The Kashmir shawl, known for its unique Kashmiri weave and fine shahtoosh or pashmina wool material, preceded the contemporary cashmere shawl. Today, variations of the shawl include the pashmina and shahtoosh shawls, often referred to simply as pashmina and shahtoosh. While originally designed as a covering for men in India, it has since become a symbol of nobility and rank in popular cultures across India, Europe, and the United States. It is often given as an heirloom on a girl’s coming-of-age or marriage and used as an artistic element in interior design.

Map of Punjab, Sind, Rajputana and Kashmir, 1902.

Cashmere Shawls: Weaving, 1863

William Crimea Simpson

Spinning and weaving woolen shawls, Srinagar, Kashmir, India c.1901

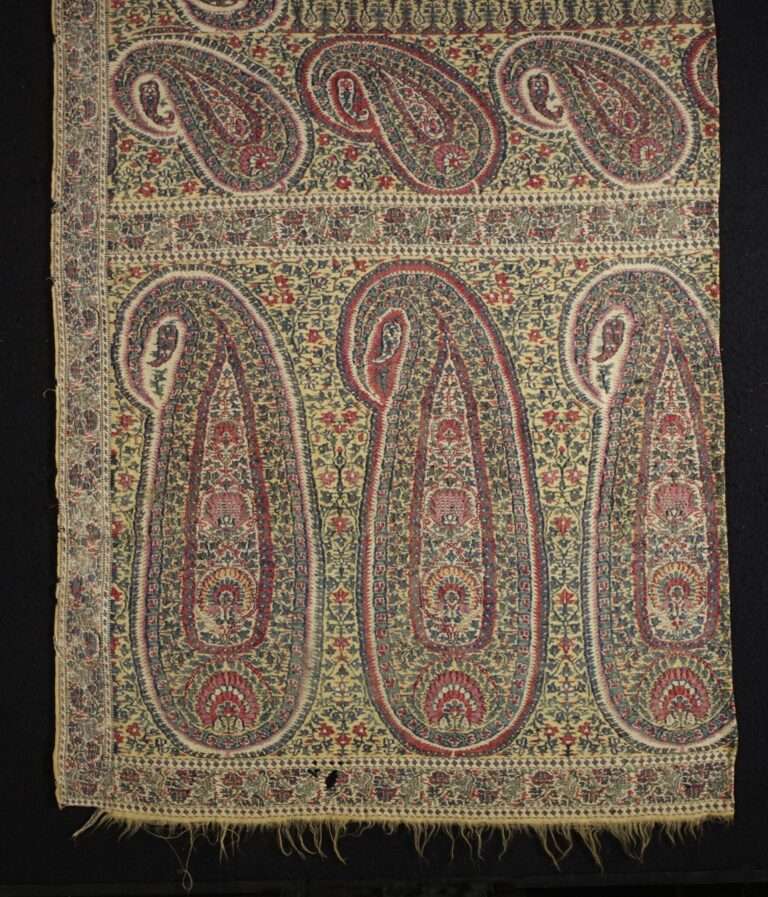

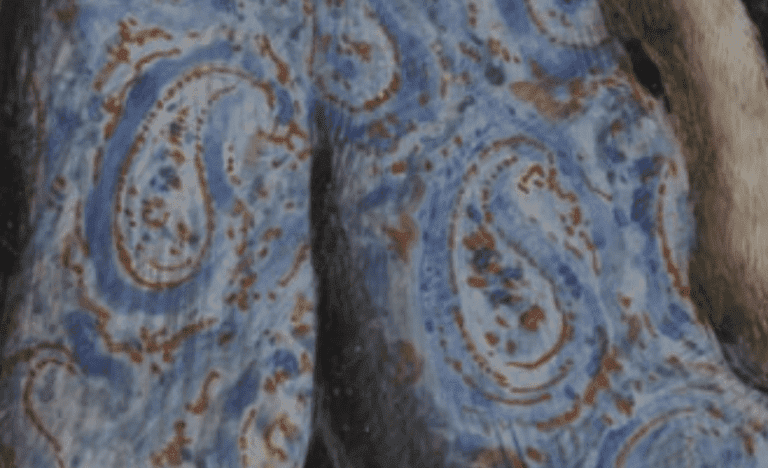

The Kashmir shawl’s warmth, light weight, and characteristic buta design led to the creation of the global cashmere industry. It has been used in high-grade sartorial fashion since the 13th century and was even used by Mughal and Iranian emperors in the 16th century. When it arrived in Britain in the late 18th century, its use by Queen Victoria and Empress Joséphine popularized it as a symbol of exotic luxury and status. Today, the Kashmir shawl has become synonymous with the Kashmir region, inspiring mass-produced imitation industries in India and Europe and popularizing the buta motif, now known as the Paisley motif after factories in Paisley, Scotland that replicated it.

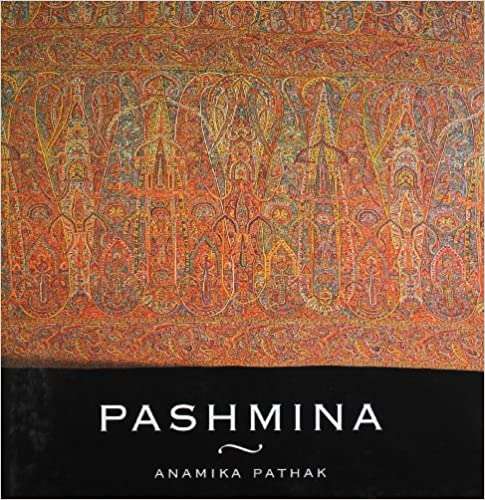

The Kashmir shawl is renowned for its unique weaving technique and fine wool material. However, its definition has varied over time and across different regions, based on factors like the material used, construction method, intended use, and wearer’s status. Shahtoosh shawls are no longer produced due to the ban on products made from the Tibetan antelope. In India, men wore the shawl, with its fineness indicating nobility or royal favor, while in the West, it represented different commodities, worn first by men, then by women, and eventually used for interior design. The definition has been muddled by fake and imitated shawls, and some people use cashmere and pashmina interchangeably, assuming they are the same. However, pashmina is a finer type of cashmere, and not all cashmere is pashmina. In the late 19th century, weavers in Punjab created imitation shawls using Merino wool and the Kashmiri technique, called raffal. Recently, sellers in the West adopted the term “pashmina” to sell generic cashmere shawls, moving its association from high fashion to middle-class popularity in the 2000s.

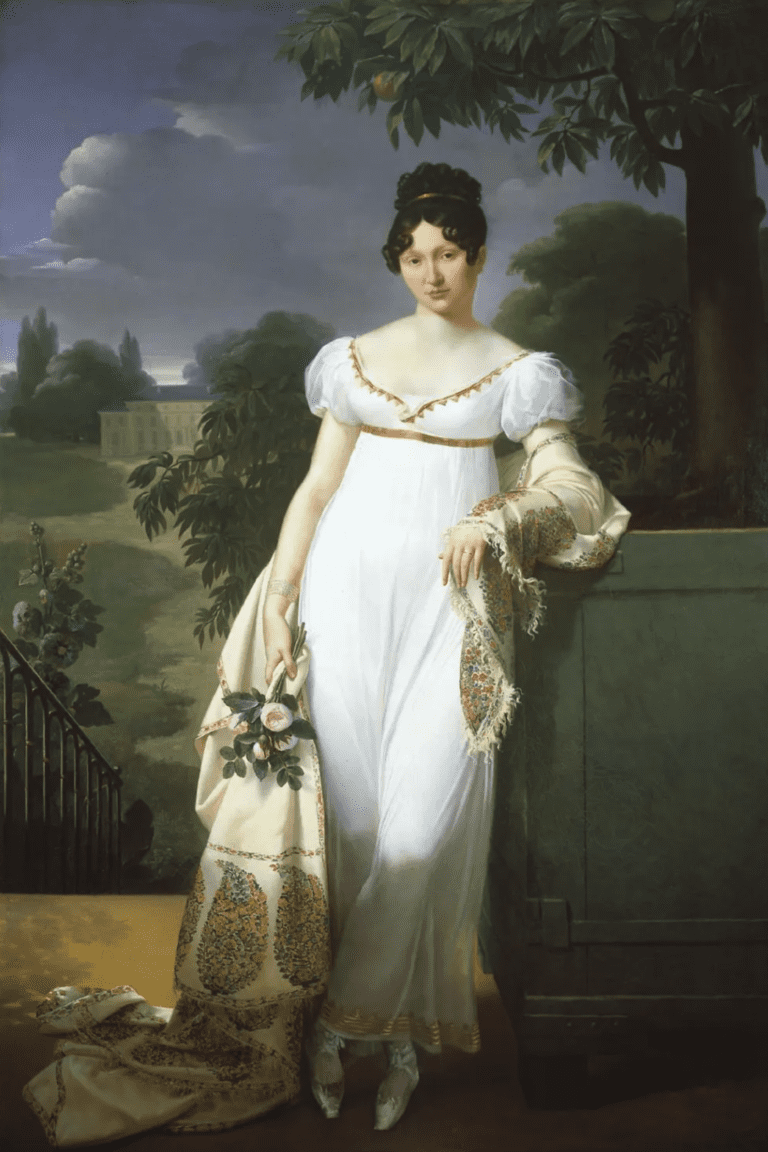

Kashmir shawl with Joséphine Bonaparte

The shawl, typically a square or triangular piece of fabric, is draped over women’s shoulders for added warmth. Although shawls were traditionally worn by both genders in Asia and the Far East, they made their way to Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with the rise of British influence in the region. This led to a rivalry between Persia and the Kashmir region in producing intricately woven or embroidered fabrics.

