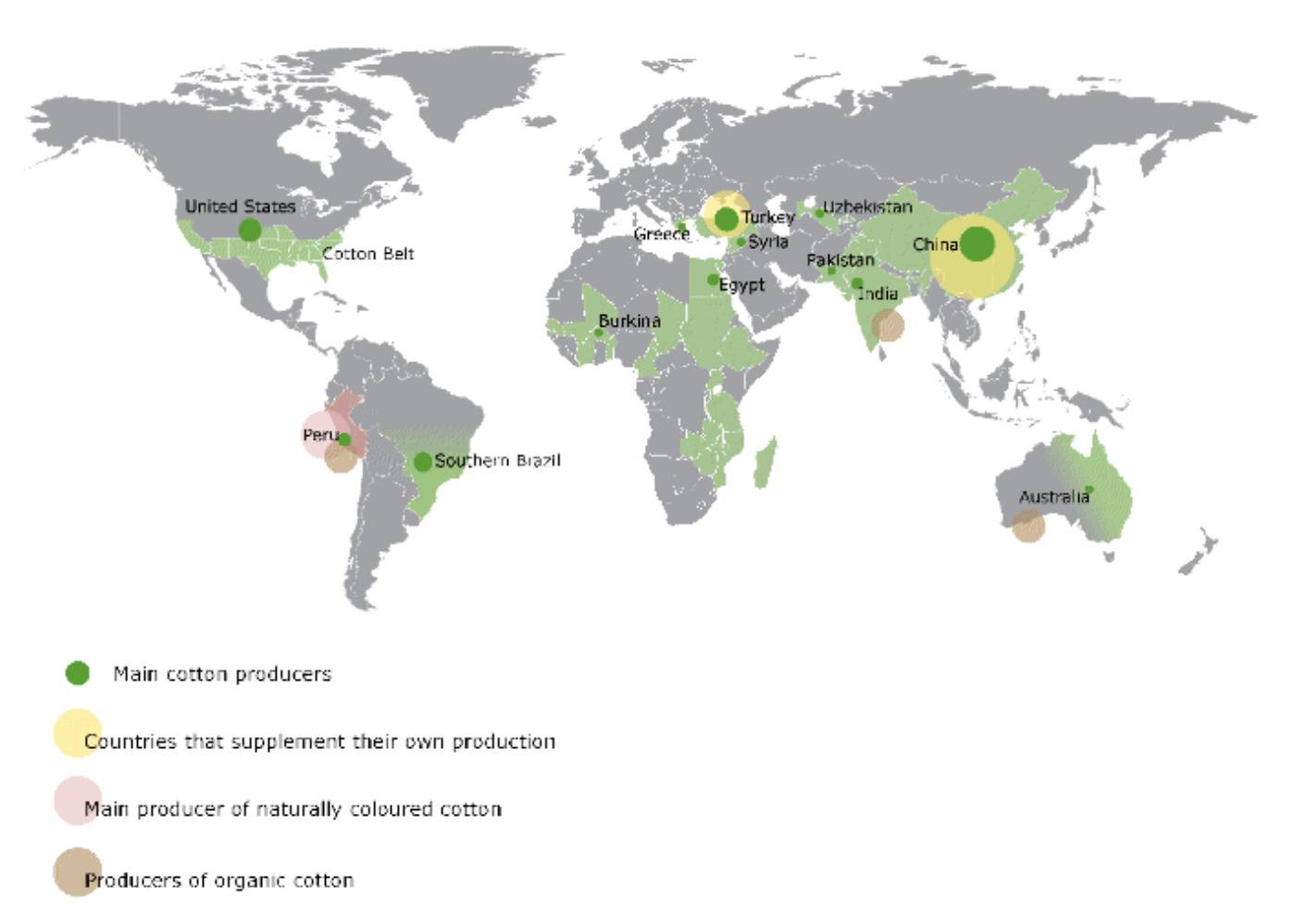

The plant is a shrub native to tropical and subtropical regions around the world, including the Americas, Africa, Egypt and India. The greatest diversity of wild cotton species is found in Mexico, followed by Australia and Africa. Cotton was independently domesticated in the Old and New Worlds.

The fiber is most often spun into yarn or thread and used to make a soft, breathable, and durable textile. The use of cotton for fabric is known to date to prehistoric times; fragments of cotton fabric dated to the fifth millennium BC have been found in the Indus Valley civilization, as well as fabric remnants dated back to 4200 BC in Peru. Although cultivated since antiquity, it was the invention of the cotton gin that lowered the cost of production that led to its widespread use, and it is the most widely used natural fiber cloth in clothing today.

Current estimates for world production are about 25 million tonnes or 110 million bales annually, accounting for 2.5% of the world’s arable land. India is the world’s largest producer of cotton. The United States has been the largest exporter for many years.Today, cotton is grown in many countries around the world, including the United States, India, China, and Uzbekistan, and is used in a wide range of products, from clothing and bedding to industrial goods.

However, there are pros and cons of cotton production despite its widespread use due to concerns about the environmental impact of cotton cultivation and the labour practices, child labour and human rights issues in cotton-producing countries that have been pointed out for some time.

コットンはアオイ科ゴシピウム属の綿花の種子の周りにある毬(まり・けまり)の中で育つ柔らかくてふわふわした短繊維です。繊維はほぼ純粋なセルロースでわずかにワックス、脂肪、ペクチン、水分が含まれています。自然条件下では綿の胆嚢が種子の飛散、増加させます。アメリカ大陸、アフリカ、エジプト、インドなど、世界中の熱帯・亜熱帯地域に自生する低木植物です。綿花の野生種が最も多様なのはメキシコで、次いでオーストラリア、アフリカです。綿花は長い時間をかけて独自に栽培化されました。

