半分解展

The DEMI DECONSTRUCTION

1740: The War of the Austrian Succession breaks out, with Austria, Great Britain, and the Dutch Republic facing off against France, Prussia, and Spain.

1741: Prussia invades Silesia, a territory belonging to Austria, marking the beginning of the Silesian Wars.

1743: King Louis XV of France begins to rule directly.

1744: Maria Theresa’s husband Franz I acceded to the throne as Holy Roman Emperor.

1745: Bonnie Prince Charlie(Charles Edward Stuart) leads a rebellion in Scotland against the rule of George II of Great Britain, but is ultimately defeated at the Battle of Culloden.

1747:Ahmad Shah Durrani founded the Durrani dynasty in Afghanistan

1748: The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ends the War of the Austrian Succession, restoring the status quo ante bellum.

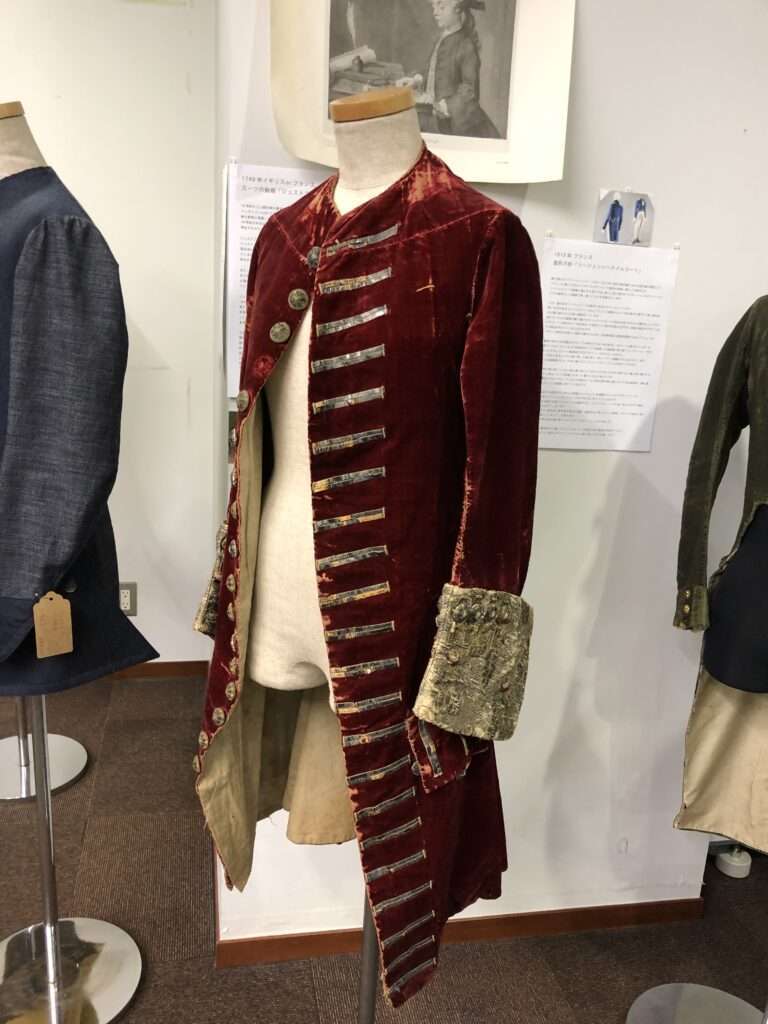

Early life (1630-1649):

▪️ Charles II was born on May 29, 1630, in St. James’s Palace in London.

▪️ He was the eldest son of King Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria.

▪️ Charles II spent his early years in the royal court, receiving a classical education from various tutors.

▪️ In 1642, the English Civil War broke out, and Charles II became a political pawn in the conflict between his father and the Parliamentarians.

Exile (1649-1660):

▪️ In 1649, Charles I was executed by the Parliamentarians, and Charles II fled to France, where he lived in exile for the next 11 years.

▪️ During his time in exile, Charles II made several unsuccessful attempts to regain the throne, including the ill-fated uprising of 1651 led by Charles II’s Scottish supporters.

Restoration (1660-1685):

▪️ In 1660, following the death of Oliver Cromwell and the collapse of the Commonwealth, Charles II was restored to the throne of England.

▪️ During his reign, Charles II presided over a period of relative political stability and economic growth.

▪️ Charles II was involved in several foreign policy challenges, including the Second and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars.

▪️ He was a patron of the arts and sciences, supporting the Royal Society and promoting the work of writers such as John Dryden and Samuel Pepys.

▪️ Charles II had a complex personal life, with numerous mistresses and illegitimate children. He had no legitimate children with his wife, Catherine of Braganza.

▪️ Charles II died on February 6, 1685, and was succeeded by his brother James II.

Charles II’s fashion choices were shaped by three main cultural factors. Firstly, the influence of his parents played a significant role. His father, James I, united England and Scotland in 1603, although the two countries retained separate parliaments until 1707. As a result, Charles II was technically the king of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and his coronation as such occurred on separate occasions. He was brought up as his father’s heir and dressed in elegant court attire, following his father’s example. Charles II’s French mother, Henrietta Maria, brought Parisian taste to the English court when she married Charles I in 1625. Even after fleeing England in 1644, she returned briefly when her son was crowned king in 1660. The influence of French court culture can be seen in various aspects of Charles II’s reign, but was particularly significant in the adoption of the royal lever and coucher, which involved the dressing and undressing of the king.

Secondly, Charles II’s fourteen years of exile from 1646 to 1660 had a profound impact on his fashion choices. During this time, he lived as an itinerant, often unwanted visitor, frequently short of money, clothes, and friends, and often doubting whether he would ever return to England or become king. He experienced court life in various countries, including France, Scotland, the Spanish Netherlands, and the United Provinces, as well as several cities in the Holy Roman Empire, such as Aachen, Cologne, and Spa. This gave him a cosmopolitan view of clothes and court culture, but one that was strongly influenced by French fashion and taste.

