THE FIBER

You can search about the Fiber knowledge.

Text By KATS TANAKA

リネンは亜麻繊維から作られる植物系の織物で非常に丈夫であり、吸水性が高く綿よりも早く乾くという特徴があります。そのため、暑い季節でも快適に過ごすことができ衣料品として重宝されています。また繊維の性質上シワになりやすいという特徴もあります。

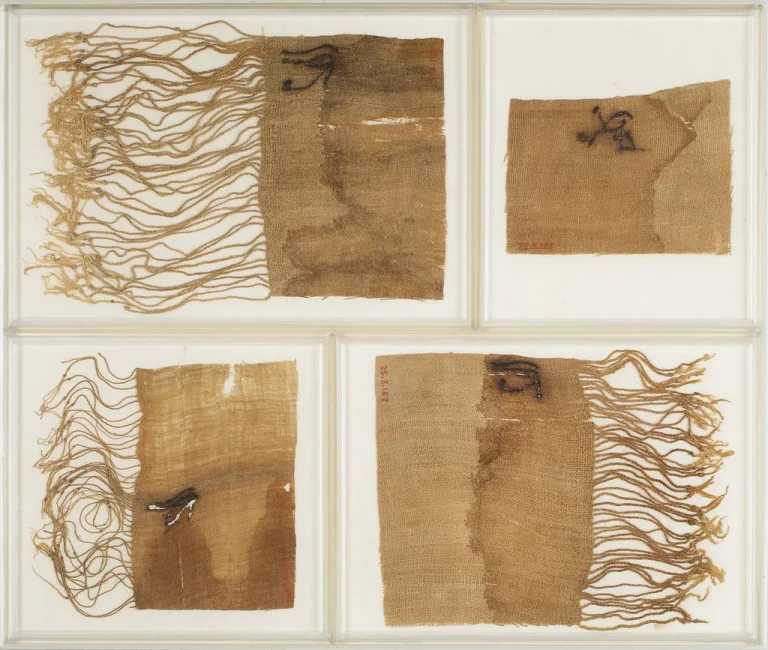

リネンの歴史は古く数千年前にまでさかのぼると言われています。ヨーロッパ南東部(現在のグルジア近辺)の洞窟で発見された染めた亜麻繊維は、野生の亜麻から織られたリネンが3万年以上前から使われていたことを示唆しています。メソポタミアや古代エジプトなどの古代文明でもリネンが使用され聖書にもリネンの記述があります。18世紀以降リネン産業はヨーロッパ各国やアメリカ植民地の経済にとって重要な役割を果たした。綿や麻など非麻の繊維を使ったリネン織りの織物も、大まかに「リネン」と呼ばれることもあります。

The world’s leading producers of linen are largely concentrated in Europe, with a few notable exceptions. Here are some of the top linen-producing countries and a brief history of their linen industries:

■ Belgium: Belgium has a long history of linen production, dating back to the Middle Ages. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Belgian linen became known for its high quality, and the country is still a major producer of linen today.

■ France: As I mentioned earlier, France has a rich history of linen production, with the industry dating back to ancient times. The linen produced in France is highly regarded for its quality and durability.

■ Ireland: The Irish linen industry began in the 17th century and quickly became one of the country’s most important industries. Irish linen is still highly sought after today for its fine texture and high quality.

■ Italy: Italy has been producing linen for centuries, with the industry centered mainly in the northern regions of the country. Italian linen is known for its softness and durability.

■ China: China is one of the world’s largest producers of linen, with a long history of linen production dating back to ancient times. Chinese linen is known for its high quality and competitive pricing.

■ India: India is also a major producer of linen, with a long history of textile production. Indian linen is known for its unique textures and patterns.

These countries, along with others such as Poland, Russia, and the United States, continue to produce high-quality linen that is used in a variety of products, including clothing, bedding, and home furnishings.

世界のリネン生産は、一部の例外を除きほとんどがヨーロッパに集中しています。リネンの主要生産国とは大きく分けて下記の国になります。

■ ベルギー ベルギーのリネン生産の歴史は古く、中世にさかのぼります。18~19世紀にはその品質の高さで知られるようになり、現在でも主要なリネン生産国です。

■ フランス リネン生産の歴史が古く、その歴史は古代に遡ります。フランスで生産されるリネンはその品質と耐久性で高い評価を得ています。

■ アイルランド アイルランドのリネン産業は17世紀に始まり瞬く間に国の重要な産業のひとつとなりました。現在もその上質な風合いと品質は高く評価されています。

■ イタリア イタリアでは何世紀にもわたりリネンの生産が行われており主に北部を中心に産業が行われています。柔らかさと耐久性が特徴です。

■ 中国 中国は世界有数のリネン生産国であり、リネン生産の歴史は古く古代までさかのぼります。中国産リネンは高品質で価格競争力があることで知られています。

■ インド インドもリネンの主要産地であり、繊維生産の長い歴史があります。インドのリネンは独特の風合いと柄で知られています。

このほか、ポーランド、ロシア、米国などでも高品質なリネンが生産され、衣類や寝具、インテリアなどさまざまな製品に使用されています。

リネンという言葉は西ゲルマン語起源で、亜麻のラテン語名linumや、それ以前のギリシャ語λινόν(リノン)と同義語です。この言葉の歴史は英語における他の多くの用語を生み出し、特にリネン(亜麻)の糸を使って直線を決めることからライン(line)が生まれました。また、リネンが衣服の内側に使われたことからライニング、元々リネンで作られた下着を意味するフランス語のランジェリーなど、他の多くの用語とも語源的に関係があります。