繊維は糸に紡がれ、柔らかく、通気性と耐久性に優れた織物に使用されることが最も多いです。インダス川流域の文明では紀元前5千年頃の綿織物が発見されておりペルーでは紀元前4200年頃の綿織物が発見されています。古代より栽培されていましたが英国の産業革命を機に綿繰機の発明により生産コストが下がったことが普及のきっかけとなり現在では天然繊維の布として最も多く衣料に使用されています。現在の推定では世界の生産量は年間約2500万トン、1億1000万俵で、世界の耕地面積の2.5%を占めています。世界最大の綿花生産国はインドです。米国は長年にわたり最大の輸出国となっていました。綿花は米国、インド、中国、ウズベキスタンなど世界各国で栽培され衣類や寝具から工業製品まで幅広く使用されています。しかし、綿花栽培が環境に与える影響や、以前から指摘されている綿花生産国の労働慣行・児童労働・人権問題への懸念から広く使用されているにもかかわらず綿花生産には賛否両論存在しています。

There are four main types of cotton, all of which have been cultivated by humans over a long period of time since ancient times:

・Gossypium hirsutum – upland cotton, native to Central America, Mexico, the Caribbean and southern Florida (90% of world production)

・Gossypium barbadense – known as extra-long staple cotton, native to tropical South America (8% of world production)

・Gossypium arboreum – tree cotton, native to India and Pakistan (less than 2%)

・Gossypium herbaceum – Levant cotton, native to southern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula (less than 2%)

Hybrid varieties are also cultivated. The two New World cotton species account for the vast majority of modern cotton production, but the two Old World species were widely used before the 1900s. While cotton fibers occur naturally in colors of white, brown, pink and green, fears of contaminating the genetics of white cotton have led many cotton-growing locations to ban the growing of colored cotton varieties.

G. barbadense originated in southwest Ecuador and northwest Peru. It is now cultivated around the world, including China, Egypt, Sudan, India, Australia, Peru, Israel, the southwestern United States, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. It accounts for about 5% of the world’s cotton production.

綿花には大きく4つの種類がありいずれも古代より長い時間をかけて人間によって栽培化された品種です。

・Gossypium hirsutum – 中米、メキシコ、カリブ海、フロリダ南部原産の陸上綿花(世界の生産量の90%)

・Gossypium barbadense – 超長綿として知られ、南米熱帯地方が原産(世界の生産量の8%)

・Gossypium arboreum – インド、パキスタン原産の木綿(2%未満)。

・Gossypium herbaceum – レバント綿、アフリカ南部とアラビア半島原産(2%未満)。

現在ではそのハイブリッド品種も栽培されています。現代の綿花生産の大部分は新世代の2種が占めているが1900年代以前は旧世代の2種も広く利用されていました。綿花の繊維には、白、茶、ピンク、緑などの色が自然界に存在しますが、白綿の遺伝子汚染を防ぐ目的で、多くの綿花栽培地での有色品種栽培は禁止されています。

コットンの語源はアラビア語で、قطن(qutnまたはqutun)が語源です。中世のアラビア語ではこれが通常の綿の意味でした。マルコ・ポーロは著書「東方見聞録(伊:Il Milione)」の第2章で、トルキスタン、現在の新疆ウイグル自治区のホータンと呼ぶ地方で綿花が豊富に栽培されていたと記述しています。この言葉は12世紀半ばにロマンス語にその1世紀後にはフランスを経由して英語にも変化していくことになります。綿織物は古代ローマ人にも輸入品として知られていましたが、中世後期にアラビア語圏から低価格のものが輸入されるまで、ロマンス語(主にラテン語)圏では綿花は珍重されていました。

13世紀後半、「綿花の種子を含む白い繊維状の物質」古フランス語のコトン(12世紀)から最終的には(プロヴァンス語、イタリア語、古スペイン語経由で)アラビア語のqutn、おそらくエジプト起源の言葉から派生しました。またオランダ語 katoen、ドイツ語 Kattun、プロヴァンス語 coton、イタリア語 cotone、スペイン語 algodon、ポルトガル語 algodo も最終的にはアラビア語から派生した言葉です。15世紀初頭から「綿でできた布」として。綿の植物」という意味は1400年頃からのもの。形容詞としての「綿で作られた」と表記され出したのは1550年代から。綿繰り機は1794年から記録されています。チェルシー・フィジック・ガーデンのフィリップ・ミラーが1732年にアメリカの植民地ジョージアに最初の綿花の種を送ったと記載されています。

5000 BCE: Cotton is cultivated and spun into cloth in the Indus Valley civilization in ancient India.

1000 BCE: Cotton is grown and used for clothing in ancient Egypt.

800 BCE: Cotton is grown and used in ancient Greece.

100 CE: The use of cotton spreads to the Roman Empire.

7th century: Arab traders introduce cotton to the Islamic world.

14th century: Cotton becomes an important export for the Muslim world, with cotton textiles being traded along the silk road and throughout the Mediterranean.

16th century: Spanish and Portuguese traders introduce cotton to the Americas.