Finally, the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660 marked a significant turning point for Charles II’s fashion choices. With the revival of the royal household and ceremonial, there was a renewed focus on attire and image. However, it was not a complete return to the fashion of his father’s court prior to the civil war (1641-1651). Rather, it was a blend of old and new, with elements of French fashion and court culture mixed with traditional English styles. Charles II’s clothing choices reflected this mix, with him favoring the simpler coat, vest, and breeches, which became the forerunner of the modern three-piece suit. He also wore other types of clothing on specific occasions, allowing him to project different aspects of his personality and reinforce his authority.

Overall, Charles II’s clothing choices were carefully considered and reflected the influences of his upbringing, his experiences during exile, and the changing trends of his time. His fashion choices played a significant role in projecting his image as a powerful and fashionable monarch, and his legacy can still be seen in modern men’s fashion today.

During Charles II’s reign, his clothing was carefully planned and designed by a team of skilled craftsmen and suppliers. The yeoman of the robes placed annual orders with the Great Wardrobe, a sub-department of the king’s household responsible for purchasing silks and linens in bulk for royal use. The king’s tailor would then use these materials to make the king’s outer garments, while his seamstress would make his shirts, nightshirts, and other linen items.The creation of the king’s image was a collaborative effort between the monarch and his team of tailors, embroiderers, pinkers, and a wide range of specialist craftsmen and suppliers. Of these, the king’s tailors were among the most influential in shaping his image. Claude Sourceau and John Allen worked in partnership from 1660, and Sourceau continued to serve the king for a decade once he became king, followed by William Watt from 1672 and Robert Graham from 1678. Sourceau was particularly significant because he had served Charles II while he was in exile in France in the late 1640s and knew his taste very well.

One example of the close collaboration between Charles II and his tailor can be seen in a letter the king wrote to Minette from Breda on 29 April 1660, in which he noted that “I have sent to Gentseau to order some summer clothes, and I have told him to take the ribbons to you, for you to choose the trimmings and feathers.” Sourceau was able to tell Charles II about Paris fashions, while his partnership with Englishman John Allen from 1660 ensured that a network of suppliers and craftsmen, some of whom had been in exile with the king or had served his father, were involved in the production of the new king’s wardrobe.

In addition to the influence of his tailors, other cultural factors also impacted Charles II’s clothing choices. The influence of his parents was significant, with his French mother, Henrietta Maria, bringing Parisian taste to the English court when she married Charles I in 1625. During his fourteen years in exile from 1646 to 1660, Charles II experienced court life in France, Scotland, the Spanish Netherlands, and the United Provinces, as well as a number of cities in the Holy Roman Empire, giving him a cosmopolitan view of clothes and court culture.Finally, the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660 saw the revival of the royal household and royal ceremonial, but it was not a complete return to how things had been at his father’s court prior to the civil war. Despite this, Charles II’s clothing choices played an important role in creating a sense of continuity with the past, as well as projecting an image of power and authority that was necessary for his reign.

Secondly, Charles II’s fourteen years of exile from 1646 to 1660 had a profound impact on his fashion choices. During this time, he lived as an itinerant, often unwanted visitor, frequently short of money, clothes, and friends, and often doubting whether he would ever return to England or become king. He experienced court life in various countries, including France, Scotland, the Spanish Netherlands, and the United Provinces, as well as several cities in the Holy Roman Empire, such as Aachen, Cologne, and Spa. This gave him a cosmopolitan view of clothes and court culture, but one that was strongly influenced by French fashion and taste.

Finally, the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660 marked a significant turning point for Charles II’s fashion choices. With the revival of the royal household and ceremonial, there was a renewed focus on attire and image. However, it was not a complete return to the fashion of his father’s court prior to the civil war (1641-1651). Rather, it was a blend of old and new, with elements of French fashion and court culture mixed with traditional English styles. Charles II’s clothing choices reflected this mix, with him favoring the simpler coat, vest, and breeches, which became the forerunner of the modern three-piece suit. He also wore other types of clothing on specific occasions, allowing him to project different aspects of his personality and reinforce his authority.

On an annual basis, Charles II would order approximately thirty to forty new suits, single garments, or sets of garments from his tailors. However, his tailors also had to handle some repairs and alterations. For instance, in 1663-64, Sourceau and Allen received payment of 24 shillings for changing the garniture of four serviceable suits, 30 shillings for stitching buttons onto six knitted waistcoats, and 16 shillings for altering the linings of two cloaks. The king’s clothes were not only of social value but also held financial value, making them valuable perquisites. The diarist Samuel Pepys provided a glimpse into this process in his diary, where he described how the grooms of the bedchamber took the king’s linen as their fees at the end of each quarter. This resulted in the officers of the wardrobe of the robes facing a shortage of the king’s body linen.

The need to replace the king’s linen annually was a costly affair, as exemplified by Dorothy Chiffinch, who charged £30 3s in 1672 for making eighteen day shirts, eighteen night shirts, and eighteen half shirts, six caps, and four dozen pocket handkerchiefs for the king. To make these items, Chiffinch utilized a percentage of the 437.5 ells of Holland provided by Benjamin Shute, a linen draper, to make six pairs of sheets, twelve pillow beres, eighteen day shirts, eighteen night shirts, eighteen half shirts, six night caps “for our person for the half year ended at Michelmas 1672” (£245 19s 6d), six pieces of cambric for pocket handkerchiefs (£18), and six yards of fine muslin to renew bands and make cravats (£3 6s). Although the regular replacement of the king’s linen strained his finances, it ensured that traditional court patronage continued to operate, which was an essential part of court life.

