HISTORICAL

About the Industrial Revolution

August – 2023 20 MINS READ

We tend to focus on ‘invention’ and ‘population’ when talking about the Industrial Revolution. But we must know that history does not happen from those dots, but from a number of multiple factors. We will discuss the most important ‘invention’ in final chapter. Before that, let’s get to know the historical background that happened around it and follow the history of why the Industrial Revolution was able to become a thing in the UK.

産業革命を語るときに、私たちは「発明」と「人口」という点の部分に焦点を当てがちです。しかし歴史はそれらの点から起こるのではなく、いくつもの複合的な要因から起こっていることを知らなければなりません。そこで今回は最も重要な「発明」については最終章で述べることにします。その前にその周辺で起こった歴史的背景を知り、なぜイギリスで産業革命が起こったのか? その歴史を追ってみましょう。

The “revolution” traditionally refers to a popular uprising marked by forceful rhetoric and actions, seeking beneficial changes for humanity. The Industrial Revolution, in contrast, lacked grand speeches, conventions, or battles. Nonetheless, this silent revolution profoundly transformed the lives of millions, making it arguably the greatest revolution in history. It heralded the end of the past civilization and the dawn of the present and future civilization.A contemporary author aptly describes this transformation as having completely reshaped modern Europe and the new world. It gave rise to a new breed of individuals—those who worked with machines instead of their hands, congregated in cities rather than residing in scattered villages, and engaged in international trade as effortlessly as local commerce. Their workshops harnessed the power of nature, replacing manual labor, and their market extended beyond city or country boundaries to encompass the entire world.

MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY EUROPEAN HISTORY / jacob sALWYN SCHAPIRO, Ph.D. 1917

「革命」とは伝統的に、人類にとって有益な変化を求める力強い発想や行動を特徴とする民衆蜂起を指すことが多いです。これとは対照的に「産業革命」には壮大な演説も大会も戦いもありませんでした。それにもかかわらずこの静かな革命は何百万人もの人々の生活を大きく変え間違いなく歴史上最大の革命になりました。ある現代作家はこの変革が近代専制君主性ヨーロッパと新世界を完全に分断・再構築したと的確に表現しています。手の代わりに機械を使って働き、散らばった村に住むのではなく都市に集まり、国際貿易を地域商業と同じように難なくこなしていく。彼らの工房は自然の力を利用し、手作業に取って代わりその市場は都市や国を越えて全世界に広がっていきました。

近代・現代ヨーロッパ史 / ヤコブ・サルウィン・シャピロ博士 1917

The British Agricultural Revolution

The British Agricultural Revolution (also called the Second Agricultural Revolution) led to an unprecedented surge in agricultural production in Britain from the mid-17th to the late 19th centuries. This remarkable growth was primarily driven by significant increases in labor and land productivity. Over a hundred years, until 1770, agricultural output outpaced population growth, resulting in one of the highest productivity rates in the world. The surplus of food contributed to the rapid population expansion in England and Wales, which soared from 5.5 million in 1700 to over 9 million by 1801. However, in the 19th century, as the population more than tripled to over 35 million, the reliance on food imports escalated, overshadowing domestic food production.

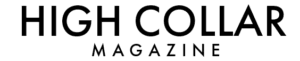

Using 1700 as a benchmark (represented as 100), the output per agricultural worker in Britain exhibited steady growth, ascending from approximately 50 in 1500 to 65 in 1550, 90 in 1600, over 100 by 1650, and surpassing 150 by 1750. The momentum continued, rapidly escalating to over 250 by 1850. As agricultural productivity increased, the share of the agricultural labor force declined, leading to a burgeoning urban workforce that was vital for industrialization. As a result, the Agricultural Revolution is often cited as one of the catalysts for the subsequent Industrial Revolution.

The agricultural revolution led to an influx of people into urban areas in the UK. The agricultural revolution led to a significant increase in agricultural productivity, which meant that fewer people were needed to work in the agricultural sector. This freed up people to move to urban areas, where there were more opportunities for employment in the manufacturing and service sectors.The influx of people into urban areas led to the growth of cities, and the development of new industries and services. This was a major factor in the Industrial Revolution, which began in the UK in the late 18th century.

イギリス農業革命(第二次農業革命とも呼ばれる)は、17世紀半ばから19世紀後半にかけて、イギリスの農業生産量に前例のない急増をもたらしました。この驚くべき成長は、主に労働力と土地生産性の大幅な向上によってもたらされました。1770年までの100年間、農業生産量は人口増加を促し世界でも有数の生産率を達成しました。この余剰食料は、イングランドとウェールズの人口が1700年の550万人から1801年には900万人以上へと急増する原動力となりました。しかし、19世紀になると、人口が3500万人以上と3倍以上に増加したため、食料輸入への依存度が高まり、国内の食料生産が影を潜めました。1700年を基準(100として表記)として、イギリスの農業従事者一人当たりの収量は、1500年には約50から、1550年には65、1600年には90、1650年には100を超え、1750年には150を超えました。この勢いは続き、1850年には250を超えるまで急上昇しました。農業生産性が向上するにつれて、農業労働力比率は低下し、産業化に不可欠な急成長する都市労働力につながりました。その結果、農業革命はしばしばその後の産業革命の触媒の1つとして引用されます。