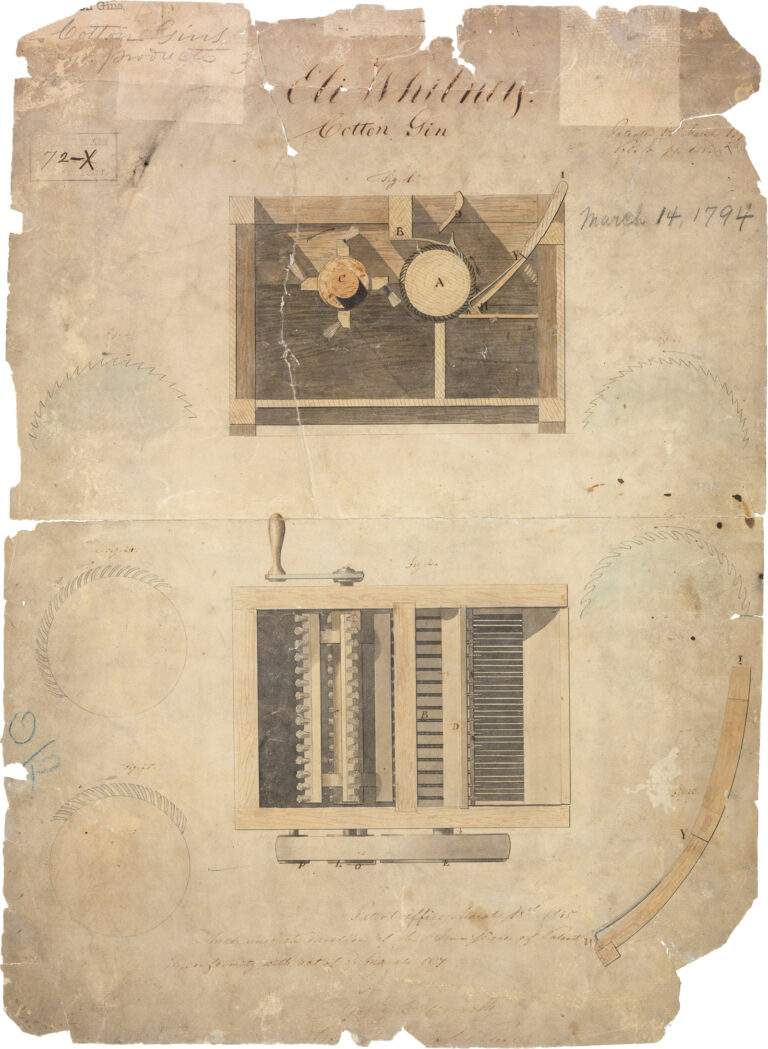

1793: American inventor Eli Whitney invents the cotton gin, greatly increasing the efficiency of cotton production.

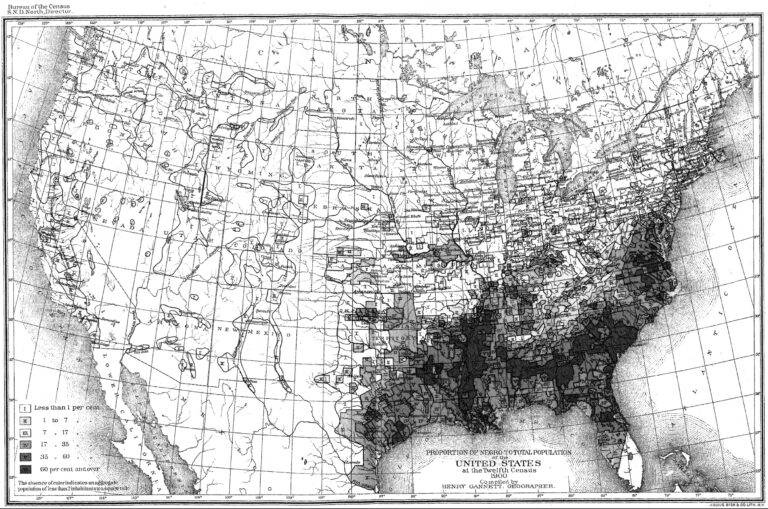

19th century: Cotton becomes a major cash crop in the United States, with the growth of large-scale cotton plantations in the American South.

20th century: Cotton production spreads to other parts of the world, including India, China, and Uzbekistan.

Today: Cotton is one of the most widely used fibers in the world and is a major agricultural product in many countries. However, the environmental impact of cotton farming and concerns about labor practices remain controversial issues.