「古英語 līn「亜麻、リネン糸、リネン布」+-en から、「亜麻で作られた」形容詞 linen の名詞的用法、14世紀初頭。古英語 lin は原ゲルマン語 *linam (古サクソン語、古ノルド語、古高ドイツ語 lin 「亜麻、リネン」、ドイツ語 Leinen 「麻布」、ゴート語 lein 「麻布」の語源)、おそらくラテン語 linum 「亜麻、リネン」から早く借用したもので、ギリシャ語 linon とともに非インド・ヨーロッパ系言語からきていると思われます。しかし、中央ヨーロッパでの亜麻の栽培は非常に古くから行われていたので、原語との同一性はあり得ます。しかし、リノンとリヌムが地中海の言葉に由来する可能性はより高いです。インド・イラン語ではこの言葉は知られていない(しかし概念はもちろんある)。” リトアニア語のlinai、古教会スラブ語のlinu、アイルランド語のlinは、おそらく最終的にはラテン語かギリシャ語に由来するものと推察されます。

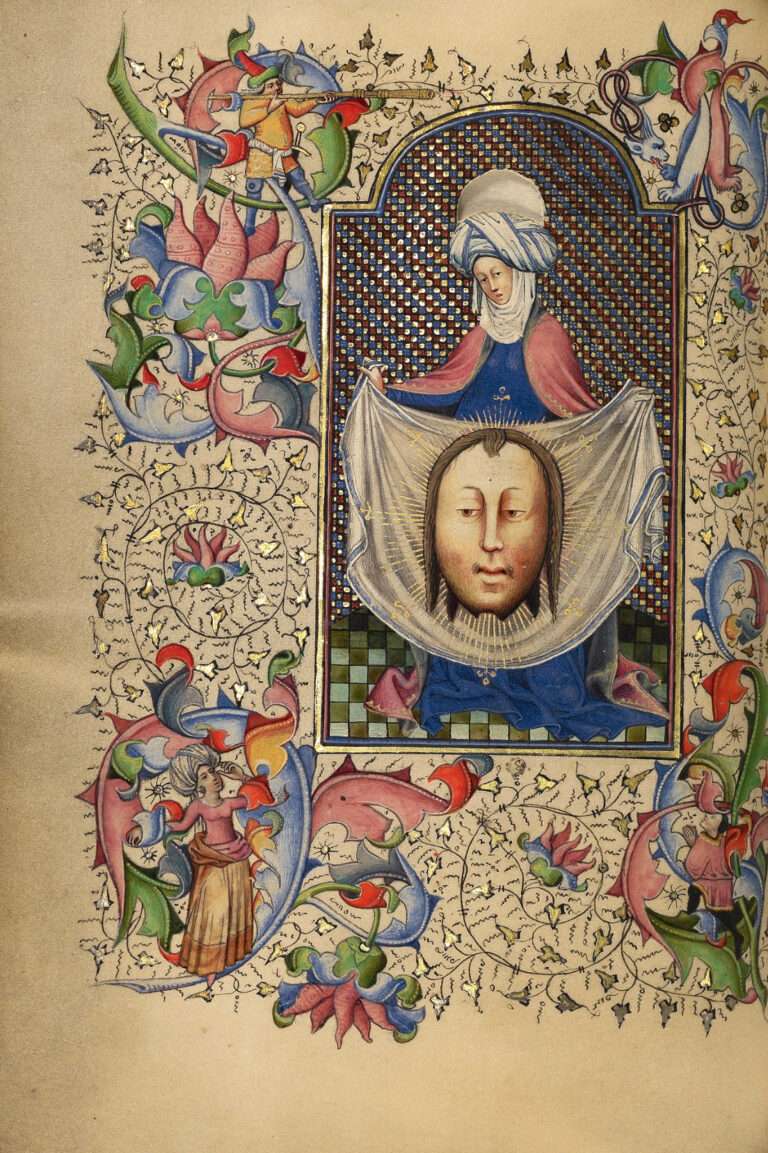

聖書にはリネンに関する記述が多く、人類の文化にリネンが深く浸透していることがうかがえます。ユダヤ教では、衣服に織り込んでよい布に関する唯一の律法はシャートネズと呼ばれるリネンとウールの混合に関するもので、申命記22章11節「汝、混じり合ったもの、ウールとリネンを共に着てならない」とレビ記19章19節「・・・2種類のものが混じり合った衣服は、あなたの上に着てならない」で制限されていました。1世紀のローマ・ユダヤ人の歴史家ヨセフスは、この禁止の理由を一般人が祭司の公式の衣服を身につけないようにするためだと示唆、中世のセファルディ系ユダヤ人の哲学者マイモニデスは、異教徒の祭司がそうした混ざった衣服を着ていたからだと考えています。 またこのような命令は実用的であると同時に寓意的な目的もあり、おそらくここでは暑い気候で不快感(または過剰な汗)を引き起こすような祭司の衣服を防ぐためであろうと説明する人もいます。リネンは聖書の箴言31章でも言及されており、高貴な妻を描写している箇所である。箴言31:22は”彼女は寝床に覆いを作り、上質の麻布と紫を身にまとう。”という記述があります。また、新約聖書では、上質な白いリネンは天使が身に着けています。