農業革命は、イギリスで多くの人々が都市部に移住する原因となりました。農業革命は農業生産性を大幅に向上させ、農業分野で働く必要のある人数が少なくなったことを意味します。これにより、製造業やサービス業でより多くの雇用機会がある都市部に移住する人々が解放されました。都市部への人々の流入は、都市の成長と新規産業・サービスの発展につながりました。これは、18世紀後半にイギリスで始まった産業革命の主要な要因の1つでした。

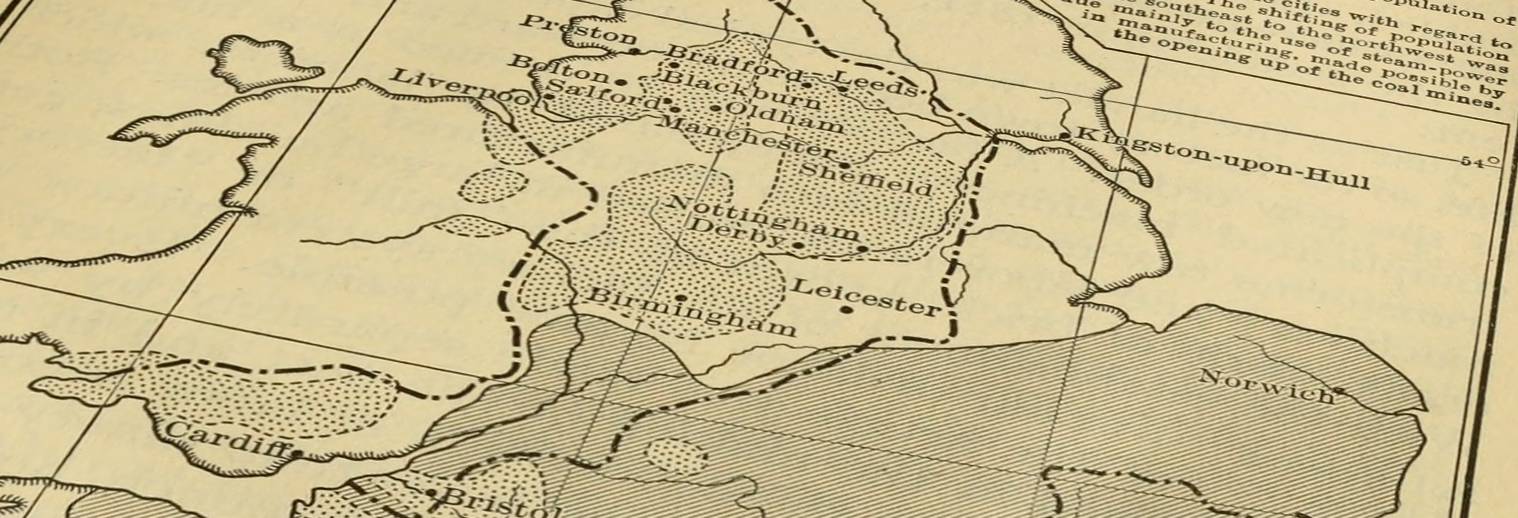

Norfolk four-course system

The Norfolk four-course system is an agricultural technique that centers around crop rotation. Unlike earlier methods like the three-field system, the Norfolk system does not include a fallow year. Instead, it follows a four-year cycle, in which four distinct crops are cultivated annually: wheat, turnips, barley, and either clover or undergrass. Originating in the early 16th century in the region of Waasland (present-day northern Belgium), the system gained popularity in the 18th century thanks to the efforts of British agriculturist Charles Townshend. The sequence of crops, which includes wheat, turnips, barley, and clover, incorporates a fodder crop (turnips) and a grazing crop (clover), allowing livestock to be raised throughout the year. The Norfolk four-course system played a pivotal role in driving the British Agricultural Revolution and facilitated a rotation between arable and ley, which is often referred to as ley farming.

ノーフォーク4年法は、輪作を中心にした農業技術です。3圃場法などの以前の方法とは異なり、ノーフォーク法は休耕年がありません。代わりに、小麦、カブ、大麦、クローバーまたは下草の4つの異なる作物を毎年栽培する4年周期に従います。このシステムは、16世紀初頭にベルギー北部にあるワッセランド地方で生まれました。18世紀には、イギリスの農学者チャールズ・タウンゼンドの努力により、このシステムは人気を博しました。小麦、カブ、大麦、クローバーの4つの作物は、飼料作物(カブ)と放牧作物(クローバー)を組み入れており、一年中家畜を飼育することができます。ノーフォーク4年法は、イギリスの農業革命に重要な役割を果たし、耕地と草地の間(しばしば草地農業と呼ばれる)の輪作を促進しました。