紀元前5000年。古代インドのインダスバレー文明で綿花が栽培され、布に紡がれる。

紀元前1000年 古代エジプトで綿花が栽培され、衣服として使用される。

紀元前800年 古代ギリシャで綿花が栽培され、使用される。

紀元前100年 ローマ帝国で綿花の使用が広まる。

7世紀 アラブの商人により、イスラム世界に綿花が伝えられる。

14世紀 綿花はイスラム世界の重要な輸出品となり、綿織物はシルクロードや地中海沿岸で取引されるようになる。

16世紀 スペインとポルトガルの商人により、アメリカ大陸に綿花がもたらされる。

1793: アメリカの発明家イーライ・ホイットニーが綿繰り機を発明し、綿花の生産効率を大幅に向上させる。

19世紀 アメリカ南部で大規模な綿花プランテーションが展開され、綿花が主要な換金作物となる。

20世紀 インド、中国、ウズベキスタンなど、世界各地に綿花生産が広がる。

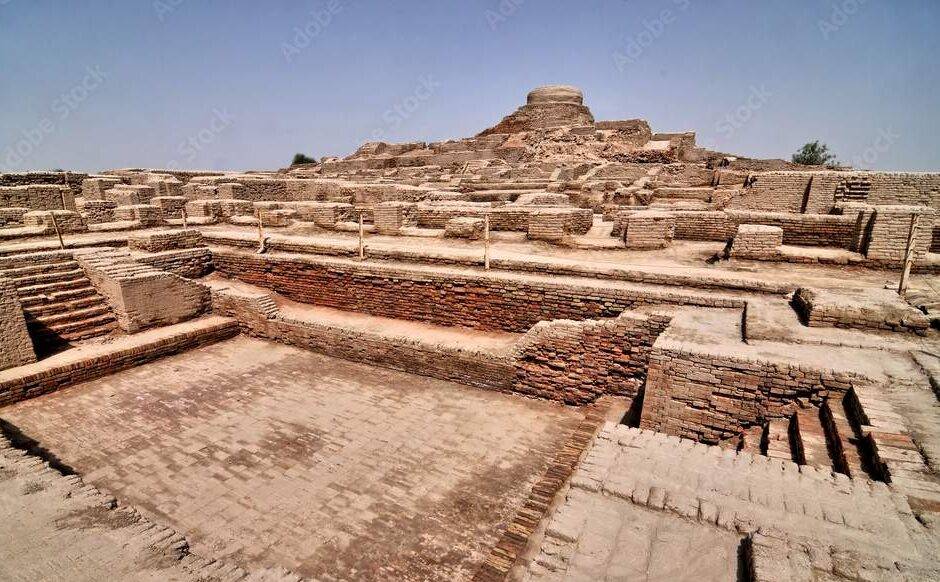

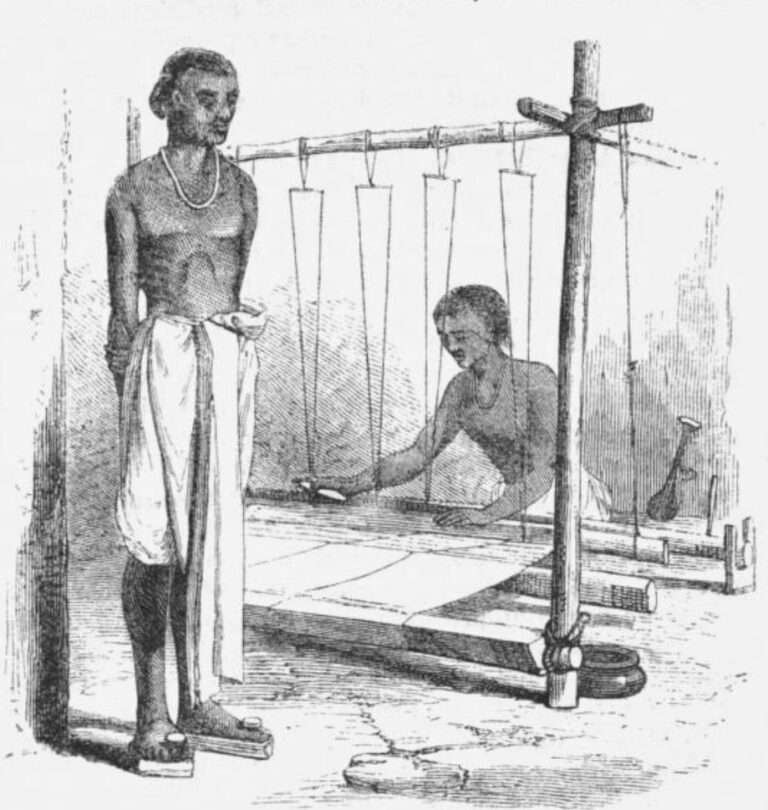

“Farmers in the Indus valley were the first to spin and weave cotton. In 1929 archaeologists recovered fragments of cotton textiles at Mohenjo-Daro, in what is now Pakistan, dating to between 3250 and 2750 BCE. Cottonseeds founds at nearby Mehrgarh have been dated to 5000 BCE. Literary references further point to the ancient nature of the subcontinent’s cotton industry. The Vedic scriptures, composed between 1500 and 1200 BCE allude to cotton spinning and weaving”

紀元前5500年頃、銅製のビーズに保存されていた最古の綿花使用例は、古代インドのボラン峠の麓、現在のパキスタン・バローチスターンにある新石器時代の遺跡メアガルで発見されています。青銅器時代のインダスバレー文明の遺跡であるモヘンジョダロなどからは綿織物の断片も見つかっており当時から綿は重要な輸出品であった可能性があります。

現時点ではインダス川流域の農民が初めて綿花を紡ぎ織った とされています。1929年考古学者は現在のパキスタンにあるモヘンジョダロにて紀元前3250年から2750年にかけての綿織物の断片を発見。また近くのメアガルで発見された綿の種は紀元前5000年前後のものと推定されています。それとは別に綿花産業が古くから行われていたことは文献からもうかがうことができます。紀元前1500年から1200年にかけて書かれたヴェーダ聖典には綿花の紡績や織物について書き記されています。

In Peru, cultivation of the indigenous cotton species Gossypium barbadense has been dated, from a find in Ancon, to c. 4200 BC,and was the backbone of the development of coastal cultures such as the Norte Chico, Moche, and Nazca. Cotton was grown upriver, made into nets, and traded with fishing villages along the coast for large supplies of fish. The Spanish who came to Mexico and Peru in the early 16th century found the people growing cotton and wearing clothing made of it.

メキシコのテワカン近郊の洞窟で発見された綿花は紀元前5500年とされていますがこの年代測定には異論もあります。この時代にはサンチャゴ川とバルサ川の間の人々は綿花を栽培、紡ぎ、織り、染め、縫製していた可能性が高い。自分たちで使わない分はアステカの支配者に貢物として送りその規模は年間1億1600万ポンドにも及んだとされます。

ペルーでは、在来種綿花”Gossypium barbadense”の栽培はアンコン遺跡での発見から紀元前4200年頃とされ、ノルテ・チコ、モチェ、ナスカなどの沿岸文化の発展するきっかけとなったと言われている。綿花は川上で栽培され後に網に加工、海岸沿いの漁村と取引され、それの見返りとして食料として魚が供給されるという循環であったと推測されている。16世紀初頭にメキシコやペルーにやってきたスペイン人は人々が綿花を栽培しその綿花で作られた衣服を着ていたと記録している。

ギリシャ人やアラブ人はマケドニアのアレクサンダー大王の東方遠征まで綿花になじみがありませんでした。同時代のメガステネスはセレウコス1世ニカトルに対し『インディカ』で「毛が生える木がある」と語っています。これはインド亜大陸原産の木綿”Gossypium arboreum”のことを指しているとされています。

綿花は有史以前から紡ぎ織られ染色され古代インドの人々の衣服となっていました。当時はすでに古代インド、エジプト、中国の人々の衣服として使われていました。キリスト教時代より何百年も前にインドでは綿織物が卓越した技術で織られておりその用途は地中海沿岸の国々にも広がりました。

アレキサンダー大王がインダス川を下り、ペルシャの海岸からティギース川まで航海するために雇った提督ネアカスの記述(紀元前327年)、航海士アリアンの『アレクサンドロス史』にも以下のように掲載されている。「インド人は麻の衣を着ていたが、その中身は木に生えていたものである。

ペルシャ(現イラン)では、綿花の歴史はアケメネス朝時代(紀元前5世紀)にさかのぼります。しかしながらイスラム教以前のイランでの綿花栽培に関する資料は現在のところほとんど出土されていません。綿花栽培は、メルヴ、レイ、パースで一般的に行われていたとされています。ペルシャの詩、特にフェルドウシ(Ferdowsi)の叙事詩には綿花(ペルシャ語「パンベ」)に関する記述があります。またマルコ・ポーロ(13世紀)はペルシャの主要産物の中に綿花を含まれることを記載しています。17世紀にサファヴィー朝ペルシャを訪れたフランスの旅行家ジョン・シャルダンがペルシャには広大な綿花農場を讃えている一文があります。

Cotton (Gossypium herbaceum Linnaeus) may have been domesticated 5000 BC in eastern Sudan near the Middle Nile Basin region, where cotton cloth was being produced. Around the 4th century BC, the cultivation of cotton and the knowledge of its spinning and weaving in Meroë reached a high level. The export of textiles was one of the sources of wealth for Meroë. Ancient Nubia had a “culture of cotton” of sorts, evidenced by physical evidence of cotton processing tools and the presence of cattle in certain areas. Some researchers propose that cotton was important to the Nubian economy for its use in contact with the neighboring Egyptians. Aksumite King Ezana boasted in his inscription that he destroyed large cotton plantations in Meroë during his conquest of the region.