Edward is often referred to as the “Black Prince”. The first known source to use the sobriquet “Black Prince” was the antiquary John Leland in the 1530s or early 1540s (about 165 years after Edward’s death). Leland mentions the sobriquet in two manuscript notes in the 1530s or early 1540s, with the implication that it was in relatively widespread use by that date. In one instance, Leland refers in Latin to “Edwardi Principis cog: Nigri” (i.e., “Edward the Prince, cognomen: The Black”); in the other, in English to “the Blake Prince”.In both instances, Leland is summarising earlier works – respectively, the 14th-century Eulogium Historiarum and the late 15th-century chronicle attributed to John Warkworth – but in neither case does the name appear in his source texts. In print, Roger Ascham in his Toxophilus (1545) refers to “ye noble black prince Edward beside Poeters”; while Richard Grafton, in his Chronicle at Large (1569), uses the name on three occasions, saying that “some writers name him the black prince”, and elsewhere that he was “commonly called the black Prince”. Raphael Holinshed uses it several times in his Chronicles (1577); and it is also used by William Shakespeare, in his plays Richard II (written c. 1595; Act 2, scene 3) and Henry V (c. 1599; Act 2, scene 4). In 1688 it appears prominently in the title of Joshua Barnes’s The History of that Most Victorious Monarch, Edward IIId, King of England and France, and Lord of Ireland, and First Founder of the Most Noble Order of the Garter: Being a Full and Exact Account Of the Life and Death of the said King: Together with That of his Most Renowned Son, Edward, Prince of Wales and of Aquitain, Sirnamed the Black-Prince.

Amidst his exile, Charles II lacked the traditional symbols of kingship known as regalia. As a result, he relied heavily on his garter regalia, which likely explains his strong attachment to the Order after the Restoration. Although Charles II only wore his garter robes during the order’s feast days, he demonstrated his loyalty by displaying the embroidered garter badge on the sleeves of his coats and cloaks. The accounts for 1678-79 reveal that Robert Graham received payment for making a light-colored coat and breeches with the coat adorned with purple, gold, and silver ribbon, as well as William Rutlish and George Pinkney receiving payment for embroidering the coat order. In addition, Charles II ordered silk ribbons to hang his lesser George on, as evidenced by the accounts for 1678-79 which show Richard Cartwright supplying nine pieces of George ribbon at a cost of £ 5431.

Other significant days at court that were celebrated by the king include Maundy Thursday during the 1660s and the days when the king touched ‘for the king’s evil. Although the king’s clothing accounts do not mention specific clothing made for these events, it is likely that Charles II chose silk garments with embroidered and applied decoration from his wardrobe. On the other hand, the king’s observation of St. David’s day required the king’s embroiderer to make leeks for key members of the royal family. In 1662-63, Edmund Harrison made two “rich leeks embroidered with pearls, gold and coloured silk for the king and queen” and smaller, less ornate versions for other members of the family at a cost of £ 13 7s 4d33. While court ceremonial events were important to Charles II, his reign also saw a change in approach to court ceremonial. Less emphasis was placed on court ceremonial, and members of the court formed stronger links with entertainments in London. As a result, tradition was important for significant events such as the coronation and ceremonies associated with the opening of Parliament, but it was allowed to slip to suit a new image of the English monarch that was more appropriate for the political climate after the Restoration.