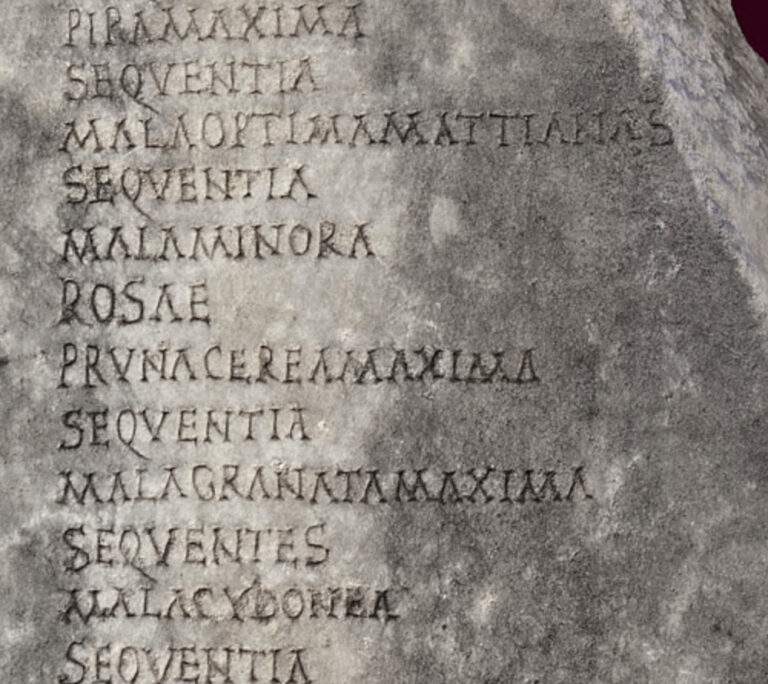

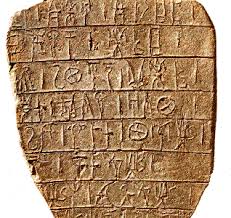

The earliest written documentation of a linen industry comes from the Linear B tablets of Pylos, Greece, where linen is depicted as an ideogram and also written as “li-no” (Greek: λίνον, linon), and the female linen workers are cataloged as “li-ne-ya” (λίνεια, lineia).

リネン産業に関する最古の文献はギリシャのピロスの『リニアBタブレット』でリネンは表意文字として描かれまた「リノ」(ギリシャ語:λίνον、リノン)と書かれ、女性のリネン労働者は「リネヤ」(λίνεια、ラインア)として目録に載せられています。

there was a thriving trade in German flax and linen. The trade spread throughout Germany by the 9th century and spread to Flanders and Brabant by the 11th century. The Lower Rhine was a center of linen making in the Middle Ages. Flax was cultivated and linen used for clothing in Ireland by the 11th century. Evidence suggests that flax may have been grown and sold in Southern England in the 12th and 13th centuries.Textiles, primarily linen and wool, were produced in decentralized home weaving mills.