In the Meroitic Period (beginning 3rd century BCE), many cotton textiles have been recovered, preserved due to favorable arid conditions. Most of these fabric fragments come from Lower Nubia, and the cotton textiles account for 85% of the archaeological textiles from Classic/Late Meroitic sites. Due to these arid conditions, cotton, a plant that usually thrives moderate rainfall and richer soils, requires extra irrigation and labor in Sudanese climate conditions. Therefore, a great deal of resources would have been required, likely restricting its cultivation to the elite. In the first to third centuries CE, recovered cotton fragments all began to mirror the same style and production method, as seen from the direction of spun cotton and technique of weaving. Cotton textiles also appear in places of high regard, such as on funerary stelae and statues.

In the Meroitic Period (beginning 3rd century BCE), many cotton textiles have been recovered, preserved due to favorable arid conditions. Most of these fabric fragments come from Lower Nubia, and the cotton textiles account for 85% of the archaeological textiles from Classic/Late Meroitic sites. Due to these arid conditions, cotton, a plant that usually thrives moderate rainfall and richer soils, requires extra irrigation and labor in Sudanese climate conditions. Therefore, a great deal of resources would have been required, likely restricting its cultivation to the elite. In the first to third centuries CE, recovered cotton fragments all began to mirror the same style and production method, as seen from the direction of spun cotton and technique of weaving. Cotton textiles also appear in places of high regard, such as on funerary stelae and statues.

南エジプトからスーダンのナイル川近辺で栄えたクシュ王国。綿花 “Gossypium herbaceum Linnaeus”は紀元前5000年頃にスーダン東部のナイル川中流域付近で栽培化され綿布が生産されていたと考えられています。 前4世紀頃遷都したメロエ時代に綿花栽培とその紡織の知識が高い水準に達したとされています。織物の輸出はメロエの富の源泉の1つでした。古代ヌビアには一種の「綿花文化」があり綿花加工用具の物的証拠や特定の地域に牛が生息していたことなどがその証拠に当たるとされている。アクスム人のエザナ王は征服時にメロエの大規模な綿花農園を破壊したことを碑文で自慢しています。

遷都後のメロア期(前3世紀初頭)には乾燥した好条件により保存された綿織物が多数出土しています。これらの織物片の多くは下ヌビアから出土し古典期・後期メロア(メロエ)期の遺跡から出土する考古学的織物の85%を綿織物が占めます。この乾燥した条件は通常は適度な降雨と豊かな土壌で育つ植物である綿なのでスーダンの気候条件では特別な灌漑と労働を必要とすることになります。紀元1世紀から3世紀にかけて出土した綿花片は紡績綿の方向や織りの技法から見て同じスタイルと生産方法を反映しています。 綿織物は葬祭用の墓碑や像などの高い地位に値する物にも採用されていました。

Egyptians grew and spun cotton in the first seven centuries of the Christian era.