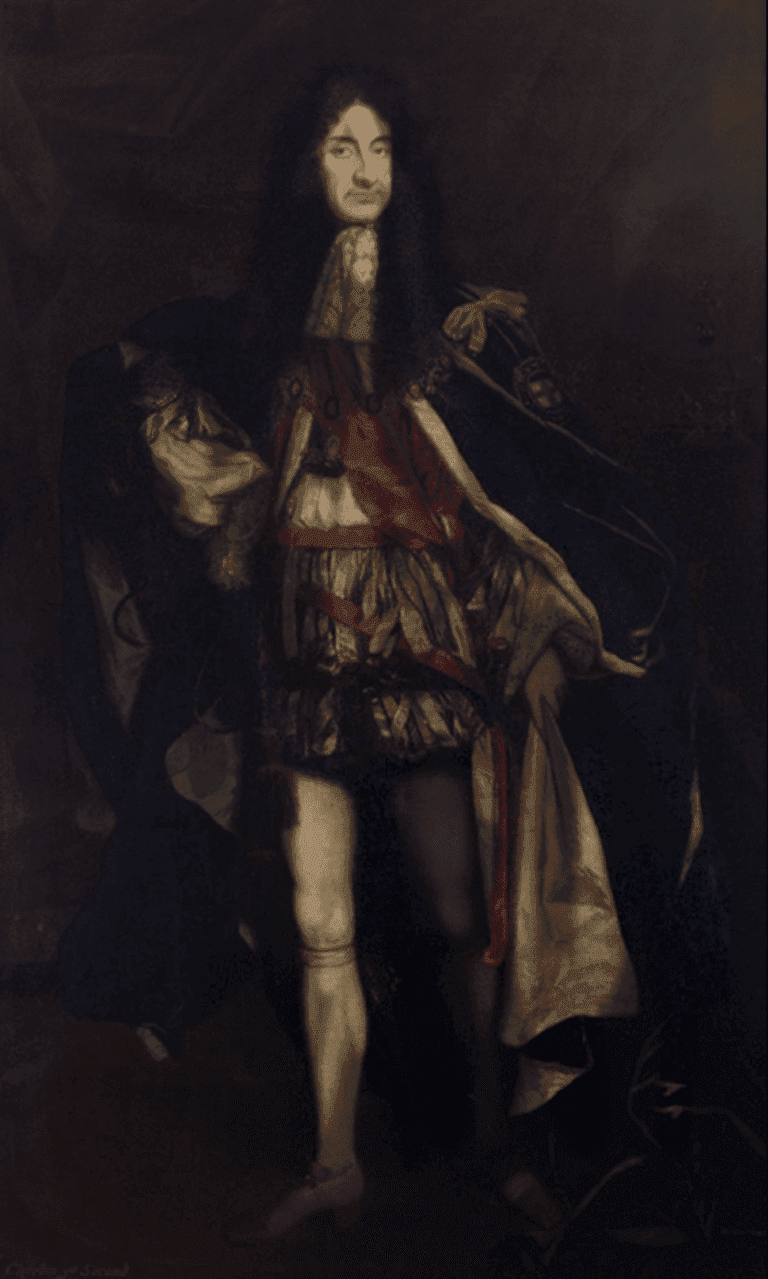

Charles II was inspired by the past while he brought changes to his court’s fashion compared to his father’s court. Charles I preferred doublets with full sleeves, waistline pointing down at the centre front with long tabs, which were worn with fairly full breeches. His son, on the other hand, wore a short doublet and petticoat breeches and gradually shifted to a coat, waistcoat, and breeches. While satin was the favored fabric at his father’s court, Charles II chose cloth, camlet, and silk velvet for his suits and coats, with striped, flowered, and brocaded silks for his waistcoats. Charles II is often linked with creating an English style – the vest – and rejecting French fashion. John Evelyn had criticized the English interest in French fashion in his pamphlet five years earlier. While the vest was novel, many researchers have questioned whether it was an original idea. The king’s ongoing influence from his French relatives is evident from his letters sent to his sister Minette. Charles II reverted to styles derived from the French court for his suits in the 1670s. However, his accounts indicate his preference for English wools, including Norwich stuffs.

Great Plague/pesto of London

Between 1665 and 1666, there was a major outbreak of the plague in Europe. This outbreak was brought to London by a Norwegian trading ship and quickly spread throughout the city, which was particularly vulnerable due to its narrow streets and poor hygiene.

The plague is a bacterial infection spread by infected fleas and symptoms include fever, headache, vomiting, and swelling of the lymph nodes. The plague is highly contagious and can become a fatal illness when it becomes severe.

In London, people were infected and died one after another, leading to a shortage of burial places and the accumulation of bodies. Medical facilities in the city became overloaded, and many doctors and nurses became infected with the plague and died. Furthermore, the plague hindered the movement of people within London and dealt a serious blow to commerce and trade.The Great Plague killed an estimated 100,000 people—almost a quarter of London’s population—in 18 months. The plague was caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, which is usually transmitted through the bite to a human by a flea or louse.

The outbreak of the plague was a very difficult time for London’s citizens. However, it came to an end due to another disaster, the Great Fire of London in 1666. The Great Fire burned the city, destroying many buildings and streets and causing many people to lose their homes. However, this fire destroyed many unsanitary buildings that were considered the cause of the plague, resulting in improved sanitation in the city. Additionally, after the Great Fire of London, buildings in the city were rebuilt with higher fire resistance, transforming the city into a more disaster-resistant urban area.

The Great Fire of London was a catastrophic event that occurred in 1666, causing significant damage to the city and altering its landscape forever. The fire began on September 2nd, 1666, in a bakery on Pudding Lane and quickly spread throughout the city, fueled by dry conditions and strong winds. Despite the efforts of firefighters and citizens, the fire raged for four days, consuming countless buildings and leaving the city in ruins.One of the main reasons the fire was so devastating was due to the lack of a coordinated response. The Lord Mayor, Sir Thomas Bloodworth, was slow to take action, and by the time he finally ordered the demolition of buildings to create firebreaks, the fire had already spread too far. This allowed the fire to continue its destructive path through the city, eventually destroying over 13,000 homes, 87 churches, and several significant landmarks, including St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The fire also had significant social and economic impacts. Many people were left homeless and without means to support themselves, leading to widespread poverty and hardship. As a result, many people fled the city, and those who remained struggled to rebuild their lives and the city around them.Despite the chaos and devastation caused by the Great Fire, there were also some positive outcomes. The fire helped to eliminate many of the city’s slums and unsanitary conditions, and it paved the way for the construction of new and improved buildings and infrastructure. Additionally, the fire prompted a renewed focus on fire prevention and firefighting techniques, leading to the creation of the first professional firefighting force in London.

The Great Fire of London had a significant impact on the reign of King Charles II. At the time of the fire, Charles was in Oxford, and upon receiving news of the disaster, he quickly returned to London to take charge of the relief efforts. During the aftermath of the fire, Charles worked to ensure that order was restored and that the city could be rebuilt. He ordered the demolition of buildings that were deemed unsafe, and he oversaw the creation of a plan for the reconstruction of the city. He also took steps to address the social and economic impacts of the fire, providing financial assistance to those who had lost their homes and encouraging people to stay in the city rather than fleeing to the countryside.

One of the challenges faced by Charles in the wake of the fire was the potential for social unrest. Many of the city’s residents were angry and frustrated, and there were concerns that this could lead to rebellion or even revolution. To prevent this, Charles took a number of steps to restore order, including suspending the writ of habeas corpus and authorizing the arrest and imprisonment of suspected troublemakers. Despite these measures, there were still many who were dissatisfied with the way that Charles handled the aftermath of the fire. Some felt that he had not done enough to prevent the disaster, while others criticized his response as heavy-handed and authoritarian. Nevertheless, Charles remained committed to rebuilding the city and restoring the confidence of its residents.

In the years that followed the Great Fire of London, Charles continued to oversee the reconstruction of the city, including the rebuilding of St. Paul’s Cathedral and the construction of new buildings and infrastructure. His efforts helped to transform London into a modern and vibrant city, and his reign is remembered as a time of great change and innovation in the history of England.