CALICO

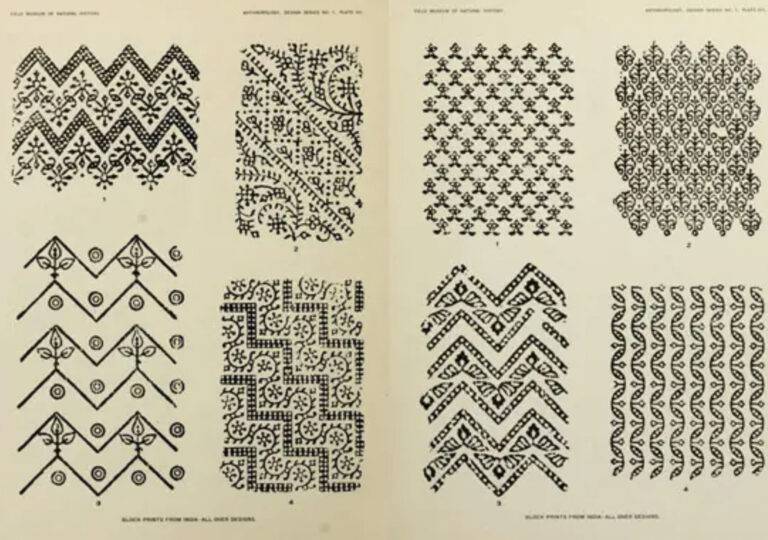

Calico/ˈkælɪkoʊ/, a term in use since 1505 in British English, refers to a sturdy, plain-woven textile crafted from unbleached cotton that is often left partially untreated. Additionally, it may contain unseparated husk parts. This fabric’s texture is coarser than muslin but less rough and thick compared to canvas or denim, making it quite affordable due to its unfinished and undyed appearance.

Originally hailing from the city of Calicut in southwestern India, calico was produced by skilled traditional weavers known as cāliyans. These weavers would dye and print the raw fabric in vibrant colors, which eventually gained popularity in Europe as calico prints.

Calico originated in Calicut, from which the name of the textile came, in South India, now Kerala, during the 11th century,where the cloth was known as “chaliyan”. It was mentioned in Indian literature by the 12th century when the polymath and writer Hemachandra described calico fabric prints with a lotus design. Calico was woven using Gujarati cotton from Surat for both the warp and weft. By the 15th century, calico from Gujarat made its appearance in Cairo, then capital of the Egypt Eyalet under the Ottoman Empire. Trade with Europe followed from the 17th century onwards.

Calicut had a strongly independent clan king and prospered as the centre of the Muslim trading network. The Portuguese Vasco da Gama fleet arrived there in 1498, and in the early 16th century Portugal eliminated the Muslim power in the Indian Ocean by force and promoted a monopoly on Indian trade, mainly the the spice trade, but gradually lost their monopoly to the subsequent Dutch and British. When British rule in India was eventually established, Calicut also became a British territory in 1792. The name Calicut was used in English during the British colonial period, and is now written as Kozhikode (or Kohlikode), the local pronunciation of the name. Note that Calcutta (now Kolkata) is a city in the Bengal region of eastern India, where the British were based.

英語で1505年から使われているCalicoは、未漂白のコットンで織られた丈夫な平織りの織物を指します。また、未分離のコットン糸くず(ネップ)が含まれていることもあります。この生地の質感はモスリンよりも粗いが、キャンバスやデニムに比べると粗さや厚みは少なく染色されていない外観のためかなり手頃な価格となっていました。もともとはインド南西部のカリカット市で生まれたキャラコは、カーリヤンと呼ばれる熟練した伝統的な織り手によって生産されていました。キャリコの起源は、11世紀に南インドのカリカット(現在のケララ州)で生まれた織物で、「チャリヤン」と呼ばれていました。12世紀にはインド文学に登場し、博学で作家でもあったヘマチャンドラが蓮をデザインしたキャラコ織物について記述しています。キャラコは経糸と緯糸の両方にスラート産のグジャラート綿を使って織られていました。15世紀にはグジャラート産のキャラコが、オスマン帝国下のエジプト・エヤレットの首都だったカイロに登場した。17世紀以降はヨーロッパとの貿易が始まりました。

カリカットには独立したイスラム教徒の交易網の中心地として栄えました。1498年にポルトガルのヴァスコ・ダ・ガマ艦隊が到着し、16世紀初頭、ポルトガルはインド洋におけるイスラム勢力を武力で排除、香辛料貿易を中心とするインド貿易の独占を推進しましたが、次第にその後のオランダ、イギリスに独占を奪われていきました。やがてイギリスのインド支配が確立すると、1792年にはカリカットもイギリス領になりました。カリカットという地名はイギリス植民地時代に英語表記されたもので、現在では現地の発音であるコジコデ(またはコーリコデ)と表記される。なお、カルカッタ(現コルカタ)は、イギリスが拠点としていたインド東部のベンガル地方の都市である。

Port city on the west coast of India. Muslim merchants, Zheng He sent by the Yongle Emperor, and later Vasco-da-Gama of Portugal visited the city. It is now called Kozhikode in the local language.