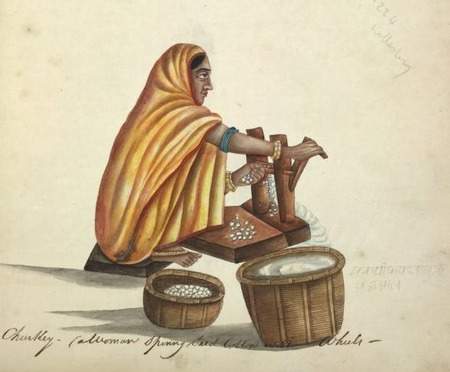

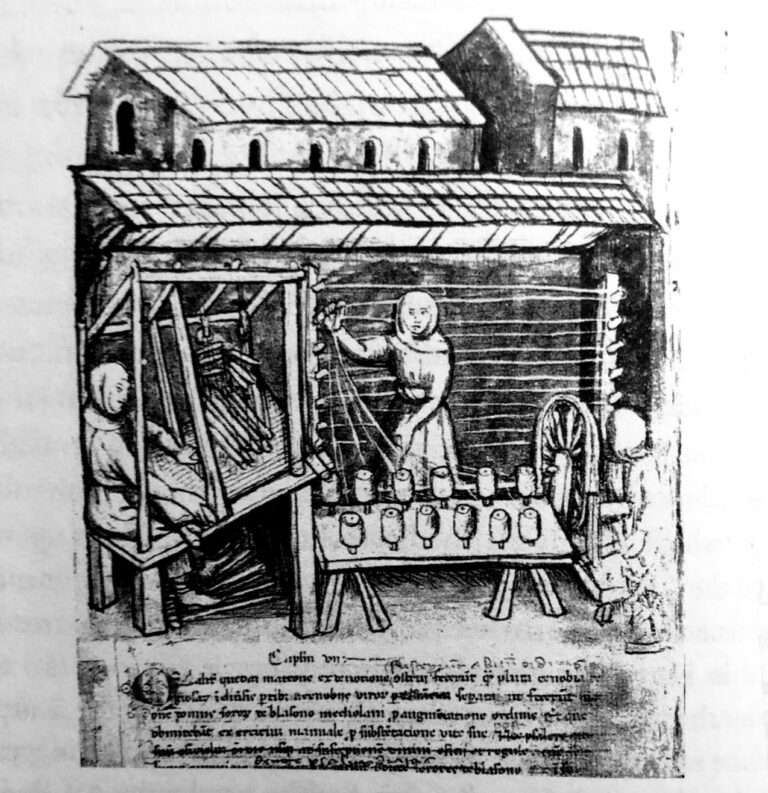

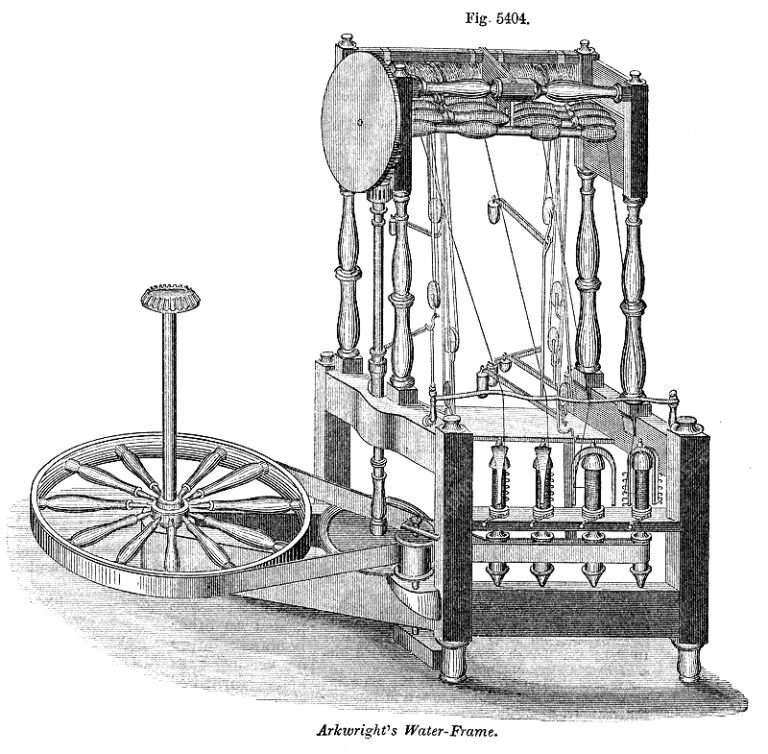

Handheld roller cotton gins had been used in India since the 6th century, and was then introduced to other countries from there. Between the 12th and 14th centuries, dual-roller gins appeared in India and China. The Indian version of the dual-roller gin was prevalent throughout the Mediterranean cotton trade by the 16th century. This mechanical device was, in some areas, driven by water power. The earliest clear illustrations of the spinning wheel come from the Islamic world in the eleventh century. The earliest unambiguous reference to a spinning wheel in India is dated to 1350, suggesting that the spinning wheel was likely introduced from Iran to India during the Delhi Sultanate.

Thomas Browne’s Pseudodoxia Epidemica named it as the Boramez.

In Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopædia, Agnus scythicus was described as a kind of zoophyte, said to grow in Tartary, resembling the figure and structure of a lamb. It was also called Agnus Vegetabilis, Agnus Tartaricus and bore the reported endonyms of Borometz, Borametz and Boranetz.

In his book, The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary (1887), Henry Lee describes the legendary lamb as believed to be both a true animal and a living plant. However, he states that some writers believed the lamb to be the fruit of a plant, sprouting forward from melon-like seeds. Others, however, believed the lamb to be a living member of the plant that, once separated from it, would perish. The vegetable lamb was believed to have blood, bones, and flesh like that of a normal lamb. It was connected to the earth by a stem, similar to an umbilical cord, that propped the lamb up above ground. The cord could flex downward, allowing the lamb to feed on the grass and plants surrounding it. Once the plants within reach were eaten, the lamb died. It could be eaten, once dead, and its blood supposedly tasted sweet like honey. Its wool was said to be used by the native people of its homeland to make head coverings and other articles of clothing. The only carnivorous animals attracted to the lamb-plant (other than humans) were wolves.

1819年フランス人のルイ・アレクシス・ジュメルは、エジプトの統治者モハメド・アリ・パシャに、フランス市場向けにエジプトで超長綿のマホ”Gossypium barbadense”を栽培すれば大きな収入が得られると提案しました。モハメド・アリ・パシャはこの提案を受け入れ、エジプトにおける綿花の販売と輸出を独占することを認め後に他の作物よりも綿花を優先して栽培するように指示しました。1820年には俵3つ分しか収穫できませんでしたが、3年後の1823年には生産量は10,000トンにまで上がりました。このころからさらなる品質改善を求めて、新しい種子や栽培方法の改善が見直されました。今の ギザコットンで知られるギザ地域での栽培は、1827年のことです。ムハンマド・アリが、海島綿を輸入しギザ地域で栽培を試したところ今までにない高品質な綿ができギザコットンの栽培を成功させました。ナイル川沿いの肥沃な土と適度な湿度が上質な綿花を育てる条件に一致ギザコットンの栽培が繁栄しました。これが現在のエジプト超長綿の代名詞になるGIZAのベースになります。

19世紀初頭のムハンマド・アリー政権下のエジプトは、国民一人当たりの紡績機の数から見て、世界で5番目に生産性の高い綿花産業を持っていました。この産業は当初、動物の力、水車、風車などの自然エネルギー源に依存で駆動していました。19世紀初頭にエジプト綿花産業にも蒸気機関が導入され、1860年代のアメリカ南北戦争の頃には年間輸出額は1600万ドル(12万俵)に達し、1864年には5600万ドルに増加しました。これは主に世界市場における米国南部連合の供給が失われたためでした。その後輸出は有給労働者によって生産されるようになったアメリカ綿の再導入後も伸び続けエジプトの輸出は1903年には年間20万俵に達しました。