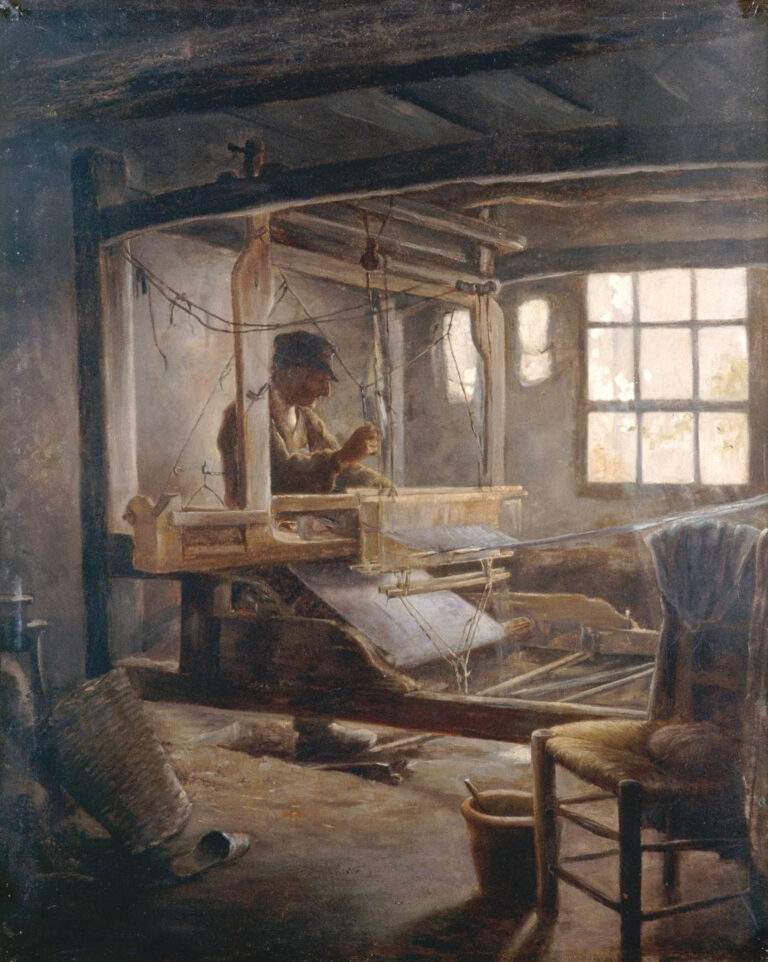

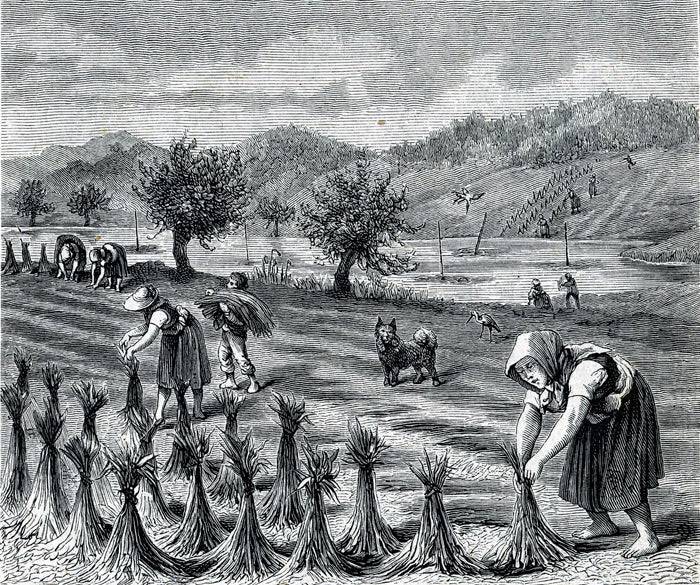

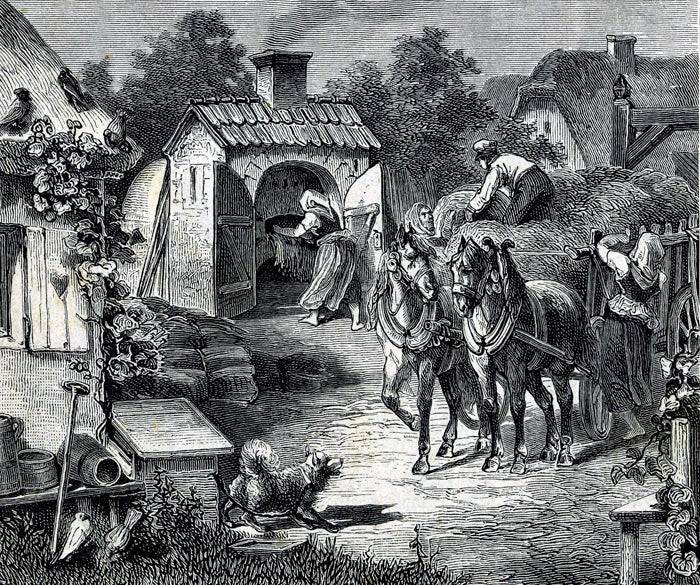

中世には亜麻が重要な役割を果たし、リネンは貴重な商業品となりました。ヨーロッパではリネン産業が盛んでした。ドイツでは、特にシレジア、ヴェストファーレン、アルザス、シュヴァーベンなどで盛んに行われていました。 ヨーロッパで最も裕福な一族となったフュッガー家の商業王朝はドイツの都市アウグスブルクのリネン貿易から始まりました。「富豪」と呼ばれたヤコブ・フッガーは織物職人の息子でした。 降水量の多いシュヴァーベンアルプの山々では、19世紀になっても亜麻が大量に栽培され、地元の農民の家で格別な価値を持つ布に織り上げられドイツの亜麻とリネンの交易が盛んに行われるようになりました。9世紀にはドイツ全土に広がり、11世紀にはフランドルやブラバントにも広まりました。ライン川下流域は中世のリネン製造の中心地でした。11世紀にはアイルランドで亜麻が栽培されリネンが衣服に使われるようになりました。12~13世紀には南イングランドで亜麻が栽培され販売されていた可能性があります。 リネンとウールを中心とした織物は、分散した家庭用織物工場で生産されていました。