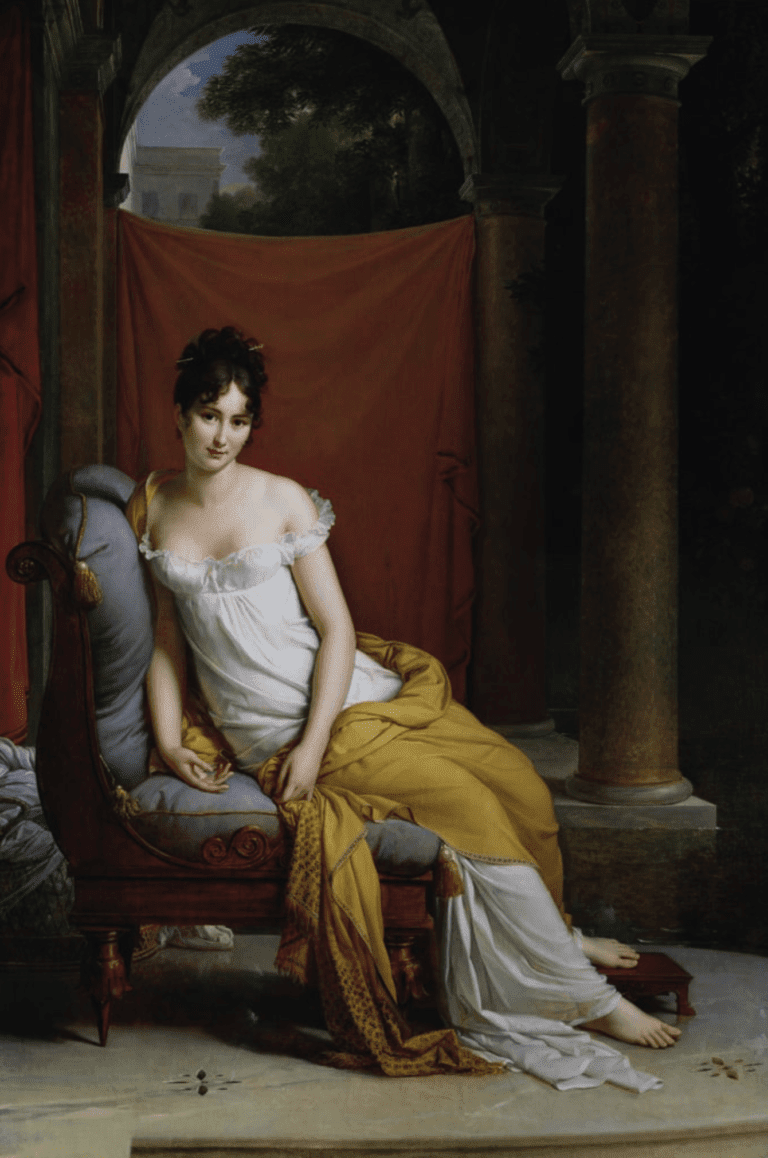

The shawl was a highly sought-after accessory during the Directory, Consulate, and imperial periods, made from the finest and most expensive materials, especially cashmere. It was a must-have item in the wardrobe of any fashionable woman of the time. Josephine, the future empress of France, was a well-known fashion enthusiast who owned many shawls, including one of the exotic shawls brought back from Egypt by Bonaparte. Initially, she had reservations about the shawls but soon changed her mind and even amassed an enormous collection of them.

(she remarked in a letter to her son, Eugène, “I have received the shawls They seem most ugly to me.)

Portrait of Joséphine later in life by Andrea Appiani

Josephine Tasher de la Pagerie (1763-1814) Empress of the French, gazing at a bust of her son Eugene de Beauharnais (1781-1824) at Malmaison, 1808

The shawl was a highly sought-after accessory during the Directory, Consulate, and imperial periods, made from the finest and most expensive materials, especially cashmere. It was a must-have item in the wardrobe of any fashionable woman of the time. Josephine, the future empress of France, was a well-known fashion enthusiast who owned many shawls, including one of the exotic shawls brought back from Egypt by Bonaparte. Initially, she had reservations about the shawls but soon changed her mind and even amassed an enormous collection of them.

Her initial reservations soon disappeared, and she became an avid collector of shawls. An account from the time described,

Originally, cashmere wool sourced from the Himalayas was imported from distant oriental countries like India. However, due to the continental blockade which aimed to restrict the export of British products to Europe, cashmere was prohibited and added to the banned items list. To overcome this setback, a French mill owner named Guillaume Ternaux created French cashmere, an innovation that earned him recognition through induction into the Légion d’honneur. Nonetheless, it took France some time to perfect the product to achieve the same level of weave quality and delicacy as the imported foreign fabrics.

The shawl, with its elongated shape, offered versatility in terms of how it could be worn. It could drape over the shoulders, be tied around the front, or even be wrapped around the head like a turban. As an additional layer of warmth, it could serve as a substitute for a jacket while also adding a stylish touch to an outfit. The cashmere shawl held a significant place in Parisian high society and bourgeois circles, often passed down through generations from mothers to daughters.However, during the later years of the empire, the shawl began to lose its popularity. It was gradually replaced by more practical and warmer clothing, such as the hooded witchoura – a fur-lined coat similar to the Polish wilczura.

The Kashmir shawl has a traditional construction using either shahtoosh or pashmina wool. Shahtoosh is sourced from the delicate hairs on the Tibetan antelope’s underbelly. The term cashmere is often used interchangeably with pashmina, which is incorrect. Both cashmere and pashmina are produced from the fibers of the Changthangi goat, but pashmina is a superior type of cashmere with fibers ranging from 12 to 16 microns in diameter, while generic cashmere fibers range from 12 to 21 microns in diameter.

The world’s finest hair averaging 7-10 microns in diameter is used to make Shahtoosh shawls, which come from the hair of the Tibetan antelope. These shawls are made only from wild animals, grown during harsh winters and collected in the summer after rubbing off on rocks and shrubs, for weaving. In India, the fineness of a shawl was traditionally seen as a mark of nobility, which is why they were initially reserved for members of the Mughal aristocracy. In the mid-eighteenth century, these shawls became popular after being used by Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Empress Joséphine of France. The shawls became known as “ring shawls” during Mughal times for their lightness and fine quality, which allowed a one-metre by two-metre shawl to be pulled through a finger ring. They remain known as such today and serve as a status symbol, valued on average between USD $2,000 and $3,000, but for up to $15,000. However, the export of shahtoosh shawls is now prohibited under CITES and their production and sale banned under wildlife protection laws in India, China, and Nepal. Domestic laws in the US also prohibit their sale.