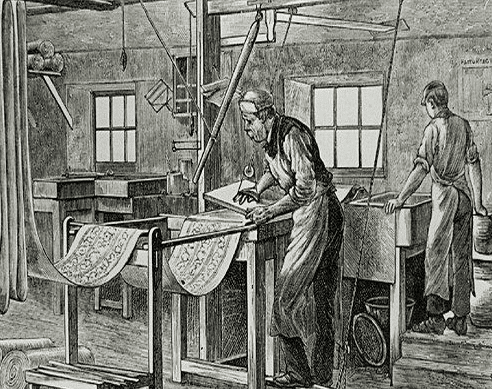

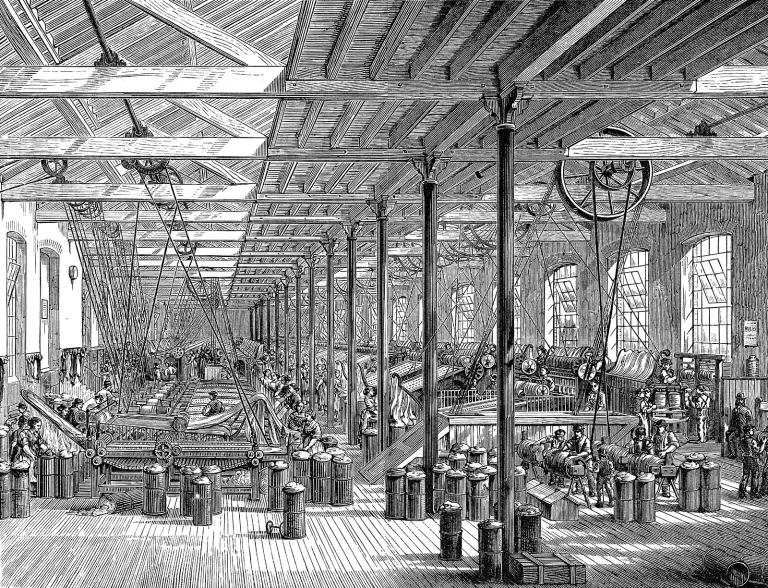

Seeing the East India Company and their textile importation as a threat to domestic textile businesses, Parliament passed the 1700 Calico Act, blocking the importation of cotton cloth. As there was no punishment for continuing to sell cotton cloth, smuggling of the popular material became commonplace. In 1721, dissatisfied with the results of the first act, Parliament passed a stricter addition, this time prohibiting the sale of most cottons, imported and domestic (exempting only thread Fustian and raw cotton). The exemption of raw cotton from the prohibition initially saw 2 thousand bales of cotton imported annually, to become the basis of a new indigenous industry, initially producing Fustian for the domestic market, though more importantly triggering the development of a series of mechanised spinning and weaving technologies, to process the material. This mechanised production was concentrated in new cotton mills, which slowly expanded until by the beginning of the 1770s seven thousand bales of cotton were imported annually, and pressure was put on Parliament, by the new mill owners, to remove the prohibition on the production and sale of pure cotton cloth, as they could easily compete with anything the EIC could import.

■ Cotton grown in India and Egypt though, was used widely throughout the rest of the world.

■ British woolen manufacturers were very concerned about the excessive trading in cotton and were keen to maintain their dominant market share of cloth manufacture

■ The Calico Act was passed in 1721 forbidding the importation of Calico cotton cloth from India.

■ The political forces whose interests converged on cotton as the cheaper cloth helped get this act repealed by 1774.

■ During these 50 years the British cotton industry developed without foreign competition.

The acts were repealed in 1774, triggering a wave of investment in mill-based cotton spinning and production, doubling the demand for raw cotton within a couple of years, and doubling it again every decade, into the 1840s.Indian cotton textiles, particularly those from Bengal, continued to maintain a competitive advantage up until the 19th century. In order to compete with India, Britain invested in labour-saving technical progress, while implementing protectionist policies such as bans and tariffs to restrict Indian imports. At the same time, the East India Company’s rule in India contributed to its deindustrialization, opening up a new market for British goods, while the capital amassed from Bengal after its 1757 conquest was used to invest in British industries such as textile manufacturing and greatly increase British wealth. British colonization also forced open the large Indian market to British goods, which could be sold in India without tariffs or duties, compared to local Indian producers who were heavily taxed, while raw cotton was imported from India without tariffs to British factories which manufactured textiles from Indian cotton, giving Britain a monopoly over India’s large market and cotton resources.India served as both a significant supplier of raw goods to British manufacturers and a large captive market for British manufactured goods..

Britain eventually surpassed India as the world’s leading cotton textile manufacturer in the 19th century.India’s cotton-processing sector changed during EIC expansion in India in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. From focusing on supplying the British market to supplying East Asia with raw cotton. As the Artisan produced textiles were no longer competitive with those produced Industrially, and Europe preferring the cheaper slave produced, long staple American, and Egyptian cottons, for its own materials

イギリス東インド会社とその織物の輸入を国内の繊維産業(主にウールやリネン)の脅威と考えた議会は、1700年にキャラコ法を制定し海外生産の綿布の輸入を禁止しました。しかし加熱したキャリコブームは綿布を売り続けても罰せられないため密輸が日常的に行われるようになっていました。1721年最初の法律の結果に不満だった議会は今度はより厳しい追加法を可決、輸入・国内を問わずほとんどの綿布の販売を禁止しました(”ファスティアン(=緯糸に綿、経糸には羊毛の綾織り)”と原綿だけは免除になりました)。キャラコを欲する国民は多く存在しており、キャラコに似た綿布であるファスティアンは引き続き大きなブームとなります。当初原綿は年間2,000俵が輸入されこれが新しい国産産業の基礎として発展し当初は国内市場向けに代替商品としてファスティアンを生産していましたが、ここでより重要な点は、この素材を加工するための一連の作業が需要を満たすために機械化されていき、紡織技術の開発の引き金となったことです(産業革命)。この機械化された生産は新しい製綿工場に集中、徐々に拡大していき、1770年代初めには年間7000俵の綿花が輸入されるようになりました。機械化で英国東インド会社がアジアから輸入するものと容易に競合できる純綿布の生産と販売が可能になった事で禁止を解除するよう新しい製綿工場の所有者が議会に圧力をかけ始めました。

キャラコ法とは何だったのか?