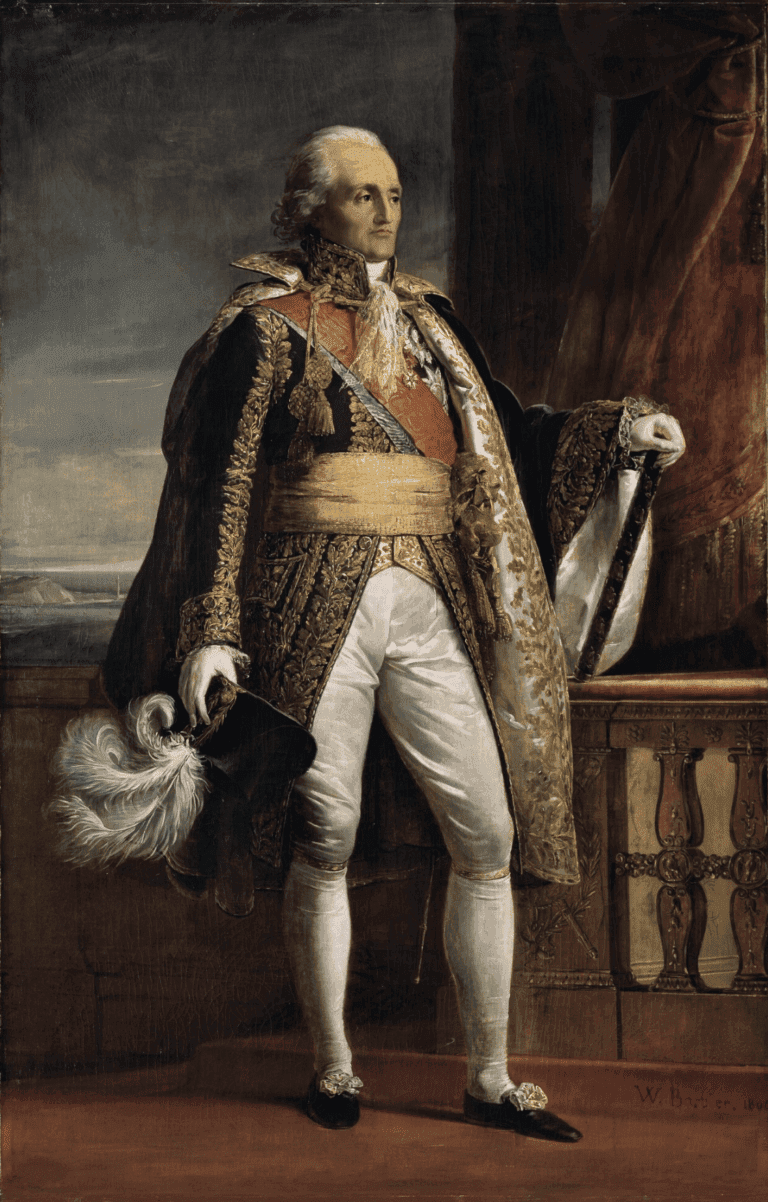

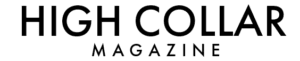

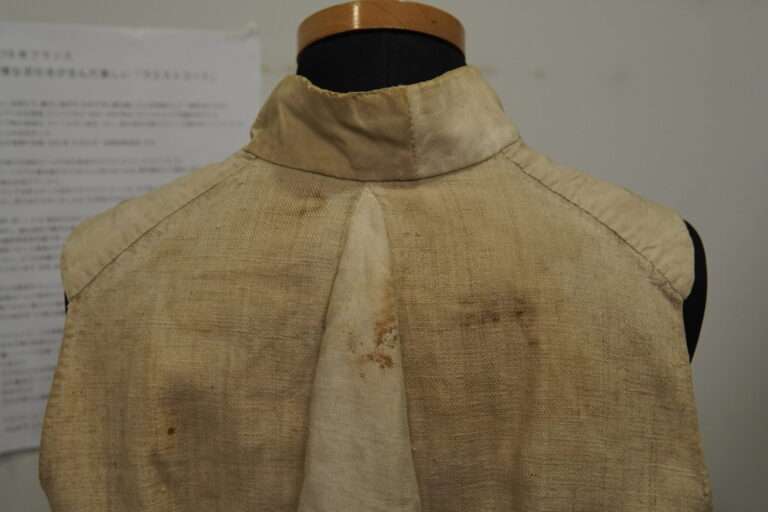

According to Susan Mokhberi, the justaucorps was modeled after a similar Persian coat with floral embroidery and a tight-fitting body and sleeves. Like Persian rulers who bestowed the coat on important subjects as a symbol of favor, King Louis XIV also used the justaucorps in the same way, and it became associated with French absolutism and the similarities between the Safavid and Bourbon absolutist regimes. As fashion trends changed over time, the fabric selection and style of the justacorps varied accordingly.

The Convention Parliament was dissolved in December 1660, and, shortly after the coronation, the second English Parliament of the reign assembled. Dubbed the Cavalier Parliament, it was overwhelmingly Royalist and Anglican. It sought to discourage non-conformity to the Church of England and passed several acts to secure Anglican dominance. The Corporation Act 1661 required municipal officeholders to swear allegiance; the Act of Uniformity 1662 made the use of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer compulsory; the Conventicle Act 1664 prohibited religious assemblies of more than five people, except under the auspices of the Church of England; and the Five Mile Act 1665 prohibited expelled non-conforming clergymen from coming within five miles (8 km) of a parish from which they had been banished. The Conventicle and Five Mile Acts remained in effect for the remainder of Charles’s reign. The Acts became known as the Clarendon Code, after Lord Clarendon, even though he was not directly responsible for them and even spoke against the Five Mile Act.