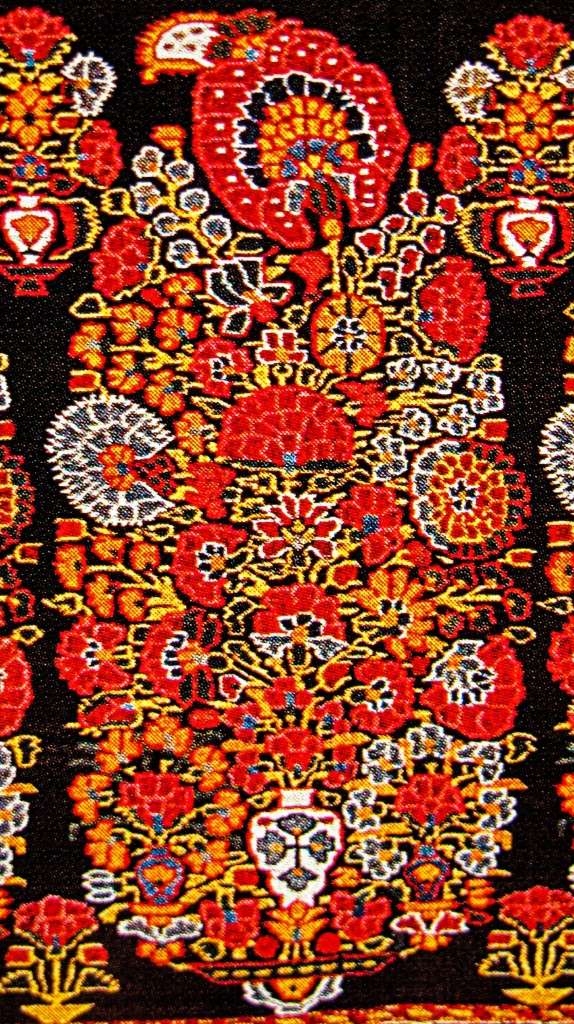

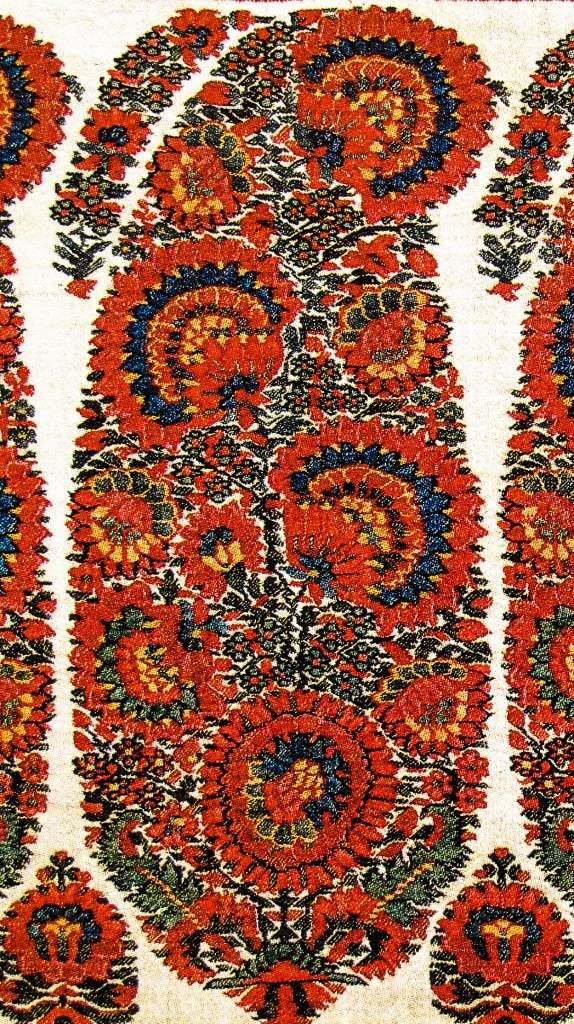

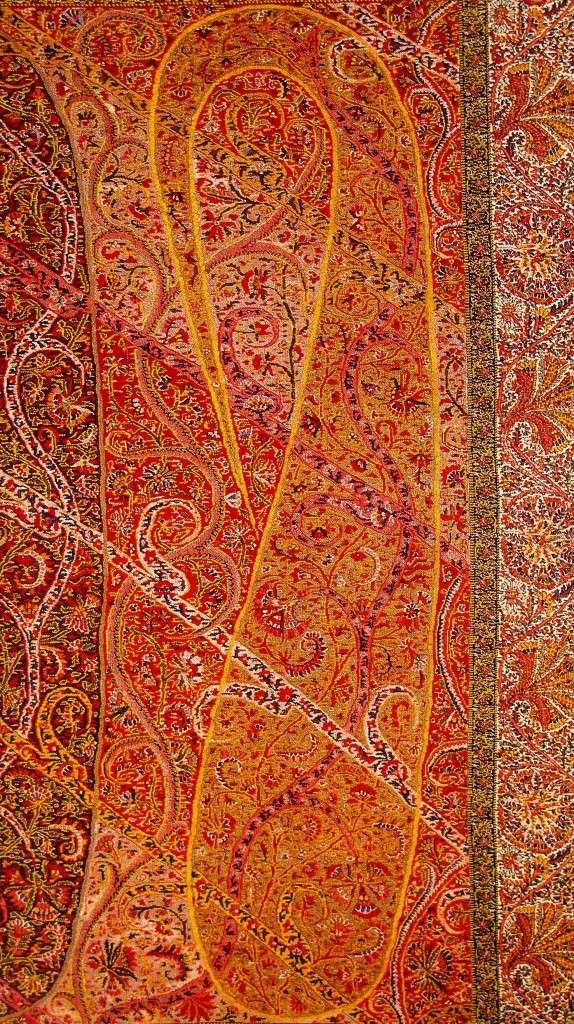

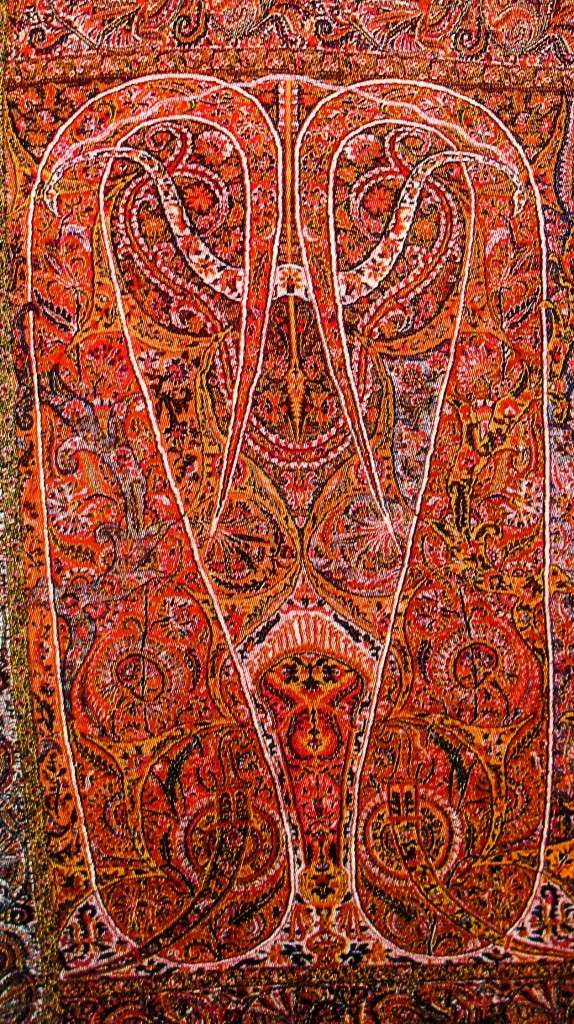

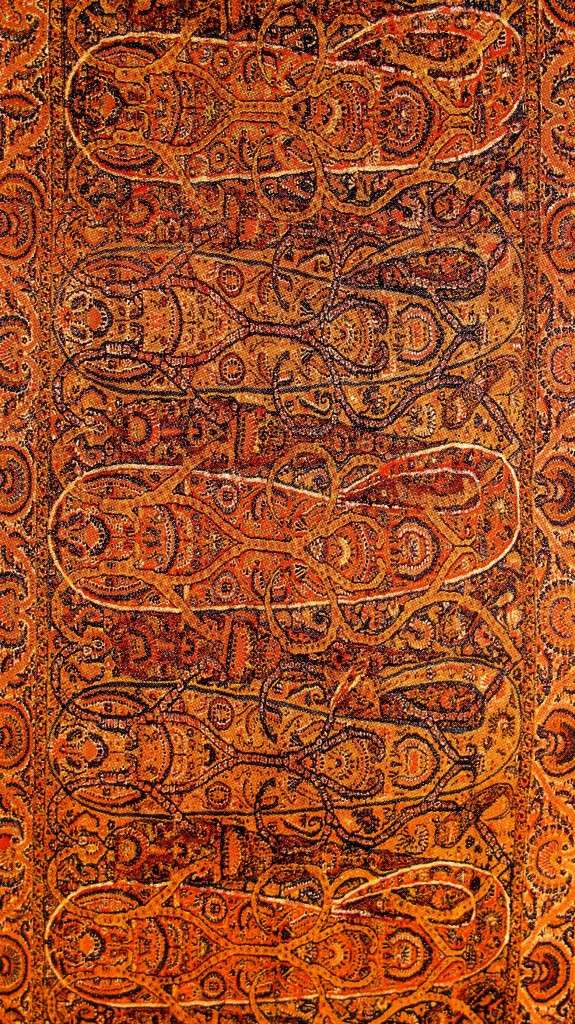

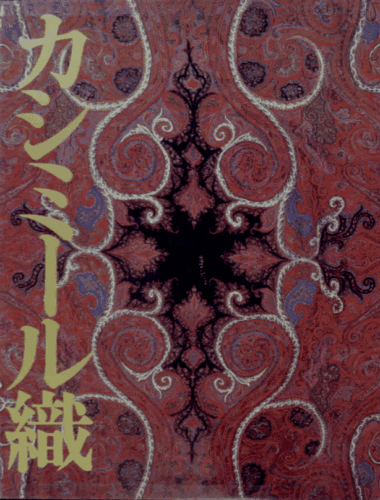

The Kani shawl is the traditional style of Kashmir shawl, originally produced in the village of Kanihama. It is known for using a variation of the “twill tapestry technique”, which is similar to European tapestry weaving techniques but differs in the horizontal loom and operation closer to brocading. In this technique, the weaver passes a weft over-and-under two warps, using discontinuous wefts to vary the color and create distinct color areas on both sides of the fabric. This allowed for the creation of intricate patterns, such as the buta design, to be woven onto the shawls.

The Empire style of fashion, also known as the Regency style, was a fashion trend that emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries during the time of the French Empire under Napoleon Bonaparte. The style was characterized by high-waisted dresses with long, flowing skirts, often made of lightweight fabrics like muslin or silk, and featuring delicate, intricate details such as embroidery, lace, and tassels.

The dresses were typically sleeveless or had short sleeves, and were often worn with a shawl or a wrap to cover the shoulders and arms. The style emphasized a natural waistline and a graceful, feminine silhouette, with a focus on simplicity and elegance. The Empire style was also notable for its use of classic motifs from ancient Greece and Rome, such as columns, laurel wreaths, and draped fabrics.

The Empire style of fashion was popularized by the French Empress Josephine, who was known for her elegant and sophisticated sense of style. The style was also influenced by the neoclassical art and architecture of the time, which emphasized simplicity, symmetry, and classical forms. Today, the Empire style remains a classic and timeless fashion trend that is still admired and emulated by many.

Madame Charles Maurice de Talleyrand Périgord 1761-1835,

Francois Pascal Simon Gerard 1804

Portrait of Joséphina Fridrix

Henri-François Riesener 1813

Regency style—white dress circa 1808. ©wikimedia commons

Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis wears a dress with a sheer top layer over a partial lining and a patterned shawl. She wears a gold armlet on her left arm. Her hair is styled in loose waves at the temples and over her ears. Massachusetts, 1809. ©wikimedia commons

Portrait of Madame Recamier (1777-1849) Baron François Pascal Simon Gérard

Portrait of Angelica Kauffmann, half length in white wearing a red shawl Joshua Reynolds

Actuary The Empire style of fashion was popular from approximately 1804 to 1815, during the time of the French Empire under Napoleon Bonaparte. The style was named after the empire and was also known as the Regency style, as it coincided with the Regency period in England.

The Empire style of fashion was popular for several reasons. Firstly, it reflected the social and political changes of the time. Napoleon’s empire was characterized by a sense of grandeur and opulence, which was reflected in the elegant and luxurious fabrics used in the clothing of the era. At the same time, the simplicity and classical forms of the Empire style also reflected the neoclassical art and architecture of the time, which was admired for its elegance, symmetry, and refined taste.