■ インドやエジプトで栽培された綿花は、世界各地で広く使われていた。

■ 英国の毛織物工場は綿花の過剰な取引に危機感を抱き布地製造における圧倒的なシェアを維持することを強く望んでいました。

■ 1721年インドからのキャラコ綿布の輸入を禁止する「キャラコ法」が制定されました。

■ 1721年にインドからキャラコ綿布の輸入を完全に禁止するキャラコ法が制定されました。

■ この50年間、イギリスの綿花産業は外国との競争にさらされることなく発展してきた。

1721年に制定された「キャラコ法」には、「ファスティアン」を禁制から除外する重要な抜け穴があった。ファスティアンとは、キャリコのように見える粗い羊毛と綿布の綾織り生地のことである

18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけてのイギリス東インド会社のインド進出によりインドの綿花加工部門は大きく変化していきます。イギリス市場への供給中心から東アジアへの原綿供給へと変化しました。ほぼ手作業で行われていた職人が生産する織物は工業的な織物に対して競争力を全く失いインドの綿布産業は壊滅的なダメージを負いました。その後ヨーロッパ諸国は安価な奴隷生産で産業を発展させてきた新興国のアメリカ超長綿やエジプト超長綿を自国の材料として好んで使用するようになっていきます。

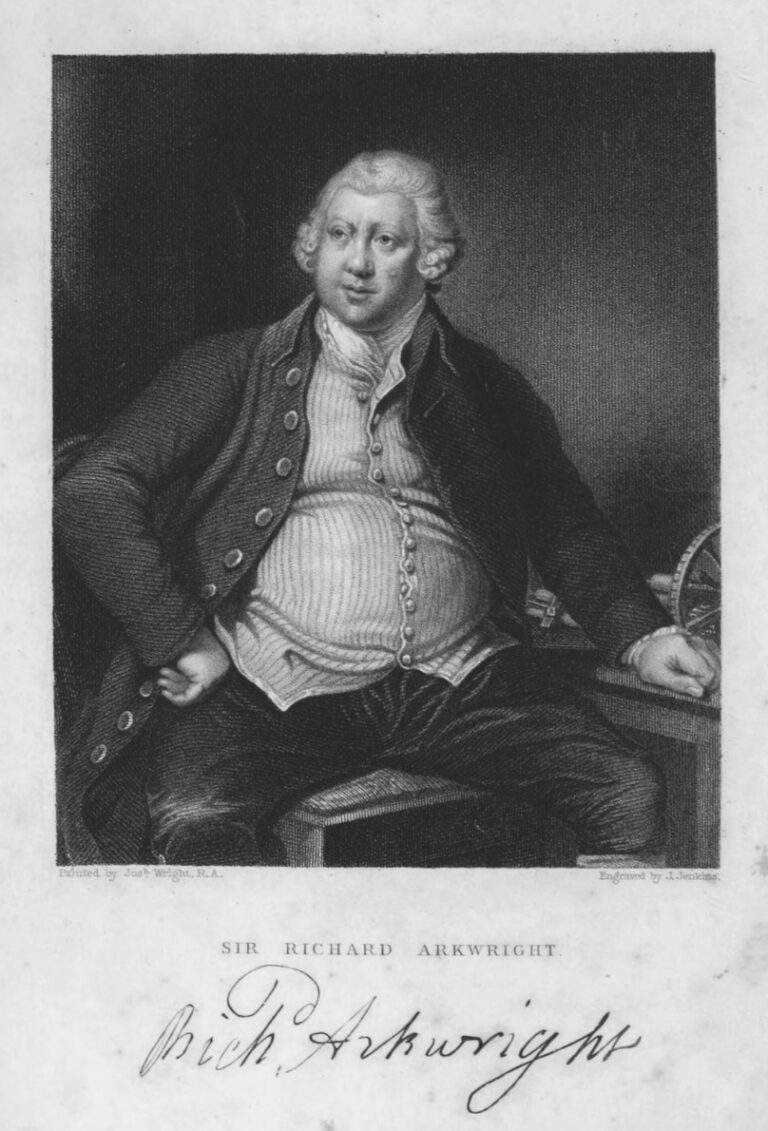

Production capacity in Britain and the United States was improved by the invention of the modern cotton gin by the American Eli Whitney in 1793. Before the development of cotton gins, the cotton fibers had to be pulled from the seeds tediously by hand. By the late 1700s, a number of crude ginning machines had been developed. However, to produce a bale of cotton required over 600 hours of human labor, making large-scale production uneconomical in the United States, even with the use of humans as slave labor. The gin that Whitney manufactured (the Holmes design) reduced the hours down to just a dozen or so per bale. Although Whitney patented his own design for a cotton gin, he manufactured a prior design from Henry Odgen Holmes, for which Holmes filed a patent in 1796.Improving technology and increasing control of world markets allowed British traders to develop a commercial chain in which raw cotton fibers were (at first) purchased from colonial plantations, processed into cotton cloth in the mills of Lancashire, and then exported on British ships to captive colonial markets in West Africa, India, and China (via Shanghai and Hong Kong).

1.英国人はインド人労働者が摘み取った畑のインド綿を専売制度により1日7セントで購入します。

2.この綿花はインド洋を渡り紅海を下り地中海を渡りジブラルタルを経てビスケー湾を渡り大西洋を渡ってロンドンまで3週間の船旅を経て英国船で輸送されます。

3. 綿花はランカシャーで綿布にされます。労働者には英国シリングの賃金を支払います。英国の労働者は賃金が良いだけでなく英国の鉄鋼会社は工場や機械を作成することで利益を得ています。賃金、利益、これらはすべて英国国内で消費されます。

4. 完成した製品は再び英国船でインドに送り返されます。この船の船長、士官、船員は英国人です。そこで利益を得るインド人は1日数セントで船上で汚れ仕事をする数人の下僕だけです。

5.布は最終的にインドの王や地主に売られます。地主は1日7セントで働くインドの貧民からこの高価な布を買うお金を得ているのです。

The cotton industry in the United States hit a crisis in the early 1920s. Cotton and tobacco prices collapsed in 1920 following overproduction and the boll weevil pest wiped out the sea island cotton crop in 1921. Annual production slumped from 1,365,000 bales in the 1910s to 801,000 in the 1920s. In South Carolina, Williamsburg County production fell from 37,000 bales in 1920 to 2,700 bales in 1922 and one farmer in McCormick County produced 65 bales in 1921 and just 6 in 1922. As a result of the devastating harvest of 1922, some 50,000 black cotton workers left South Carolina, and by the 1930s the state population had declined some 15%, largely due to cotton stagnation. Although the industry was badly affected by falling prices and pests in the early 1920s, the main reason is undoubtedly the mechanization of agriculture in explaining why many blacks moved to northern American cities in the 1940s and 1950s during the “Great Migration” as mechanization of agriculture was introduced, leaving many unemployed.