CALICO ACT

During the 18th century, England became renowned for its thriving woollen and worsted cloth industry, which was predominantly centered in the eastern and southern regions, including towns like Norwich. The manufacturers of this industry zealously guarded their products. In contrast, the cotton processing sector was relatively small, with meager imports of cottonwool into England. In 1701, only 900,775 kilograms (1,985,868 lb) of cottonwool were imported, and by 1730, this figure declined further to 701,014 kg (1,545,472 lb) due to protective commercial legislation favoring the woollen industry.

During the 18th century, England became renowned for its thriving woollen and worsted cloth industry, which was predominantly centered in the eastern and southern regions, including towns like Norwich. The manufacturers of this industry zealously guarded their products. In contrast, the cotton processing sector was relatively small, with meager imports of cottonwool into England. In 1701, only 900,775 kilograms (1,985,868 lb) of cottonwool were imported, and by 1730, this figure declined further to 701,014 kg (1,545,472 lb) due to protective commercial legislation favoring the woollen industry.

Over time, cottonwool imports rebounded and reached nearly the same levels as in 1701 by 1720. However, Coventry woollen manufacturers claimed that these imports were displacing their workers’ jobs. In response, the Woollen, etc., Manufactures Act 1720 was passed, imposing fines on anyone found wearing printed or stained calico muslins, but exempting neckcloths and fustians. Lancashire manufacturers cleverly took advantage of this exemption and continued to produce colored cotton weft with linen warp, a combination specifically permitted by the 1736 Manchester Act.

By 1764, the import of cottonwool had surged to 1,755,580 kg (3,870,392 lb). The shift in consumption patterns resulting from restrictions on imported finished goods significantly impacted the Indian economy, leading to a decline in its sophisticated textile production and relegating it to being primarily a supplier of raw materials. These events occurred during colonial rule, which began in 1757 and were characterized by Nehru and some later scholars as a process of “de-industrialization.

18世紀、イギリスは、ノリッジなどの東部および南部地域を中心に、羊毛織物と毛織物産業が盛んで、その製造業者は熱心に製品を守っていました。対照的に、綿花加工部門は比較的小規模で、イギリスへの綿花の輸入はわずかでした。1701年には、わずか90万7,750キログラム(198万5,868ポンド)の綿花が輸入され、1730年までに、羊毛産業を優遇する保護的な商業立法により、この数字はさらに70万1,014キログラム(154万5,472ポンド)に減少しました。 東インド会社がインドから持ち込んだ安価なカリコプリントの人気が高まりました。これを受けて、議会は1700年に、インド、中国、ペルシャからの染色または印刷されたカリコの輸入を禁止する法律を制定しました。その結果、需要は未完成のカリコに移りました。これは、染色や印刷されていない灰色の布です。これらの灰色の生地は後に南部イングランドで人気のある模様で飾られました。ランカシャーの起業家は、麻の縦糸と綿の横糸で作られた生地であるフューステンを製造し、仕上げのためにロンドンに送りました。

時が経つにつれて、綿花の輸入は回復し、1720年までに1701年と同じレベルに近づきました。しかし、コヴェントリーの羊毛織物メーカーは、これらの輸入が彼らの労働者の仕事を奪っていると主張しました。これを受けて、1720年の羊毛製造等法が可決され、印刷物や染料で汚れたカリコのムースリンを見つけた人には罰金を科しましたが、ネクタイやフューステンを除外しました。ランカシャーのメーカーは巧みにこの免除を利用し、1736年のマンチェスター法で特に許可されている麻の縦糸と綿の横糸で色付きの綿の横糸を作り続けました。

1764年までに、綿花の輸入は1,755,580キログラム(3,870,392ポンド)に急増しました。輸入完成品の規制による消費パターンの変化は、インド経済に大きな影響を与え、その洗練された繊維生産は衰退し、最終的には主に原材料の供給源に追いやられました。これらの出来事は、1757年に始まった植民地支配下で起こり、ネルーや一部の後の学者によって「非工業化」のプロセスとして特徴づけられました。

– recommendation –

The world's best cotton has disappeared

The muslin fabric featured in Marie-Antoinette’s portraits. The sheer, transparent fabric fascinated European aristocrats. And the lost world best beautiful fabric “Dhaka Muslin” from Mughal Empire (Now Bangladesh) , They can no longer be reproduced. The craftsmen who made the delicate fabric had their fingers chopped off by the British man.

the Industrial Revolution

1698 THOMAS SAVERY / THE FIRST STEAM ENGINE

Thomas Savery was born in Shilstone manor house near Modbury, Devon. He was a military engineer who reached the rank of captain by 1702. In his spare time, he experimented with mechanics and secured patents for a machine to polish glass or marble and a ship propulsion mechanism using paddle-wheels driven by a capstan. However, the Admiralty rejected the latter invention due to a negative report by the Navy’s Surveyor, Edmund Dummer. In addition to his engineering ventures, Savery served the Sick and Hurt Commissioners, who were responsible for supplying medicines to the Navy Stock Company, which had connections with the Society of Apothecaries. This role led him to Dartmouth, Devon, where he likely met Thomas Newcomen.