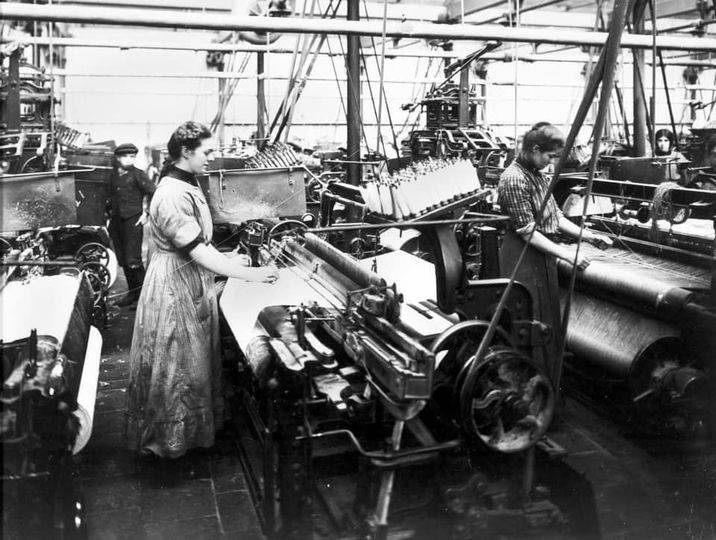

18世紀から19世紀にかけて、ヨーロッパの経済においてリネン産業はますます重要な位置を占めるようになりました。イギリスそしてドイツでは、工業化と機械生産が手作業に取って代わり生産は家庭から新しい工場に移っていきました。リネンはアメリカ植民地でも重要な製品で最初の入植者と共に持ち込まれ最も一般的に使用される織物となり植民地の家庭の貴重な財産となりました。 アメリカ独立戦争時においてのホームスパン運動は家庭で紡がれる織物を作るために亜麻を使うことを奨励しました。1830年代を通じてアメリカ北部のほとんどの農家は家族の衣類に使用するためにリネンのための亜麻を栽培し続けていました。19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてリネンはロシアとその経済にとって非常に重要な製品になりました。一時期は国の最大の輸出品目でありロシアは世界の繊維亜麻作物の約80%を生産していました。

789年にフランスのシャルルマーニュ王がすべての家庭で亜麻を栽培しリネン織物を織ることを命じます。リネン生産は家庭のものとなりました。この伝統は18世紀まで続き、衣類、ベッドリネン、家庭用テキスタイルはすべて家庭で作られるようになりました。その後、何世紀にもわたりリネンは多くの芸術作品の土台となります。11世紀のバイユーのタペストリーは征服王ウィリアムがイングランドのハロルド王から王冠を奪う様子を描いたもので70メートルのリネンを使って作られました。16世紀初頭フランドル地方の画家ピーター・ポール・ルーベンスの影響でヨーロッパの多くの芸術家が木版画からリネンキャンバスに移行し現在でもその人気は続いています。

There were several reasons why Huguenots were involved in the cultivation and production of linen:

■ Religion: Huguenots were French Protestants who faced persecution and discrimination in Catholic France. Many Huguenots were involved in industries such as linen production that were less controlled by the Catholic Church, as they provided a way to earn a living without facing religious discrimination.

■ Tradition: The cultivation of flax and the production of linen had been a part of French culture for centuries, and many Huguenots were familiar with the industry and had skills and knowledge that made them well-suited to work in it.

■ Innovation: Huguenots were known for their skills and innovation in a variety of industries, including linen production. Many Huguenot weavers brought with them new techniques and innovations that helped to advance the French linen industry and make it more competitive with other countries.

■ Geography: Many Huguenots settled in regions of France where linen production was already established, such as Normandy and Picardy. These regions had a long tradition of linen production and provided an ideal environment for Huguenots to continue their work in the industry.

Overall, the Huguenots’ involvement in the linen industry was driven by a combination of economic, social, and cultural factors, as well as their skills and knowledge in the field.

ユグノーがリネンの栽培・生産に携わるようになった理由はいくつかあります。

■ 宗教。宗教:ユグノーはフランスのプロテスタントで、カトリック国であるフランスで迫害と差別を受けていました。ユグノーの多くは、カトリック教会の支配が緩やかなリネン生産などの産業に従事し、宗教的な差別を受けることなく生計を立てることができたのできました。

■ 伝統 亜麻の栽培とリネンの生産は何世紀にもわたってフランスの文化の一部であり多くのユグノーがこの産業に精通し技術や知識を持っていたため、この産業で働くのに適していました。

■ 革新性。ユグノーはリネン製造を含むさまざまな産業において、その技術と革新性で知られていました。ユグノーの織物職人の多くは新しい技術やイノベーションを持ち込みフランスのリネン産業を発展させ、他国との競争力を高めるのに貢献しました。

■ 地理 ユグノーの多くは、ノルマンディーやピカルディなどリネン生産が盛んな地域に定住しました。これらの地域はリネン生産の長い伝統がありユグノーがリネン産業で仕事を続けるには理想的な環境でした。