Secondly, the Empire style was also popular because it emphasized a more natural and feminine silhouette, which was a departure from the more rigid and constricting styles of the previous era. The high-waisted dresses of the Empire style accentuated the natural waistline and created a graceful and flowing silhouette, which was both comfortable and flattering.

Finally, the Empire style was popular because it was associated with the romantic and exotic world of the East, which was a major source of inspiration for fashion designers of the time. The use of delicate fabrics like muslin and silk, combined with intricate details like embroidery and tassels, created a sense of lightness and airiness that was evocative of the romantic and exotic world of the Orient.

During the period when the Kashmir shawl gained popularity in Britain, women from the northeastern coast of the United States also adopted the trend of wearing them. This fashion trend in the United States followed the lead of western European fashion. In the 1860s, shawls were a popular holiday gift and Indian shawls were considered a wise purchase in 1870. However, by the late 1870s, fake shawls started to overshadow genuine Indian shawls in advertisements. From the 1880s until World War I, affluent European and American women began using Kashmir shawls as decorative items on pianos rather than wearing them.

The term “Russian Regency style” typically refers to the period of Russian history from 1810 to 1830, during the reign of Tsar Alexander I. This period saw the emergence of a unique Russian interpretation of the Empire style, which was also known as the Russian Classicism or Russian Empire style.The Russian Regency style was heavily influenced by the Empire style that was popular in France and other European countries at the time. However, it also drew on traditional Russian motifs and architectural styles, such as the onion dome and the use of colorful mosaics and decorative tiles.

One of the most significant architects and designers of the Russian Regency style was Andrei Voronikhin, who designed several notable buildings during this period, including the Kazan Cathedral in St. Petersburg. Voronikhin’s designs were characterized by their grandeur, symmetry, and use of classical motifs. In addition to architecture, the Russian Regency style also influenced fashion and decorative arts, with designers and craftsmen creating luxurious and ornate items such as porcelain, furniture, and jewelry. The style was also associated with a renewed interest in Russian folklore and traditional crafts, which were incorporated into the decorative arts of the time.The Russian Regency style was significant not only for its artistic and cultural achievements but also for its political and social context. The reign of Tsar Alexander I saw significant political reforms and the emergence of a more liberal and progressive society, which was reflected in the arts and culture of the time.

The Regency style, also known as the Empire style, was a fashion and design trend that emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, during the Regency period in England. The Regency period lasted from 1811 to 1820, when King George III was declared unfit to rule and his son, the future King George IV, became the Prince Regent and ruled in his place.

The Regency style was characterized by a departure from the more formal and rigid fashions of the previous era, and an embrace of more natural, flowing, and romantic designs. Women’s fashion, in particular, underwent significant changes during the Regency period. The high-waisted dresses of the Empire style became popular, featuring long, flowing skirts, and often made of lightweight fabrics like muslin or silk. The Regency style was heavily influenced by the neoclassical art and architecture of the time, which emphasized simplicity, symmetry, and classical forms. This influence was reflected in the clothing of the era, which often featured classical motifs such as columns, laurel wreaths, and draped fabrics.

The Regency style was also influenced by the romantic and exotic world of the Orient, which was a major source of inspiration for fashion designers of the time. The use of delicate fabrics like muslin and silk, combined with intricate details like embroidery and tassels, created a sense of lightness and airiness that was evocative of the romantic and exotic world of the East.The Regency style was popularized by figures such as Beau Brummell, a famous dandy and fashion icon of the time, as well as by Jane Austen, whose novels and characters are often associated with the Regency era. Today, the Regency style remains a classic and timeless fashion trend that is still admired and emulated by many.

The UK and Regency style will be presented in a separate item

What is the “paisley” meaning

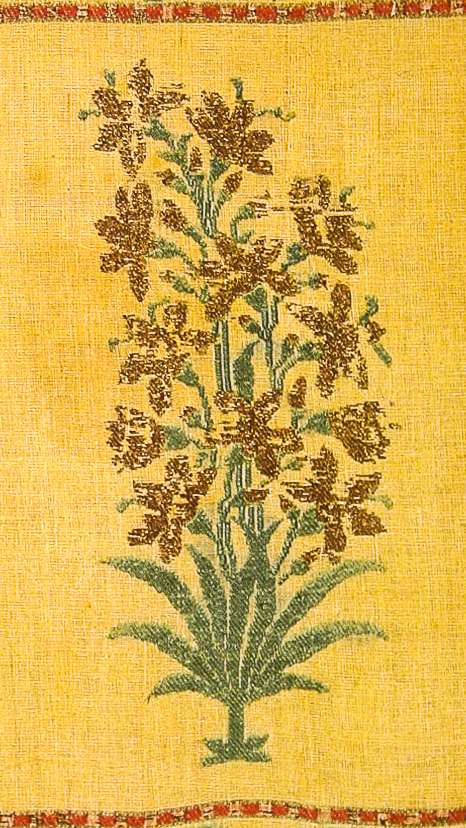

The paisley pattern originated in Persia, which is in the Middle East, and it became popular in the West during the 18th and 19th centuries. It was imported from India, especially in the form of Kashmir shawls, and was then replicated locally. The town of Paisley, in Scotland, became a hub for the production of paisley designs, hence the name “paisley”.

the Industrial Revolution played a significant role in the production and spread of paisley designs. The development of new technologies during the Industrial Revolution allowed for more efficient production of textiles, and paisley designs were mass-produced using these methods. The town of Paisley in Scotland, which gave the design its name, was an important center of textile production during this time. The increased availability of textiles and the popularity of the paisley pattern helped to make it a widespread and enduring design in Western fashion and decorative arts.

In Europe, the design went through another transformation as the hollow of the boteh came to be filled in with intricately stylised floral compositions. The earliest iterations of manufactured Kashmiri shawls came from Edinburgh, Scotland which was soon eclipsed by another Scottish town, Paisley, hence giving it its popular name. It was also the first town to successfully adopt the Jacquard loom in production, which allowed an intricate pattern while easing the weaver’s task.

The Paisley shawl industry was highly regarded during its peak, and even after its decline in the late 19th century, it has maintained a distinct identity and status in Scotland and beyond. While some may exaggerate its uniqueness, similar woven shawls were produced in Edinburgh and Norwich in the early 19th century, as well as in various locations in France. Today, it can be challenging to distinguish one type of shawl from another, as they often share similarities in quality and design. However, the Paisley name is synonymous with the distinct teardrop pattern that appears in countless variations on these shawls. This pattern, with its origins in early Persia and India, along with the town’s distinctive features and the original craftsmen, have given rise to a myth and romance surrounding the Paisley shawl that continues to endure.

The British and French shawl industries emerged in the 18th century, seeking to replicate the high-quality, handmade Kashmir shawls imported from India. These Indian shawls, crafted from cashmere wool and sometimes antique, were expensive gifts for women, often given to celebrate engagements or weddings, and came to symbolize luxury, taste, and old wealth in 19th-century literature. The Paisley shawl industry aimed to recreate this image and product’s high quality, even going so far as to import cashmere goats to produce the wool. However, this experiment failed, as the quality of the wool changed in a different climate. Despite Paisley shawls’ value never matching those from Kashmir, the best-designed and made shawls still commanded a high price.

In the beginning, the Paisley shawl’s imitation of the Kashmiri originals was often a subject of ridicule rather than admiration. Walter Scott’s novels contain several passages that highlight the shawl’s lack of cultural authenticity. For instance, in this excerpt from the Chronicles of the Canongate:

“While the dear souls were thus smothering me with rose-leaves, the merciless old lady carried them all off by a disquisition upon shawls, which she had the impudence to say, arose entirely out of my story….she threw all other topics out of the field, and from the genuine Indian, she made a digression to the imitation shawls now made at Paisley, out of real Thibet wool, not to be known from the actual Country shawl, except by some inimitable cross-stitch in the border. “It is well”, said the old lady, wrapping herself up in a rich Kashmire, “that there is some way of knowing a thing that costs fifty guineas from an article that is sold for five: but I venture to say there are not one out of ten thousand that would understand the difference.”

The Paisley shawl’s rise in status was due in part to the weavers’ dedication to producing high-quality designs and adopting new weaving technologies, leading the best weavers to see themselves as artists. The industry’s iconic reputation was also bolstered by a longstanding tradition of cultural vibrancy among the community of Paisley shawl weavers, who were not only designers but also poets and botanists, as botanical art was often linked to textile design. As the town’s primary manufacturing industry and a unique textile craft in Scotland, high-quality Paisley shawl weaving was considered a male skill, with women in the family involved in stitching the hems and fringes as part of a household or small workshop production system.

The production of Paisley shawls was a part of the fashion industry, leading to fluctuations in demand. In 1842, during a trade downturn, Queen Victoria purchased seventeen Paisley shawls and frequently wore them on notable occasions, including the christening of the Prince of Wales in the same year. The queen’s visits to Scotland and her display of Paisley shawls, even in her old age, provided periodic boosts to the industry, such as during the “golden jubilee” in 1888. Members of the royal family regularly received gifts of Paisley shawls, which were often mentioned in the press. The Princess of Wales received one for her wedding in 1863, and the tradition continued into the twentieth century with antique shawls presented for the royal wedding of 1922 and to the Queen during her visit to Paisley in 1938. Notable Scottish aristocrats also publicly demonstrated their cultural attachment to Paisley shawls. In 1933, at a Holyrood garden party in Edinburgh, Lady Aberdeen wore her ‘heirloom Paisley shawl of duck-egg green,’ emphasizing her championing of Scottish and Irish textile craftwork during her public life as the wife of a senior politician.