トーマス・セイヴリーは、デヴォン州モドベリー近くのシルストンマナーハウスで生まれました。彼は軍事エンジニアであり、1702年までに大尉の階級に達しました。余暇には、機械工学を研究し、ガラスや大理石を磨く機械と、キャプスタンで駆動されるパドルホイールを使用する船の推進メカニズムに関する特許を取得しました。しかし、海軍の検査官であるエドマンド・ダマーの否定的な報告のため、後者の発明は海軍省によって拒否されました。エンジニアリング事業に加えて、セイヴリーは、海軍株会社に薬を供給する責任を負っていた病気と怪我の委員会を務めました。この会社は、薬剤師協会とつながりがありました。この役割により、彼はデヴォン州ダートマスに行き、そこでトーマス・ニューコメンと会った可能性があります。

Steam-powered pump

On July 2, 1698, Thomas Savery was granted a patent for a groundbreaking steam-powered pump, which he called “A new invention for raising water and generating motion for various mill work using the impellent force of fire.” The term “engine” was used in its contemporary sense, denoting any device or contrivance. Savery demonstrated the engine to the Royal Society on June 14, 1699.

The Savery engine was a pistonless pump with very few moving parts, the most important of which were the taps. The engine worked by first generating steam in the boiler. The steam was then directed into one of the working vessels, where it expelled water through a downpipe. Once the system was sufficiently heated and filled with steam, the tap between the boiler and the working vessel was closed. If necessary, the vessel’s exterior was cooled to condense the steam inside, creating a partial vacuum. Atmospheric pressure then pushed water up the downpipe until the vessel reached its full capacity. Subsequently, the tap below the vessel was shut, and the tap between it and the up-pipe was opened to admit more steam from the boiler. As steam pressure increased, it forced the water from the vessel up the up-pipe to the top of the mine.

However, Savery’s pump encountered several significant challenges. Firstly, a considerable amount of heat was wasted each time water was introduced into the working vessel, as it warmed up the water being pumped. Secondly, the pump’s soldered joints were barely capable of withstanding high-pressure steam, necessitating frequent repairs. Thirdly, although the pump utilized positive steam pressure to raise water (theoretically allowing for limitless vertical elevation), practical and safety considerations required the use of a series of moderate-pressure pumps at various levels to clear water from deep mines. Lastly, the pump relied on atmospheric pressure to push water up (working against a condensed-steam ‘vacuum’), which limited its effective height to approximately 30 feet (9.1 m) above the water level. This constraint mandated the pump’s installation, operation, and maintenance deep within the dark mines.

1698年7月2日、トーマス・セイヴリーは、画期的な蒸気式ポンプの特許を取得しました。彼はこれを「火の推進力を利用して、水を揚水し、さまざまな工場の動力を得る新たな発明」と名づけました。当時の「エンジン」という言葉は、あらゆる装置や仕組みを意味していました。セイヴリーは、1699年6月14日にロイヤル・ソサエティでこのエンジンをデモンストレーションしました。セイヴリー式エンジンはピストンのないポンプで、動きの部分はごくわずかです。最も重要な部分は、タップです。このエンジンは、まずボイラーで蒸気を発生させます。蒸気は、次に作業用容器に送り込まれ、水を下水管から排出します。システムが十分に加熱され、蒸気で満たされると、ボイラーと作業用容器の間の栓が閉じられます。必要に応じて、容器の外部を冷却して内部の蒸気を凝縮させ、部分的な真空を作成します。大気圧が下水管を通り、容器が満杯になるまで水を押し上げます。その後、容器の下にある栓が閉じられ、容器と上水管の間の栓が開いて、ボイラーからさらに蒸気が入ります。蒸気圧が増加すると、水が容器から上水管を経由して坑道の頂上まで押し上げられていきます。しかし、セイヴリー式ポンプにはいくつかの重大な課題がありました。まず、水が作業用容器に導入されるたびに、ポンプは多くの熱を無駄にしました。これは、ポンプされた水を温めてしまうためです。第二に、ポンプのはんだ付けされた接合部は高圧蒸気に耐えられるほど強度がないため、頻繁に修理が必要でした。第三に、ポンプは正の蒸気圧を利用して水を揚水するため(理論的には垂直方向の揚水に制限はありません)、深い坑道から水を排出するには、さまざまな高さに配置された一連の低圧ポンプを使用する必要があります。第四に、ポンプは、凝縮した蒸気の「真空」と相反する大気圧を利用して水を押し上げるため、水面から約30フィート(9.1 m)以上は揚水できませんでした。この制約により、ポンプの設置、操作、保守は暗い坑道の奥深くで行う必要がありました。

Fire Engine Act

In July 1698, Thomas Savery was granted a patent for his revolutionary steam pump. The following year, in 1699, an Act of Parliament was enacted to extend his protection for an additional 21 years. This act, known as the “Fire Engine Act,” was designed to promote and support Savery’s steam pump, which could be used for water-raising and mill work. Architect James Smith of Whitehill obtained a license to use Savery’s pump in Scotland. He claimed to have modified the machine to pump water from a depth of 84 feet.