ユグノーがリネン産業に携わった背景には、経済的、社会的、文化的な要因に加え、彼らの技術や知識の礎があったのです。

マルキニエとは、フランスのサルトリアの伝統と高い職人技を象徴するもので、リネン(亜麻布、リノン、バティスト)のみを使った高級織物を織り取引する技術です。マルキニエとは、織物デザイナー、織物職人、そしてキャンバスの商人を意味します。マルキニエは、ティセラン(手織り職人)であるだけでなく、自分たちの工芸品を販売する商人でもあった。この活動は農村の原産産業として主に村の中で発展したため、mulquiniersは自宅の地下室で「bahottes」や「blocures」から最適な湿度を得ながらmétiers à tisserに取り組んでいました。ミュルキネリーは、17世紀から18世紀にかけて、現在のオー・ド・フランス地方を構成するフランス北部諸県を起源とする。語源的には、「マルキニエ」はゲルマン語で「薄いキャンバス」を意味する「mollquin」に由来する。この用語の最初の痕跡は、1413年の「ヴァランシエンヌのマルキニエ憲章」の中で、「モルキニエ」という用語の使用を通じて確認できる。最も古いマルキニエの家系の中には、17世紀以降、染色家、織物作家、刺繍師、パターンメーカー、手紡ぎ師として活躍してきたレシーニュ家とルゲイル家系がある。

最も重要なことは、太陽王・ルイ14世のナントの勅令の廃止(フォンテーヌブローの勅令)によりプロテスタントを弾圧、これがフランスから産業の技術的な流出を招いたことである(20万人が海外へ流出したとされている)。しかしナント自体はこの後大西洋への黒人奴隷の中継貿易港としてスペイン・マルセイユと共に共に繁栄することになります。

Flemish linen has a long and rich history that dates back to the Middle Ages, when Flanders was one of the most prosperous and influential regions in Europe. The region that is now Flanders includes parts of modern-day Belgium, France, and the Netherlands, and has long been known for its flax cultivation and linen production.The earliest known evidence of linen production in Flanders dates back to the 11th century, and by the 12th and 13th centuries, Flanders had become a major center of linen production in Europe. The linen produced in Flanders was renowned for its quality and was highly prized by royalty, aristocrats, and the wealthy elite throughout the continent.

The production of Flemish linen was a complex and labor-intensive process that involved several stages. First, flax was grown and harvested, then the fibers were separated and processed through a process called retting, which involved soaking the flax in water to break down the fibers. The fibers were then spun into yarn and woven into fabric, which was finished and bleached to achieve the signature white color and smooth texture that was characteristic of Flemish linen. Flemish linen was used for a wide range of purposes, including clothing, bedding, table linens, and curtains. It was also used to create tapestries, which were a popular form of art and decoration in the Middle Ages.

The linen industry in Flanders reached its peak in the 16th and 17th centuries, when the region was part of the Spanish Netherlands. During this time, the linen industry was closely regulated by the government, and the quality of Flemish linen was maintained at a very high level. However, the industry began to decline in the 18th century, due in part to competition from other European countries.

There is a historical connection between the woollen and linen industries in the Flanders region. Both industries were important sources of wealth and employment in the region, and they often relied on similar resources and production techniques. For example, both industries relied on locally grown flax and wool as their primary raw materials. In addition, many of the tools and machines used in both industries were similar or interchangeable, such as spinning wheels and looms.

In some cases, textile workers in Flanders were skilled in both woollen and linen production, and would switch between the two industries depending on demand and market conditions. This was particularly true in the 16th and 17th centuries, when the region’s textile industry was at its peak. There was also some cross-pollination between the two industries in terms of design and style. For example, Flemish tapestries, which were often made from wool, were known for their intricate designs and vibrant colors, and some of these same design elements were used in linen production as well. The production of Flemish linen was a complex and labor-intensive process that involved several stages. First, flax was grown and harvested, then the fibers were separated and processed through a process called retting, which involved soaking the flax in water to break down the fibers. The fibers were then spun into yarn and woven into fabric, which was finished and bleached to achieve the signature white color and smooth texture that was characteristic of Flemish linen. Flemish linen was used for a wide range of purposes, including clothing, bedding, table linens, and curtains. It was also used to create tapestries, which were a popular form of art and decoration in the Middle Ages.

Belgium has a rich history of linen production, dating back thousands of years. The region’s temperate climate and fertile soil were well-suited for growing flax, the primary raw material used in linen production, and the area became known for the high quality of its linen fabrics. Linen production in Belgium began in earnest in the Middle Ages, with Flanders and Bruges becoming major centers of the industry. Flemish weavers were known for their skill in creating complex patterns and designs in their textiles, and their linen fabrics were highly sought after throughout Europe.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Belgium’s linen industry experienced a period of growth and expansion, thanks in part to the development of new techniques and machinery for processing flax and weaving linen. This period saw the emergence of large-scale linen factories, particularly in the Ghent and Courtrai regions, and the industry became an important source of employment and economic growth for the region. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Belgium’s linen industry faced increasing competition from other countries, particularly Ireland and Northern France. However, many Belgian linen producers continued to innovate and develop new techniques, and the industry remained an important part of the country’s economy.