Exhibitions played an important role in showcasing Paisley shawls, both during the height of the industry and after its decline. The Great Exhibition of 1851 and subsequent international and local exhibitions regularly featured Paisley-made shawls. Historical exhibitions began shortly after the industry’s demise, with the first major display taking place in June 1905 at the Free Public Library and Museum in Paisley. This exhibition featured 650 specimens of shawls from Paisley, Oriental, French, and other regions. The museum, which opened in 1870, was established by Sir Peter Coats of the Paisley thread-manufacturing firm and was based on the collections of the Paisley Philosophical Society. The town council’s first purchase for the museum was a set of the Forbes Watson collection of Textile Manufactures of India, which cost £150. Other shawls and exhibits were donated over time.

The 1905 exhibition aimed to educate the youth and visitors attending the Co-Operative Congress about Paisley’s greatness and to expand the museum’s collection by attracting more shawl specimens. The Co-Operative Congress was a significant international event with widespread media coverage, attended by hundreds of delegates. The exhibition, which lasted three weeks, attracted 16,000 visitors and was organized by local historian Matthew Blair, a former weaver who also wrote about the Paisley thread industry. The exhibition featured contributions from the last company to weave a reversible shawl in 1903, Messrs Walters, Cook & Co. Subsequent exhibitions were held in Scotland, such as the one in May 1915 in the club rooms of the Glasgow Society of Lady Artists, which mainly showcased loans from John Clark of the Paisley thread-making company. The Scotsman reported the event with a sense of nostalgia, acknowledging the decline of the Paisley shawl industry and its transition into a historic artifact, preserved as a family heirloom.

In June 1923, the Stirling Smith Institution hosted an exhibition of 119 shawls, showcasing the past and different phases of the “beautiful art.” The exhibit was curated by Edward Cook from Walters, Cook & Co., and included the last shawl to be woven in Paisley. At the opening ceremony, the Town Clerk, acting as Secretary to the Trustees for the Smith Institution, spoke about the artistry, craftsmanship, and poetry of the weavers, as well as the shawls’ role as a universal bridal present in Scotland for 75 years. The exhibition demonstrated a nexus of ideas related to Scottishness, including gift-giving, celebration, passing worlds and ideals, and beauty. The Saltire Society, founded in 1936 to celebrate Scottish culture, held a Paisley shawl exhibition in May 1947 in Edinburgh’s Lawnmarket, based on the private collection of Miss Dorothy A. Whyte, who was wartime curator of the Paisley Museum.

“These shawls which had incorporated the high art and skill of the Orient, came into being in this country, reached their heyday and waned within the short space of some sixty years. From being the proud possession of every bride, they had passed to period pieces prized by museums and a few private owners”

Paisley, Scotland had a history as a center for textile manufacturing even before the rise of the Kashmir craze. However, the town’s focus had been on producing silk goods, which had gone out of fashion. In the early 1800s, a local named Thomas Coats recognized the opportunity presented by the growing interest in Kashmir shawls and worked to transform Paisley into a center for thread and weaving. While the shawls produced in Paisley were not of the same caliber as those from Kashmir, the infrastructure was already in place, allowing Paisley to quickly become the leading textile center in the world for a period of time.

The Clark Brothers established their mills next to the Hammils, a waterfall created by a band of hard volcanic rock across the river bed. Two mills, one on each side of the river, were powered by the force of water flowing over the falls. The brothers had realized in 1812 that selling cotton thread for domestic sewing could be a profitable business, and thus laid the foundation for much of Paisley’s fame and prosperity in the late nineteenth century. The small thread production business at Seedhill grew steadily throughout the century and received a major boost with the refinement of the sewing machine in the mid-century. The increasing use of sewing machines in clothing factories and households led to a huge demand for cotton thread, which was the only type smooth enough to run through the mechanism. By the end of the century, the Clarks had constructed a vast complex of spinning and twisting mills extending hundreds of yards from the original site near the Hammils.

James Coats earned his fortune in the early 1800s by producing crepe shawls and running his wife’s tambouring business colled “Coats Mills”. In 1826, he followed the Clark brothers’ example and established a small thread twisting factory behind his home at Ferguslie. Four years later, James retired and passed the business to his sons James and Peter, forming J. & P. Coats. After James’ early death, his younger brother Thomas took his place. Together, Peter and Thomas expanded the business into one of the largest industrial concerns in 19th-century Scotland. In 1896, they acquired the Clarks’ firm, making Coats even more prominent. Today, Coats remains one of the largest multinational companies, but their operations in Paisley have significantly decreased.

Victoria’s reign, remains a relatively unknown figure due to the textile industry’s practice of keeping designers’ names secret. He was born in 1825 and passed away in 1871. Fortunately, we are able to admire his designs today thanks to his son, also named George Charles Haite, who donated 60 of his father’s designs to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1911. Haite’s “Cashmere” patterns were inspired by woven shawls produced in the Indian province of Kashmir, featuring a slender flower as the basic unit of design. This Persian motif merged with another Indo-Persian motif, the vase of flowers, which ultimately became the ubiquitous Paisley ‘pine cone’ shape in British shawl designs. One of Haite’s designs exemplifies this shape, while another showcases a stylized vase intertwined with abstract plant forms.

During the 1770s, the Indian shawl became a popular fashion item among English dress. By the 1820s, British manufacturers began to emulate the original shawls. Over time, the designs became more intricate and diverse, deviating from their Indian roots. Towards the end of his life, Haite acknowledged that fashion trends and intermediaries had enslaved designers, making it a profession he wouldn’t want his son to pursue. Haite’s true passion lay in his Cashmere designs. Creating trendy designs felt like a degradation of his art, a sentiment he expressed more than once. Unfortunately, Haite passed away in 1871 from smallpox, a time when the popularity of Kashmir shawls was waning. Below are some more of his designs.

Design for a Paisley shawl

Textile Design

ca. 1850 ©V&A

George Haite shawl design, 1853, for J. Dickson

Fabric Designs for Paisley Shawls by George Haite ©V&A

When he was a young man, the fashion for paisley-style shawls was at a height. Fashionable women counted their wealth in jewellery, lace and shawls. Shawl printing began to bring these luxury items within reach of more people. George Haite showed talent for designing printed shawls and was to become Swaisland’s foremost shawl designer in the mid-1800s. Haite would have seen the French shawl designs purchased by Swaisland from Paris designers like G. Meynier and Edouard Hartweck, and was undoubtedly encouraged to follow Parisian fashion. But Haite brought an English sensibility to the field, incorporating textures suited to printing, rather than following traditional strictures based on weave designs.

It is possible that J. Dickson, who might have been John Dickson and Co., a Cheapside warehouseman active from the 1830s until 1857, was one of Haite’s clients. Dickson had requested a change to the shawl end that Haite had presented with an overlay, and the leafy figures were crossed out in pencil, indicating that only the more detailed figures would be used in the final pattern. While designers were expected to provide clients with options, it is unfortunate that conservative elements were frequently preferred over more innovative design elements, from a modern perspective.

Captain John Foote by Joshua Reynolds 1760

Mrs. Horton, Later Viscountess Maynard died 1814-15. Sir Joshua Reynolds about 1770s

Portrait of Anne-Marie-Louise Thélusson, Countess of Sorcy

1790

Marie-Laetitia Ramolino (1750-1836) 1803 Baron François Pascal Simon Gérard

Marie-Laetitia Ramolino (1750-1836) Baron François Pascal Simon Gérard 1803

Portrait par Robert Lefèvre (c. 1800-1805), Saint-Pétersbourg, musée de l’Ermitage.

Roustam Raza Horace Vernet

1810

Portrait of the Countess of Tournon Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres 1812 ©philamuseum

Amalie Auguste of Bavaria

Karl Joseph Stieler 1823

Portrait of a young lady in a red dress with a Kashmir Paisley Shawl – Eduard Friedrich Leybold – 1824

Adele de Guerneval d’Esquebecq, Marquise de Bethisy Carl von Steuben 1835

Daniel Saint’s Lady with a Greyhound, 1839-42

The Story of Balaclava: ‘Wherein he Spoke of the Most Disastrous Chances’ Rebecca Solomon 1855

Le baiser (The kiss) Jules Trayer 1858

Will you go out with me, Fido Alfred Emile Stevens 1859

Dolphus Meag & Cie (DMC), 1866, no. 20: Loeb, Caroline and F. Appel, 1866. ©wikipediacommon

The Visit Alfred Emile Stevens 1869

After the Ball Alfred Emile Stevens 1874

Cashmere John Singer Sargent 1908

Two White Dresses, John Singer Sargent 1911

Nonchaloir John Singer Sargent 1911

Where did the paisley pattern come from?

There are several theories of origin for what is now known as the paisley pattern. It is almost certain to have originated in the Persian region, but there are some differences between scholars in the motifs used. My guess is that they are probably all correct.

The “paisley pattern” is a design motif that originated in India and was introduced to Europe through trade with the East India Company in the 17th century. The pattern features a curved teardrop shape with intricate details and is often used in textiles and decorative arts. The name “paisley” refers to the town of Paisley, Scotland, which became a center for textile production in the 19th century and was known for its production of shawls featuring the paisley pattern. Regardless of the exact origins of the name, the paisley pattern became popular in Europe and America in the 19th century and remains a popular design motif today. It has been used in a wide range of applications, including clothing, accessories, and home decor.