Savery’s patent in England led to a partnership between him and Thomas Newcomen. By 1712, they had developed a more advanced steam engine design, which was marketed under Savery’s patent. This improved version included water tanks and pump rods, which allowed it to be used in deeper water mines. Newcomen’s engine used atmospheric pressure, which eliminated the risks associated with high-pressure steam. It employed the piston concept invented by Denis Papin, which resulted in the first steam engine capable of efficiently raising water from deep mines. Upon Savery’s death in 1715, his patent and Act of Parliament were transferred to a company called the “Proprietors of the Invention for Raising Water by Fire.” This company granted licenses to others for constructing and operating Newcomen engines, charging substantial patent royalties. The Fire Engine Act remained in effect until 1733, four years after Newcomen’s passing.

1698年7月、トーマス・セイヴリーは彼の画期的な蒸気ポンプの特許を取得しました。翌年の1699年、彼の保護をさらに21年間延長する法律が制定されました。この法律は「火力機関法」として知られ、水の揚水や工場の動力に使用できるセイヴリーの蒸気ポンプを促進および支援することを目的としていました。スコットランドの建築家、ホワイトヒルのジェームズ・スミスは、セイヴリーのポンプをスコットランドで使用するためのライセンスを取得しました。彼は、この機械を84フィートの深さから水を汲み上げるように改造したと主張しました。

セイヴリーのイギリスの特許は、彼とトーマス・ニューコメンのパートナーシップにつながりました。1712年までに、彼らはセイヴリーの特許の下で販売された、より高度な蒸気エンジンの設計を開発しました。この改良版には、水タンクとポンプロッドがあり、深い水の鉱山で使用できるようになりました。ニューコメンのエンジンは、高圧蒸気と関連するリスクを排除する大気圧を使用しました。それは、デニス・パパンが発明したピストン概念を採用し、深い鉱山から効率的に水を汲み上げることができる最初の蒸気エンジンとなりました。セイヴリーの死後、彼の特許と法律は「火力で水を揚水する発明の所有者」と呼ばれる会社に移管されました。この会社は、ニューコメンエンジンの建設と操作を許可するライセンスを他者に付与し、多額の特許使用料を請求しました。火力機関法は、ニューコメンの死から4年後の1733年まで施行されていました。

1733 JOHN KAY / THE FLYING SHUTTLE

John Kay (17 June 1704 – c. 1779) was an English inventor whose most important creation was the flying shuttle, one of the key contributions to the Industrial Revolution. He is often confused with another inventor named John Kay, who built the first “spinning frame.” Kay apprenticed to a hand-loom reed maker, but is said to have returned home within a month claiming to have mastered the business. He designed a metal substitute for the natural reed, which proved popular enough for him to sell throughout England. After traveling the country, making and fitting wire reeds, he returned to Bury and, on 29 June 1725, both he and his brother, William, married Bury women. John’s wife was Anne Holte. His daughter Lettice was born in 1726, and his son Robert in 1728.In Bury, he continued to design improvements to textile machinery. In 1730, he patented a cording and twisting machine for worsted.

In 1733, he received a patent for his most revolutionary device: a wheeled shuttle for the hand loom. It greatly accelerated weaving by allowing the shuttle carrying the weft to be passed through the warp threads more quickly and over a greater width of cloth. It was designed for the broad loom, which saved labor over the traditional process by requiring only one operator per loom (before Kay’s improvements, a second worker was needed to catch the shuttle). Kay always called this invention a “wheeled shuttle,” but others used the name “fly-shuttle” (and later, “flying shuttle”) because of its continuous speed, especially when a young worker was using it in a narrow loom. The shuttle was described as traveling at “a speed which cannot be imagined, so great that the shuttle can only be seen like a tiny cloud which disappears the same instant.

ジョン・ケイ(1704年6月17日 – 1779年頃)は、イギリスの発明家で、飛梭(ひしょう)を発明したことで知られています。飛梭は、産業革命を推進する上で重要な役割を果たしました。(ケイは、しばしば別の発明家であるジョン・ケイと混同されます。このジョン・ケイは、最初の「 spinning frame(紡績機)」を製作した人物です。)

ケイは手織り用の小型手織り機職人の見習いとして修行しましたが、1か月で手織り機を辞し商売を独学でマスターしたとされています。彼は手織り機に代わる金属製の手織り機を設計し、これが好評を博し、イングランド全土で販売されました。その後、ケイはイングランド中を旅して、金属製の手織り機を製造・販売しました。1725年6月29日、彼と彼の弟のウィリアムは、バーリーで地元の女性と結婚しました。ジョンの妻はアン・ホルテでした。彼の娘のレティシアは1726年に、息子のロバートは1728年に生まれました。バーリーで、ケイは繊維機械の改良を続けました。1730年、彼は Worsted(一種の毛織物)用のコーディングとツイストマシンを特許出願しました。1733年、彼は最も画期的な機械の特許を取得しました。それは、手織り機用の車輪付きのシャトル=梭(ひ)です。この梭は、織り機の速度を大幅に向上させ、より多くの幅の布を織ることができるようになりました。このシャトルは、従来の織り機に必要な2人ではなく、1人だけで操作できるため、労力を節約することができました。ケイは、この発明を「車輪付きのシャトル」と呼んでいましたが、他の人々は、特に狭い織り機で若い労働者が使用したときに、その連続した速度から「フライシャトル」や「フライングシャトル」と呼びました。このシャトルは、「想像を絶する速度で、シャトルは小さな雲のように見え同じ瞬間に消えてしまう」と形容されています。