Today, Belgium is still known for its high-quality linen fabrics, particularly in the area of home textiles and interior design. The country is home to a number of small-scale linen producers who use traditional techniques and high-quality materials to create beautiful, durable linen fabrics.

ベルギーのリネン生産の歴史は古く数千年前にさかのぼります。温暖な気候と肥沃な土壌は、リネンの主原料である亜麻の栽培に適しており、高品質のリネン織物として知られるようになりました。ベルギーのリネン生産は中世に本格化しフランドルやブルージュが一大生産地となりました。フランドル地方の織物職人は複雑な柄やデザインを織り込む技術に長けておりそのリネン織物はヨーロッパ中で高い人気を博した。17世紀から18世紀にかけて、ベルギーのリネン産業は、亜麻の加工やリネンを織るための新しい技術や機械の開発などにより、成長・拡大期を迎えます。この時期特にゲントやコートライ地方に大規模なリネン工場が出現しこの地域の雇用と経済成長の重要な源泉となりました。19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて、ベルギーのリネン産業は、他国、特にアイルランドや北フランスとの競争の激化に直面、しかしベルギーの多くのリネン生産者は技術革新を続け、新しい技術を開発しこの産業はベルギー経済の重要な部分を占め続けました。今日でもベルギーは、特にホームテキスタイルやインテリアデザインの分野で、高品質のリネンファブリックの産地として知られています。この国には小規模なリネン生産者が数多く存在し伝統的な技術と高品質な素材を用いて、美しく耐久性のあるリネンファブリックを生み出しています。

第二次世界大戦中、亜麻は貴重な原料でした。その強さから、軍用にとても便利な織物でした(トラックや列車の帆、テント、ユニフォームなど)。戦後土地は主に食糧の栽培に使われるようになり、亜麻は不足しました。亜麻不足により繊維は非常に高価になりました。ベルギーのリネン織物業者は「ベルギーリネン織物業者連合会」を結成し手に入る亜麻を互いに分配しどの織物職人も同じ機会を得ることができるようになりました。この間アンドレ・デクエは幹事に任命され40年間その地位を維持することになります。

アイリッシュリネンの歴史は、少なくとも17世紀、リネンの主原料となる亜麻がアイルランドで栽培され始めたことに始まります。当時、アイルランドは大英帝国の一部であり、リネン産業は英国政府によって厳しく規制・管理されていました。

18世紀、アイルランドのリネン産業の発展に大きな役割を果たしたのが、ユグノー派の織物職人ルイ・クロンメリンです。クロンメリンはフランスでリネン産業に携わっていました。しかし宗教的迫害から逃れるため1698年にアイルランドに逃亡してきました。アイルランドでは、北部、特にリスバーン周辺でのリネン産業の確立に貢献しました。彼は新しい織物技術や機械を導入し地元の労働者に高品質のリネン生地を織る技術を教えました。このような多難にもかかわらず亜麻の加工やリネンを織るための新しい技術や機械の開発などにより18世紀から19世紀にかけてアイルランドのリネン産業は非常に大きく成長拡大していきました。アイリッシュリネンはその優れた品質と耐久性で知られるようになり、ヨーロッパをはじめ世界中に輸出されるようになります。この間多くのアイリッシュリネン生産者が複雑な柄やデザインを織る技術を習得しアイリッシュリネンはその複雑な織り、光沢、柔らかい肌触りで知られるようになっていきます。

20世紀に入ると、アイルランドのリネン産業は困難に直面します。特に2つの世界大戦と世界恐慌の影響で高級生地への需要が大きく減少しました。しかし多くのアイリッシュリネン生産者が技術革新を続け、温暖な気候に適した軽量で薄手のリネンなど、新しいタイプのリネン生地を開発し続けました。現在でもアイリッシュリネンは品質とクラフトマンシップの象徴として世界中のテキスタイル専門家や愛好家から高い評価を受けています。多くのアイリッシュリネン生産者が伝統的な技術と高品質の素材を用いて世界最高級のリネン生地を生産しており、この産業はアイルランドの文化・経済遺産として重要な役割を担っています。