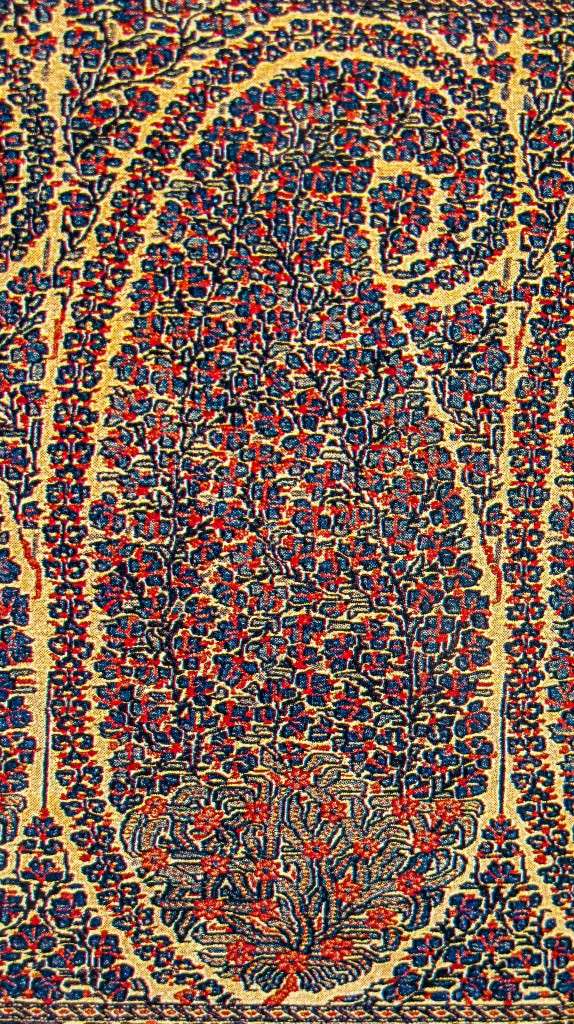

The boteh (Persian: بته), which is a Persian word for an almond or pine cone-shaped ornament with a sharp-curved upper end, is a common motif in the Near East, India, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and other countries. While it is of Persian origin, it is known as buta in India and has spread to Europe since at least the 19th century through Kashmir shawls. The patterns using this motif in Europe are known as paisleys, named after the town of Paisley in Scotland, which was a major centre for producing these shawls.

In Asian ornamentation, the boteh motifs are typically arranged in neat rows, but in India, they may appear in various sizes, colours, and orientations, which is also seen in European paisley patterns. Some design scholars suggest that the boteh is a combination of a stylized floral spray and a cypress tree, which is a Zoroastrian symbol of life and eternity. The “bent” cedar is also a symbol of strength, resistance, and modesty. The floral motif originated in the Sassanid dynasty and later in the Safavid dynasty of Persia (1501–1736) and was a popular textile pattern in Iran during the Qajar and Pahlavi dynasties. During these periods, the pattern was used to decorate royal regalia, crowns, court garments, as well as textiles used by the general population. In Persian and Central Asian designs, the motifs are usually arranged in orderly rows with a plain background.

The Sēnmurw Silk

Woven Silk

7th century to 8th century ©V&A

This patterned silk fragment with a green ground and greenish-yellow pattern shows the fabulous creature, the sēnmurw, enclosed in a roundel of pearls. Part bird, part beast, the sēnmurw is a creation of Sasanian art, although it was derived from more ancient Babylonian and Assyrian cultures, as well as from the sea-horse of Greek art.

Silk panel from Akhmim also dated to 7-8th cent. CE

In a 1999 article, Dr. Cyrus Parham notes that there are many notable examples of the boteh motif in both pre-Islamic and post-Islamic Iranian arts. The earliest appearances of the motif can be found in Scythian and Achaemenid art, where it was often depicted as the wings of Homa or Senmurv (Simorgh?). This usage continued until the Sassanian period. However, images of the Achaemenid and Scythian examples cited by Dr. Parham have unfortunately not been located.

The dry climate and sandy subsoil of Egypt allowed fabric to withstand the test of time better than many other regions. The earliest known samples of silk garment fragments adorned with what appears to be a precursor to the boteh motif were found in Akhmim, a city in Upper Egypt, dating back to the 6th-8th centuries CE. During the 6th to 8th centuries BCE, Akhmim, located on the banks of the Nile in Upper Egypt, was within the sphere of Greek influence and was known by Hellenized names such as Panopolis, Khemmis, or Chemmis. The motif discovered on the Akhmim fabrics is unique to the region and is not found elsewhere in Egypt. Although it was under Sassanian control for a brief period, Akhmim has intermittently been part of the Persian empire since the reign of Darius the Great (522-486 BCE). It is highly probable that Akhmim was situated at the western end of the Aryan trade roads, which were known as the Silk Roads.

The paragauda and clavus fragments made of silk were discovered in Akhmim’s cemeteries at the end of the 19th century CE. These fragments were parts of women’s tunics, with the paragauda being the border and the clavus being the circular decoration on the paragauda. The word paragauda is believed to have Indo-Iranian origins. The motifs found on the Akhmim fabrics are stylized oversized leaves or fruits attached to a tree or vine. The pointed dropping tips, sometimes with a sprayed tip, and the border around the motif encasing an internal design are consistent with the later unattached boteh motif.

According to Dr. Cyrus Parham, mentioned previously, there is evidence of a symbiotic relationship between the cypress and botteh motifs in art from the final years of the Sassanid period and the early Islamic era, suggesting that the ancient motif originated from the cypress . This specimen is of great significance in the evolution of the botteh because, despite the conspicuous emergence of this motif from the cypress in Iranian art of the 17th and 18th centuries , many art scholars tend to overlook this critical stage of ornamental and symbolic transformation.

Other articles on the boteh also link the motif to the Cypress and to the significance of the Cypress as a tree of life in Zoroastrian folkloric tradition. In addition, the boteh motif is sometimes referred to as the flame of Zoroaster. We are informed by Fiona Maclachlan that in Azerbaijan, the buta (botteh) is regarded as a symbol of fire.

Silk panel from Akhmim also dated to 7-8th cent. CE ©Nazmiyal Antique Rugs

The Sassanian culture, which existed between 224-651 CE in the land that later became Persia and modern-day Iran, introduced the cypress tree motif. The success of this empire was due, in part, to the social stratification reinforced by the Zoroastrian religion, as well as the influence of ancient Greek and Roman culture.Zoroastrianism is believed to have originated in ancient traditions predating its formal teachings and writings. The earliest form of Zoroastrian worship involved open-air gatherings on high mountains, featuring an urn with a fire flanked by two cypress trees reaching towards the sky. While later temple ceremonies were held in purpose-built structures, the cypress tree continued to play an important role. Cypress branches were often burned or placed on the altar, and the tree remains a symbol of eternity and long life in Zoroastrianism. This is due to the fact that cypress trees are evergreen and do not die back in winter, as well as being known as some of the longest-lived trees in the world. The cypress tree motif frequently appears in Zoroastrian folk art.

Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest organized religions, is an Iranian faith based on the teachings of Zoroaster, an Iranian-speaking prophet. Its dualistic cosmology divides the world into good and evil, with a monotheistic ontology and eschatology predicting the eventual triumph of good over evil. The religion venerates Ahura Mazda, an uncreated and benevolent deity of wisdom, as its supreme being. Zoroastrianism’s unique tenets, including its belief in messianism, monotheism, judgement after death, free will, and concepts of heaven, hell, angels, and demons, may have had an influence on other religious and philosophical systems, such as the Abrahamic religions, Gnosticism, Northern Buddhism, and Greek philosophy, throughout history.

The boteh motif exists in multiple forms, some of which may be interrelated and incorporated into a single design on various textiles, carpets, or engravings. The fragments of fabric found in Akhmim provide examples of several variations of the motif, including a twinned version resembling a stylized blossom. This variation is consistent with those found in Akhmim dating back to the 7th and 8th centuries CE.

Haji Piyada Mosque ḤĀJI PIĀDA or Noh Gonbad Mosque (Persian: مسجد نُهگنبد “Mosque of Nine Cupolas”), a Samanid-style building in Balkh province of northern Afghanistan. Built in the 9th century, it is thought to be the earliest Islamic building in the country. Carbon dating conducted in early 2017, together with historical sources, suggest it could have been built as early as the year 794.

The English word “shawl” is derived from the Persian word “shal,” which originally referred to a type of woven fabric rather than a specific article of clothing. This fabric could be used for various items such as scarves, turbans, mantles, or coverlets, but the common feature was the use of fine wool or other animal fleece. According to the Italian traveler Pietro della Valle, who wrote in 1623, the shawl was worn as a girdle in Persia, but in India, it was usually draped across the shoulders. This usage of the shawl as a shoulder-mantle made India the true home of the decorative shawl, as it was known in Europe. The shawl was typically a male garment in India, and its level of fineness was associated with nobility. Although this simple garment has a long history in the Near East, the finest shawls of the modern era are closely associated with Kashmir.