The Restoration was accompanied by social change. Puritanism lost its momentum. Theatres reopened after having been closed during the protectorship of Oliver Cromwell, and bawdy “Restoration comedy” became a recognisable genre. Theatre licences granted by Charles required that female parts be played by “their natural performers”, rather than by boys as was often the practice before; and Restoration literature celebrated or reacted to the restored court, which included libertines such as John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester. Of Charles II, Wilmot supposedly said:

We have a pretty, witty king,

Whose word no man relies on,

He never said a foolish thing,

And never did a wise one

To which Charles is reputed to have replied “that the matter was easily accounted for: For that his discourse was his own, his actions were the ministry’s”.

For a hat he prefers the Buckingamo or Montero , the Band or Cravat something soft , and so on .

Evelyn corrected this brochure for a second edition , and added the following note :

” Note that this was published two years before the Vest , Cravatt , Garters and Boucles came to be the fashion and therefore might haply give occasion to the change that ensued in those very particulars . “

The entry in the diary describing the sudden change of fashion is dated 18th October , 1666 .

” To court . It being the first time His Majesty put himself solemnly into the Eastern fashion of vest , changing doublet , stiff collar , bands and cloak , into a comely dress , after the Persian mode , with girdles or straps , and shoe – strings and garters into buckles , of which some were set with precious stones , resolving never to alter it , and to leave the French mode , which had hitherto obtained to our great expense and reproach . Upon which , divers courtiers and gentlemen gave His Majesty gold by way of wager that he would not persist in this resolution . I had sometime before presented an invective against that unconstancy , and our so much affecting the French fashion , to His Majesty ; in which I took occasion to describe the comeliness and usefulness of the Persian clothing , in the very same manner His Majesty now clad himself . This pamph let I entitled Tyrannus , or the Mode , and gave it to the King to read . I do not impute to this discourse the change which soon happened , but it was an identity that I could not but take notice of . “

The present cathedral was built by order of King Charles II over a period of 35 years from 1675. It was designed by Christopher Wren and features a large dome and two towers on the western facade, with dimensions of 157 m long, 74 m wide and 111 m high. It is considered a masterpiece of the Baroque style.

In 1661, five years prior to the devastating fire of 1666, Wren began providing counsel on the restoration of the Old St Paul’s. His proposal involved both interior and exterior upgrades to enhance the classical facade originally conceived by Inigo Jones in 1630. Wren envisioned replacing the worn-out tower with a dome, utilizing the existing framework as a scaffold. He created a sketch of the dome plan, which demonstrated his notion that it should stretch across the nave and aisles at the crossing.

After the fire, there was optimism that a significant portion of the old cathedral could be saved, but ultimately the entire edifice was torn down in the early 1670s. In July 1668, Dean William Sancroft contacted Wren, stating that he had been tasked by the Archbishop of Canterbury, in conjunction with the Bishops of London and Oxford, to formulate a design for a new cathedral that would be “Handsome and noble to all the ends of it and to the reputation of the City and the nation.” The design process lasted several years, but eventually, a plan was approved and attached to a royal warrant, with the caveat that Wren could make any further changes he deemed necessary.

The outcome was the current St Paul’s Cathedral, still the second largest church in Britain, with a dome declared as the finest in the world. The construction was financed by a coal tax and was completed during Wren’s lifetime, with many of the primary contractors employed for the duration.

According to Samuel Peeps, who recorded his diary, waistcoats began to be worn in place of coats in 1666 Oct 17. He wrote in his diary on that date that.

“The Court is all full of vests; only my Lord St. Albans not pinked, but plain black – and they say the King says the pinking upon white makes them look too much like magpies, and therefore hath bespoke one of plain velvet.”

Charles II was keenly aware that the waistcoat had become a fashion item expressing British uniqueness and declared that he would ‘never change’ its style. The waistcoat later became a very popular garment in Britain and was worn by many.