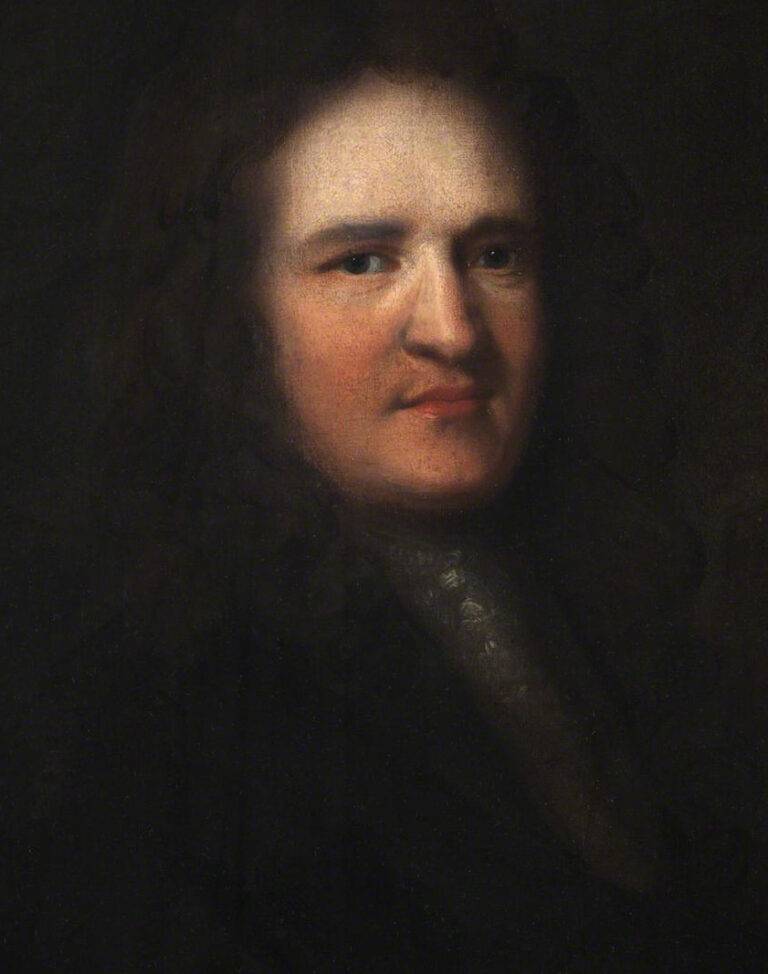

Crommelin was born in May 1652 at Armandcourt, near Saint-Quentin in Picardy, into a family of landowners with a tradition of growing flax; his father, Louis Crommelin, married in 1648 to Marie Mettayer, was wealthy and had four sons, Samuel-Louis, Samuel, William, and Alexander. Samuel-Louis Crommelin, called Louis, was in business flax-spinning and linen-weaving. The family was Protestant, and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 hit hard even though Louis was a Catholic convert of 1683. With his son and two daughters he made his way to Amsterdam. There he became partner in a bank, and was joined by his brothers Samuel and William.

クロンメランは1652年5月、ピカルディーのサン・カンタンに近いアルマンドコートで、亜麻栽培の伝統を持つ地主の家に生まれました。父のルイ・クロンメランは1648年にマリー・メッタイヤーと結婚し、裕福でサミュエル=ルイ、サミュエル、ウィリアム、アレクサンダーの4人の息子を持ちます。ルイと呼ばれるサミュエル=ルイ・クロンメリンは亜麻紡績とリネン織りを業としていました。ルイは1683年にカトリックに改宗したが、一家はプロテスタントであり、1685年のナントの勅令の廃止は大きな痛手となりました。息子と二人の娘を連れてルイはアムステルダムに向かった。そこで銀行の共同経営者となり兄弟のサミュエルとウィリアムと合流した。ウィリアム3世とメアリー2世のもと、トーマス・サウスウェルはアイルランドの産業を発展させるための資金を得ることができました。当時ユグノー教徒のリネン労働者はすでにリネンの製造が行われていたリスバーンに移住するよう奨励されていました。1696年、イギリス議会は、アイルランドからイギリスへの麻と亜麻の全製品を無税で受け入れる法律を可決し、アイルランド議会は1697年11月にリネン製造の育成に関する法律を可決します。ウィリアム3世は、アイルランドの毛織物貿易を奨励する一方でリネン製造業の育成を図る政策をとりました。 クロンメリンはサウスウェルが引き入れた最も著名なユグノーでした。 彼は1698年の秋にリスバーンに到着し1699年4月16日の追悼文でリネン産業の改善について提言しすぐに実行されることになりました。クロメリンは「アイルランド王立リネン製造監督官」に任命されこの計画に資金を確保しました。1702年アン女王はその勅許を確認。クロンメリンはまずフランドルやオランダから織機を取り寄せユグノー族の織工を導入しました。初期に彼はアイルランドの紡ぎ車を採用しますがその改良に努めます。縦糸を制御する筬の製作者は、カンブライのアンリ・マルク・デュ・プレ(1750年没)でした。コンウェイ男爵は織物工房の敷地を提供しアイルランド人の徒弟が採用されました。オランダ人は農民に亜麻の栽培を教え漂白作業の監督をするよう命じられました。クロンメリンがアルスター地方で織物技術教育のシステムを作り上げたとされるのにはそれなりの理由があったということです。クロンメリンは兄弟に助けられ、リネンやキャンブリックが輸入繊維に取って代わることができました。1705年、William Crommelinの経営により、キルケニーに工場が開設されます。Crommelinは事業を拡大し、Rathkealeや他の場所でも麻の帆布を製造するようになりました。1716年に年金が支給され、1727年7月14日にリスバーンで75歳で死去。彼は他のユグノーと共にリスバーン大聖堂の墓地の東の隅に埋葬されました。