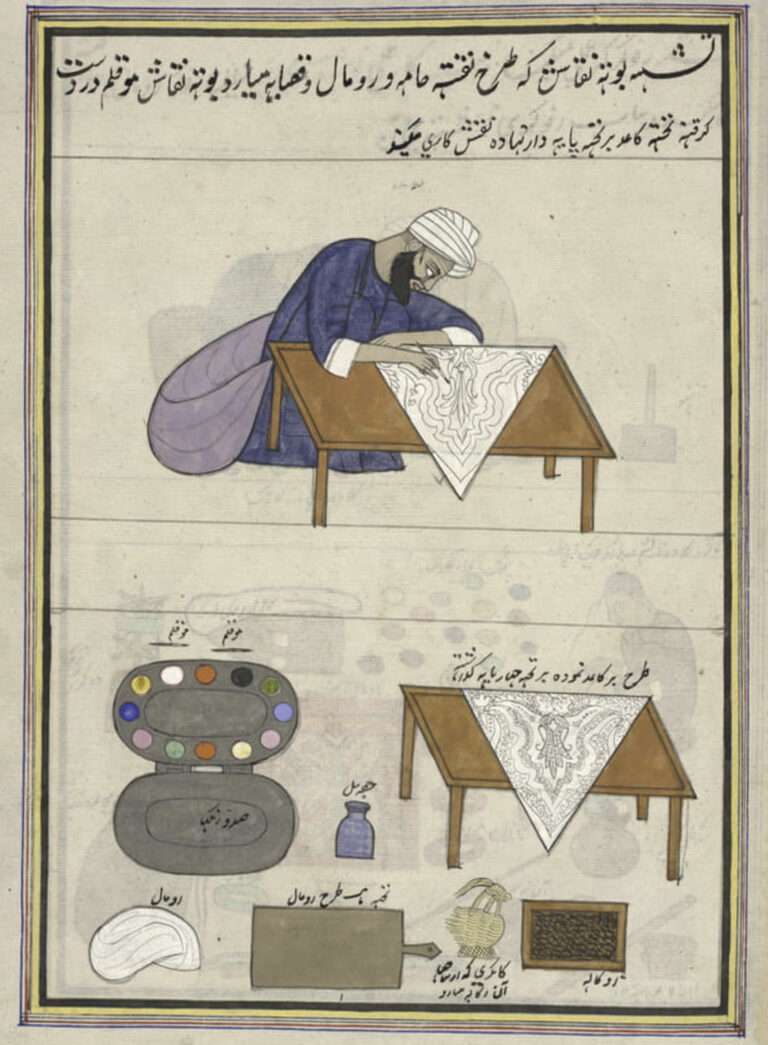

The origins of the Kashmir textile industry are not well documented. However, local legend suggests that it was founded by Zain-ul-’Abidin(A.D. 1420-70), who ruled Kashmir during the 15th century and brought Turkistan weavers to the region. While this claim remains unproven, it is notable that the industry in Kashmir differed from traditional weaving in India proper in terms of technique. This technique, known as the twill-tapestry technique, is similar to techniques used in Persia and Central Asia but is not found elsewhere on the Indian sub-continent. In this technique, wefts of the patterned part of the fabric are inserted using wooden spools called tojli, without the use of a shuttle. The pattern is formed solely by the weft threads and does not run the full width of the cloth. The Kashmir technique also differs from tapestry weaving in other ways, such as the horizontal loom and its operation being more like brocading.

The twill-tapestry technique used in shawl production was a slow and specialized process. Typically, the patterned portion of a shawl was woven on a single loom, while the plain field was woven on a separate loom with a shuttle. For complex designs, a shawl could take up to eighteen months to complete. However, in the early 19th century, new training methods and more intricate designs led to the introduction of dividing the work of a single shawl among multiple looms. By using this method, a design that would have taken one loom eighteen months could now be completed in nine months by two looms, or even faster by three or more looms. Once the various parts of the design were woven separately, a needleworker would join them together so skillfully that the joins were undetectable to the naked eye. This method of distributing work among multiple looms was described as a recent introduction in 1821, with some reports later in the century of shawls being assembled from as many as 1,500 separate pieces, often called “patchwork shawls”.

At the start of the nineteenth century, the amli or needle-worked shawl was a significant innovation that was entirely ornamented with the needle on a plain woven ground. However, even tilikar or loom-woven shawls were occasionally touched up by a rafugar or embroiderer responsible for reinforcing colors and occasionally modifying the design. The needle-worked shawl, which was unknown in Kashmir before the nineteenth century, was introduced by an Armenian named Khwaja Yusu, who came to Kashmir in 1803 as an agent of a Constantinople trading firm. Khawaja Yusuf realized that imitating the loom-woven patterns with the simpler process of needle-embroidery on a plain ground required much less time and skill, and consequently, less investment. With the help of a seamster named Ali Baba, he produced the first needle-worked imitations for the market at one-third of the cost of the loom-woven shawls. As a result, enormous profits were made, and this branch of the industry expanded rapidly. In 1823, the Government duty levied on the loom-woven shawl amounted to 26 percent of the value, which the needle-worked shawls initially avoided. This significant cost-saving led to the growth of this branch of the industry. In 1803, there were only a few rafugars or embroiderers with the necessary skill for the work, but twenty years later, there were estimated to be five thousand, many of whom were former landholders who were dispossessed of their property by Ranjit Singh in 1819 when Kashmir was invaded and annexed to the Sikh kingdom.

To create the ground for an amli or embroidered shawl, a cloth was placed on a plank and smoothed out by rubbing it with a polished agate or cornelian. The design was then transferred from paper to the cloth by pouncing with coloured powder or charcoal. Stem stitches were used for the needlework, which were made as flat as possible against the ground, similar to the woven patterns. Individual threads of the warp were carefully picked up in the stitching. According to Moorcroft, the needlework of the first amli shawls was less perfect and had a raised or embossed appearance similar to traditional Indian chain-stitch work. The improved method was later learned from embroiderers in the Kirman province of Persia.Throughout the nineteenth century, needle-worked shawls were made, many of which simulated loom-woven patterns, while others depicted scenes with human figures, which will be discussed later in the section on style. It is worth noting, however, that after 1850, the technique of many amli shawls, particularly those with human figures, deteriorated significantly, with some embroiderers resorting to a relatively coarse chain-stitch, sometimes executed on a cotton ground.

The Pattern-drawer (naqqash) and his implements.

Painted by a native artist, C. 1823.

Indian Office Library, Oriental Vol. 7

Kashmir shawls were historically woven using fleece from the Capra hircus, a central Asian mountain goat species. In the West, this wool was commonly known as pashmmina (from Persian pashm, meaning any wool) or cashmere, due to the old spelling of Kashmir. However, it is worth noting that all shawl wool used in Kashmir was imported from Tibet or Central Asia and was not locally produced. The fleece grew naturally as protection against the harsh winter climate of those regions and was found beneath the rough outer hair, with the finest quality coming from the underbelly. While goats were the primary source of shawl wool, a similar fleece was also obtained from wild Himalayan mountain sheep such as the Shapo (Ovis orientalis vignei blythi), the Argali (Ovis ammon linnaeus), and the Bharal (Pseudois nayaur hogson).

The fleece used in Kashmir shawls came in two distinct grades. The most prized and well-known was the asli tus, which was collected from wild animals and known for its softness, silkiness, and warmth. This grade was quite rare due to its scarcity and the time and effort required for its cleaning and spinning, and it made up only a small portion of the shawl-wool imports to Kashmir. However, it was this grade that was responsible for the famous “ring shawls” that were so fine they could be drawn through a thumb-ring. Only two looms in all of Kashmir specialized in weaving pure asli tus.

The second grade of shawl-wool was derived from domesticated goats of the same species and made up the bulk of the raw material used for weaving. Prior to 1800, most of it came from Ladakh and western Tibet, but after an epidemic among goats in these areas, supplies were sourced mainly from Kirghiz tribes and imported through Yarkand and Khotan. In the second half of the century, the main source became Turfan in Sinkiang, which was increasingly expensive and led to adulteration and lower quality standards. This was one of the factors that contributed to the decline of the shawl trade in the 1860s.

need to know the history of how the British ruled India.

The British rule in India began in 1757 with the Battle of Plassey, in which the British East India Company defeated the Nawab of Bengal and established its authority over the region. Over time, the British gradually expanded their territorial control through a combination of military conquest, alliances, and treaties with Indian rulers.The British introduced a system of indirect rule, whereby they appointed Indian princes and rulers as their local agents, known as “princely states,” to administer territories on their behalf. The British also introduced modern technologies, such as railways and telegraphs, which helped to integrate India’s diverse regions and economies.However, British rule in India was marked by economic exploitation, political suppression, and cultural oppression. The British imposed heavy taxes on Indian goods and industries, which led to the destruction of traditional Indian industries such as textiles. The British also used a divide-and-rule policy to maintain their hold on India, pitting different communities against each other and sowing discord and mistrust.

The Indian independence movement, led by figures such as Mahatma Gandhi, emerged in the early 20th century and sought to end British rule. After years of struggle and mass mobilization, India gained its independence in 1947, but not without the partition of the country into India and Pakistan, which led to widespread violence and displacement. Overall, the British rule in India lasted for nearly 200 years and had a profound impact on the country’s political, economic, and social systems. While the British introduced many modern technologies and institutions, their rule was also marked by exploitation and oppression, and the legacy of their rule continues to shape India’s development today.