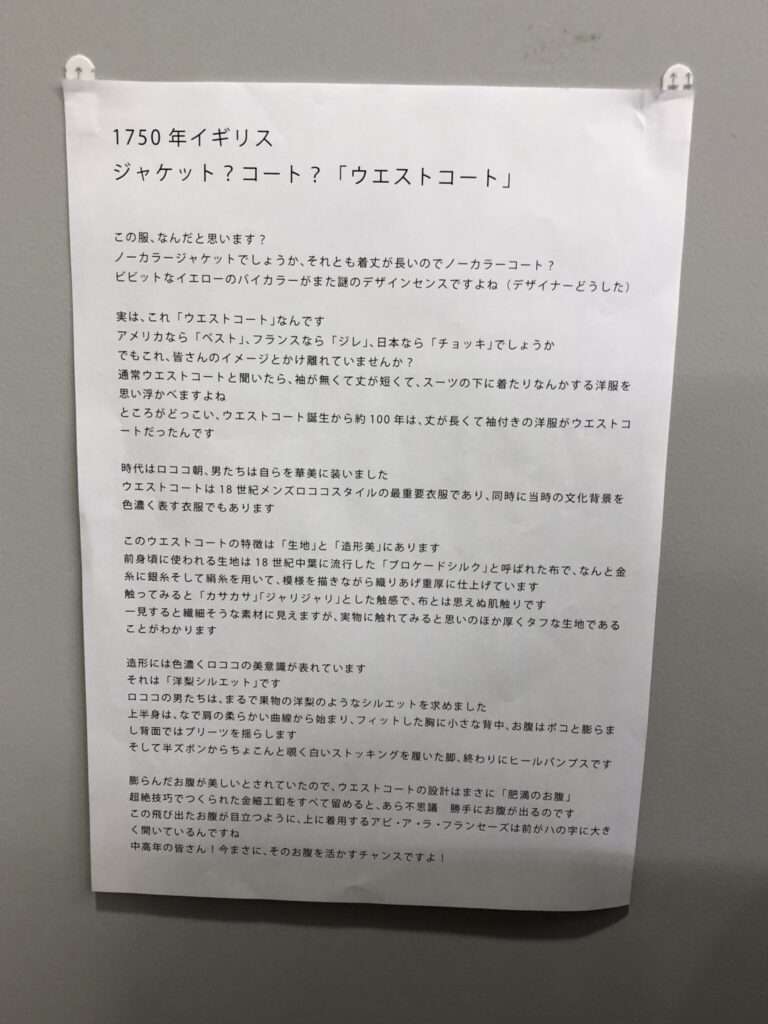

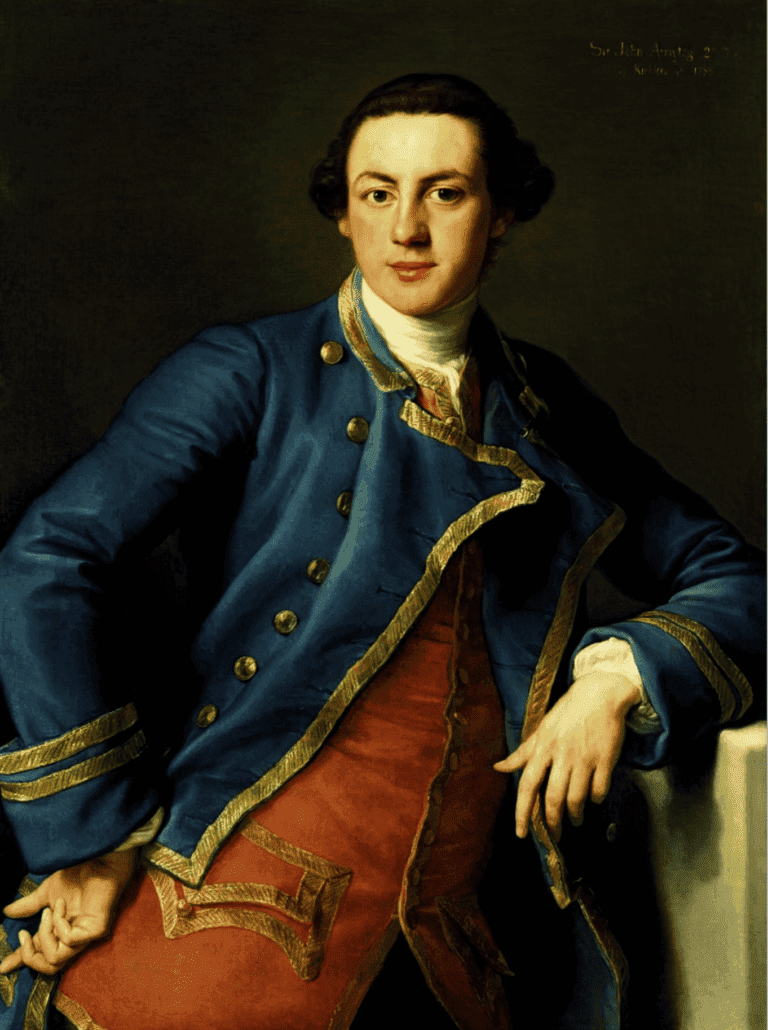

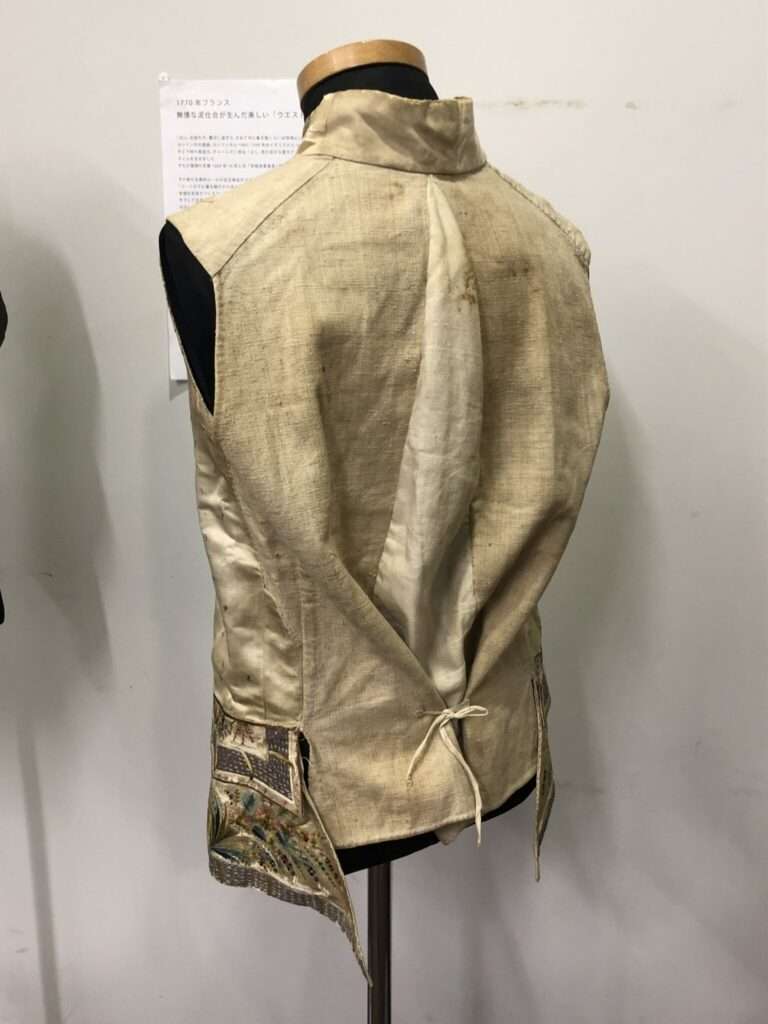

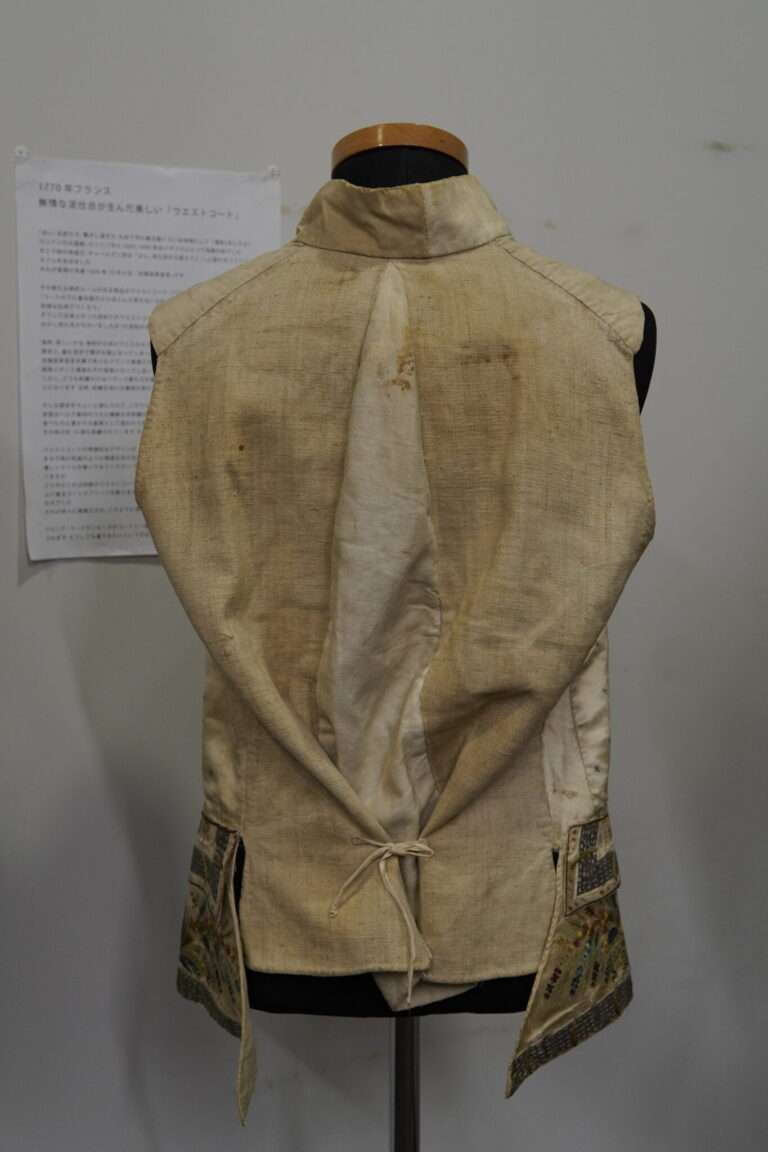

The Rococo fashion trend was characterized by opulence, elegance, refinement, and ornamentation. In contrast to the seventeenth-century women’s fashion, the eighteenth-century fashion was more sophisticated and ornate, reflecting the true style of Rococo. This trend extended beyond the royal court and became popular in the salons and cafes of the rising bourgeoisie. The exuberant and playful style of decoration and design that we now know as ‘Rococo’ was referred to as le style rocaille, le style moderne, and le gout at that time.

The robe volante, a flowing gown with a bodice and large pleats flowing down the back to the ground over a rounded petticoat, gained popularity during the early eighteenth century, towards the end of King Louis XIV’s reign. The color palette was rich and dark, with elaborate and heavy design features. After Louis XIV’s death, fashion evolved into a lighter and more frivolous style, marking the transition from the baroque period to the well-known Rococo style. Pastel colors, more revealing frocks, and trims such as frills, ruffles, bows, and lace became popular.

The later period introduced the typical women’s Rococo gown, the robe à la Française, which had a tight bodice with a low cut neckline, large ribbon bows down the centre front, wide panniers, and lavish trims of lace, ribbon, and flowers. The Watteau pleats, named after the painter Jean-Antoine Watteau, became more popular, with gowns featuring intricate details down