1764 JAMES HARGREAVES / THE SPINNING JENNY

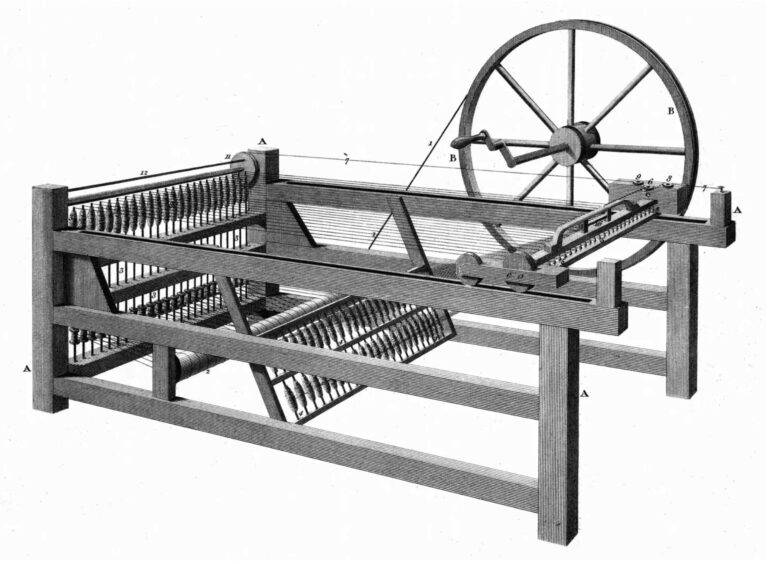

James Hargreaves (c. 1720 – 22 April 1778) was an English weaver, carpenter, and inventor who lived and worked in Lancashire, England. He was one of three men responsible for the mechanisation of spinning: Hargreaves is credited with inventing the spinning jenny in 1764; Richard Arkwright patented the water frame in 1769; and Samuel Crompton combined the two, creating the spinning mule in 1779.

The idea for the spinning jenny is said to have come when a one-thread spinning wheel was overturned on the floor, and Hargreaves saw both the wheel and the spindle continuing to revolve. He realized that if several spindles were placed upright and side by side, several threads could be spun at once. The spinning jenny was only able to produce cotton weft threads, and was not able to produce warp yarn of sufficient quality. A high-quality warp was later supplied by Arkwright’s spinning frame.Hargreaves built a jenny for himself and sold several of them to his neighbors. His invention was initially welcomed by other hand spinners until they saw a fall in the price of yarn.

Opposition to the machine forced Hargreaves to leave for Nottingham, where the cotton hosiery industry benefited from the increased availability of suitable yarn. In Nottingham, Hargreaves made jennies for a man named Shipley, and on 12 June 1770, he was granted a patent, which provided the basis for legal action (later withdrawn) against the Lancashire manufacturers who had begun using it. With a partner, Thomas James, Hargreaves ran a small mill in Hockley until his death in 1778. His wife received a payment of £400.When Samuel Crompton invented the spinning mule in c.1779, he stated he had learned to spin in 1769 on a jenny that Hargreaves had built

ジェームズ・ハーグリーブス(1720年頃 – 1778年4月22日)は、イングランド・ランカシャー州で生まれ、そこで生涯を過ごした織工、大工、発明家です。彼は、紡績機械の機械化に貢献した3人の1人です。ハーグリーブスは1764年にJenny(ジェニー)紡績機を発明したことで知られています。リチャード・アークライトは1769年に水車紡績機を発明し、サミュエル・クロンプトンは2つを組み合わせて1779年にミュール紡績機を作成しました。

ジェニー紡績機は、1本の糸を紡ぐスピニングホイールが床に転がったとき、ハーグリーブスがホイールも紡錘も回転し続けているのを見て思いついたと言われています。彼は、複数の紡錘を直立させて並べれば、一度に複数の糸を紡ぐことができることに気づきました。ジェニー紡績機は、綿の経糸のみを生産することができ、十分な品質の経糸を生産することはできませんでした。後にアークライトの水車紡績機によって高品質の経糸が供給されました。

ハーグリーブスは自分でジェニー紡績機を作り、近所に数台を売りました。彼の発明は当初、他の手紡ぎ職人から歓迎されましたが、糸の価格が下落すると彼らの意見は反対に転じました。機械への反対は、ハーグリーブスがノッティンガムに移住することを余儀なくさせました。そこでは、綿の編物産業は適切な糸の増加した供給から恩恵を受けました。ノッティンガムで、ハーグリーブスはShipleyという男のためにジェニー紡績機を作り、1770年6月12日に特許を取得しました。これは、ランカシャーのメーカーに対して(後に撤回された)法的措置の根拠となりました。ハーグリーブスは、トーマス・ジェームズと共同で、1778年に亡くなるまで、ホックリーで小さな工場を経営していました。彼の妻は400ポンドの支払いを受けました。サミュエル・クロンプトンが1779年頃にミュール紡績機を発明したとき、彼は1769年にハーグリーブスが作ったジェニーで紡績を学んだと述べました。