Beginnings of the Paisley

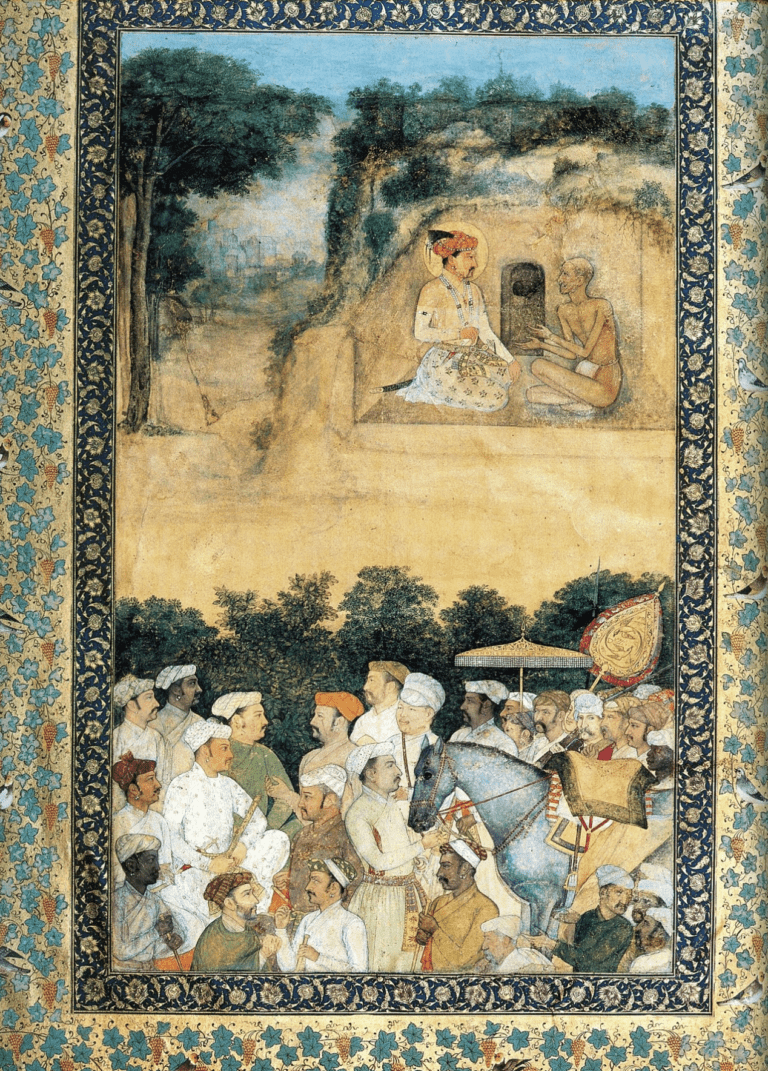

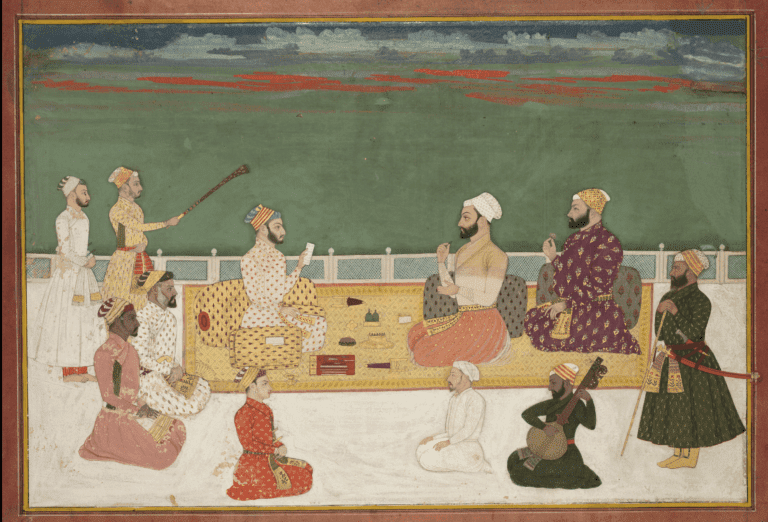

After conquering Kashmir in 1568, Akbar took a keen interest in the design and production of Kashmiri shawls as a symbol of love and regal status. He established workshops exclusively for the manufacture of Kashmiri shawls and provided specific instructions to his aides on the weaving and dyeing techniques. The evolution of the shawls continued through the centuries and eventually culminated in the well-known Paisley pine cone shape by the 19th century. The booming shawl trade played a significant role in popularizing the Paisley motif in Europe and other parts of the world. By the time Paisley gained popularity in Europe, the motif had reached its artistic and design zenith.The magnificent Paisley design we recognize today originated from the creativity of shawl makers in the 17th century, inspired by the Mughal Emperor Akbar’s reign, which saw a significant expansion in shawl production.

The Shawl Booming (Asian trade BC1500 – 1700)

british east india company (1600-1639)

In 1600, the British established the East India Company and sent its first merchant fleet to the Indian subcontinent in 1608, when it sent them to the north-west Indian port of Surat, where they obtained permission from Jahangir to trade on favourable terms.

In 1634, the English traders were welcomed to the Bengal region by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, and by 1717, customs duties were completely exempted for the English in Bengal. At that time, the main trades of the East India Company were cotton, silk, indigo dye, saltpetre, and tea. However, the Dutch were fierce competitors who had already extended their monopoly on the spice trade in the Straits of Malacca by driving out the Portuguese between 1640 and 1641. With diminished Portuguese and Spanish influence in the area, the East India Company and the Dutch East India Company engaged in intense competition, leading to the Anglo-Dutch Wars in the 17th and 18th centuries.

In 1639, the East India Company acquired the land from the lords of Chennai, and was allowed to build a fortress, and at the same time, the British East India Company was exempted from customs duties in its trade in the area, and if any other company traded, half of the duties levied on it by the British East India Company would be The name was changed to Madras and a foothold in Indian trade was established.

Buta on Kashmiri Shawls (BC1700-1730)

The early 18th century was a period of significant political change in India. The Mughal Empire, which had ruled India since the 16th century, was in a state of decline, with weak emperors and regional governors asserting greater independence. This created a power vacuum, which was filled by various regional powers, including the Marathas, the Sikhs, and the Nawabs of Bengal, Hyderabad, and Awadh.The Marathas, a Hindu warrior caste, rose to power under the leadership of Shivaji, who established an independent Maratha kingdom in western India. After Shivaji’s death in 1680, the Marathas continued to expand their territory and influence under the leadership of his son, Sambhaji, and grandson, Chhatrapati Shahu.

The Sikhs, a religious community that had emerged in the Punjab region in the late 15th century, also gained political power during this period. The Sikh leader, Banda Singh Bahadur, led a rebellion against Mughal rule in the early 1700s and established a short-lived Sikh state in the Punjab.Meanwhile, the Nawabs of Bengal, Hyderabad, and Awadh became increasingly powerful and independent of Mughal control. They established their own administrations and armies, and by the mid-18th century, they had become some of the wealthiest and most powerful rulers in India.Overall, the period between 1700 and 1730 in India was marked by the decline of the Mughal Empire and the rise of regional powers, which would ultimately lead to the fragmentation of India and the emergence of European colonialism in the subcontinent.

The shawl industry experienced a slight decline towards the end of the 19th century, but the enduring appeal of Kashmir shawls remained undiminished. Today, they continue to be popular, and although they are more widely available, they have lost none of the extravagant charm that made them the choice of royalty in Europe and Asia. The Paisley motif has also stood the test of time, and today its timeless allure and representation of love can be found in everything associated with high fashion, elegance, and luxury. Kashmir has rightfully reclaimed its position as the originator of the Paisley design, and shawl enthusiasts now rely on guardians of shawl-making tradition to supply them with the finest Kashmir Paisley shawls. The Kashmir Company remains a part of this rich history, and the intricate and timeless Paisley design is an essential element of our exclusive collection of shawls.

Buta on Kashmiri Shawls (BC1740-1770)

The Industrial Revolution in Britain (1764)

The Industrial Revolution in Britain was a period of rapid industrialization that took place from the late 18th to the mid-19th century. It was characterized by a series of technological and economic advancements that transformed the way goods were produced and consumed, and had a profound impact on social, economic, and political structures. The cotton industry played a significant role in this transformation, and was one of the key drivers of the Industrial Revolution.

Buta on Kashmiri Shawls (bc 1770-1800)

Buta on Kashmiri Shawls (bc 1810)

Kashmir jacket, 1803. ©V&A Museum

Kashmir shawl, early 1800s. © V&A Museum

Portrait of a nobleman or royal figure, possibly Muhammad Shah Qajar

Mohammad Shah Qajar was the fifth king of the Qajar dynasty, which ruled Persia (now Iran) from 1785 to 1925. He was born on January 5, 1808, in Tabriz, Iran, and became the king of Persia in September 1834, following the death of his father, Fath Ali Shah.During his reign, Mohammad Shah faced numerous challenges, including political instability, economic difficulties, and territorial disputes with neighboring countries. He also faced several rebellions, including the Mazandaran Uprising of 1837, which was suppressed with the help of Russian troops.

One of the most significant events of Mohammad Shah’s reign was the Treaty of Turkmenchay, which was signed in 1828 between Persia and Russia. The treaty ended the Russo-Persian War of 1826-1828 and resulted in Persia ceding control of much of its territory in the Caucasus to Russia.Mohammad Shah also initiated a number of reforms during his reign, including the modernization of the military, the establishment of a postal system, and the introduction of European-style clothing and education. However, these reforms were met with resistance from traditionalists and conservative elements within Persian society.Mohammad Shah died on September 5, 1848, and was succeeded by his son, Naser al-Din Shah Qajar. Despite the challenges he faced during his reign, Mohammad Shah is remembered as an important figure in Iranian history and as a patron of the arts, particularly music and poetry.

Buta on Kashmiri Shawls (bc 1820-1830)

Amidst this context, the Bengal Renaissance emerged as a significant cultural and intellectual movement that played a crucial role in shaping modern India. The Bengal Renaissance, which began in Bengal in the late 18th century, reached its peak during the 1820s and 1830s. It was characterized by a renewed interest in Bengali language, literature, and culture and led to the emergence of a new generation of thinkers, writers, and artists who sought to create a distinct identity for India.

However, the period was also marked by political upheavals, including the Indian Mutiny, also known as the First War of Independence, which broke out against British rule in 1857. While the events leading up to the rebellion occurred over a period of time, it is often considered to have begun in 1824 when the British introduced a new rifle to their Indian soldiers that required them to bite off the ends of greased cartridges, which were rumored to be coated with cow and pig fat. This was deeply offensive to Hindu and Muslim soldiers, who considered cows and pigs to be sacred and unclean, respectively. The ensuing revolt was a turning point in India’s struggle for independence and marked the beginning of the end of British rule in India.The opium trade was another significant development during this period. The British continued to trade opium from their colonies in India to China, causing tension between the two nations and leading to the Opium Wars (1839-1860). The opium trade had devastating consequences for China, leading to addiction, social upheaval, and economic decline.

Finally, the period between 1820 and 1830 also witnessed significant modernization and infrastructure development in India. The British invested in building railroads and telegraph lines, which helped to connect India’s various regions and facilitate trade and communication. However, these developments were often focused on serving British interests rather than the needs of Indian people, and the benefits of modernization were unevenly distributed.

Hindu woman from Bombay wearing a Kashmir shawl