to the stitches of lace and other trimmings. The ‘pannier’ and ‘mantua’ also became fashionable, featuring wide hoops under the dress that extended the hips out sideways, becoming a staple in formal wear. These features originated from seventeenth-century Spanish fashion, initially designed to hide the pregnant stomach, and were later reimagined as the pannier.

1745 marked the Golden Age of the Rococo, with the introduction of an exotic and oriental culture in France known as a la turque, made popular by Louis XV’s mistress, Madame Pompadour. In the 1760s, a style of less formal dresses emerged, such as the polonaise, inspired by Poland, and the robe a l’anglais, incorporating elements inspired by male fashion. Accessories were also important, as they added to the opulence and decor of the body, with ladies required to wear gloves to cover their hands and arms at official ceremonies if their clothes were sleeveless.

Two ‘Incroyables’, so called because they, together with their female counterpart ‘the Merveilleuses’, dressed extravagantly as a rebellious group during the French Directoire (`1795-1799) . Left: ‘incroyable’ dressed in a frak, striped waistcoat and calf trousers. Cravate. Striped stockings. Accessories: earring in right ear, diamond brooch(?), walking stick, top hat, boots with pointed noses. Right: ‘incroyable’ dressed in a frak with large lapel and double row of buttons. Striped waistcoat and knee-length trousers. Striped cravate. Stockings. Accessories: stitch with coathanger, lorgnet in hand, earring in left ear, brooch(?) in the shape of a crescent moon, walking stick, flat shoes with pointed noses.