1769 RICHARD ARKWRIGHT / THE SPINNING FRAME

Sir Richard Arkwright was an English inventor and prominent entrepreneur during the early Industrial Revolution. He played a pivotal role in the development of the spinning frame, also known as the water frame when adapted to use water power. He also patented a rotary carding engine, which transformed raw cotton into a continuous strand before spinning. Arkwright was the first to establish factories that combined mechanized carding and spinning operations. Arkwright’s major accomplishment was the successful integration of power, machinery, semi-skilled labor, and cotton as a raw material, leading to the mass production of yarn. He earned the title “father of the modern industrial factory system” for his organizational skills, which were notably demonstrated in his mill at Cromford, Derbyshire, now preserved as part of the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site.

Richard Arkwright was born in Preston, Lancashire, England, as the youngest of seven surviving children to Thomas, a tailor and Preston Guild burgess, and Sarah. Due to financial constraints, he couldn’t attend school and was taught to read and write by his cousin Ellen. Arkwright began his working life as a barber and wig-maker, later inventing a waterproof dye for fashionable periwigs that funded his early cotton machinery prototypes. In 1755, Arkwright married his first wife, Patience Holt, and had a son named Richard Arkwright Junior. Tragically, Patience died in 1756, and in 1761, Arkwright, then 29 years old, married Margaret Biggins, with whom he had three children, only Susannah surviving to adulthood. After the death of his first wife, Arkwright became interested in developing machinery for carding and spinning to replace manual labor in cotton thread production. In 1768, Arkwright, along with clockmaker John Kay, worked on a spinning machine in Preston. In 1769, he patented the spinning frame, a revolutionary machine that used wooden and metal cylinders instead of human fingers to produce twisted threads, reducing the cost of cotton-spinning significantly and revolutionizing the textile industry.

Arkwright also made improvements to Lewis Paul’s carding machine in 1775, obtaining a patent for a new carding engine that produced thin and robust cotton thread suitable for warp threads of cloth. His mills were some of the most productive in the world, and he became a wealthy man. Arkwright faced opposition from competitors and emulators seeking to challenge his patent. In 1775, he obtained a “grand patent” to strengthen his position, but public opinion was against exclusive patents, and legal proceedings dragged on until 1785, resulting in a settlement against him. At Cromford, Arkwright implemented disciplined working arrangements, organizing work in two 13-hour shifts per day and employing entire families, including children as young as seven. He encouraged weavers with large families to move to Cromford, even offering a week’s holiday on the condition that they stayed in town. After establishing the mill at Cromford, Arkwright expanded his business to Chorley and Wirksworth, where he installed the first steam engine in a cotton mill. He also contributed to establishing cotton mills in Scotland. Unfortunately, one of his mills in Lancashire was destroyed during anti-machinery riots in 1779. Arkwright died in 1792 at the age of 59. He is considered one of the most important figures in the Industrial Revolution, and his inventions helped to revolutionize the textile industry and make cotton clothing more affordable for people around the world

リチャード・アークライトは、初期の産業革命の時代に活躍したイギリスの発明家で実業家です。彼は、水力で動かす場合、水車紡績機とも呼ばれる紡績フレームの開発に重要な役割を果たしました。また、紡績前に原綿を連続した長さに変換するロータリーカードングエンジンを特許出願しました。アークライトは、機械化されたカードングと紡績を組み合わせた工場を最初に設立しました。アークライトの最大の功績は、動力、機械、半熟練労働、原材料としての綿を成功裏に統合し、糸の大量生産を実現したことです。彼は、ダーウェントバレーミルズ世界遺産の一部として保存されているダービーシャー州クロフォードの工場で顕著に示された彼の組織的スキルにより、「近代的な工業用工場システムの父」の称号を獲得しました。リチャード・アークライトは、イングランド、ランカシャー州プレストンで、7人の存命の子供のうち最年少として、仕立て屋でプレストンギルドの市民であるトーマスとサラの間に生まれました。経済的制約のために、彼は学校に通えず、いとこのエレンに読み書きを教えられました。アークライトは、理髪師とかつら職人として働き始め、後に流行のかつらのための防水染料を発明し、彼の初期の綿織物機械のプロトタイプを資金提供しました。

1755年、アークライトは最初の妻のパティエンス・ホルトと結婚し、息子のRichard Arkwright Juniorをもうけました。悲しいことに、パティエンスは1756年に亡くなり、1761年にアークライトは29歳でマーガレット・ビギンズと結婚し、3人の子供がいましたが、サラナのみが成人しました。最初の妻の死後、アークライトは綿糸生産における手作業を置き換えるために、カードングと紡績のための機械を開発することに興味を持つようになりました。

1768年、アークライトはクロフォードで時計職人のジョン・ケイ(前述のジョン・ケイとは違う)と共に紡績機械を開発しました。1769年、彼は紡績フレームを特許出願しました。これは、人間の指ではなく木製と金属のシリンダーを使用してねじれた糸を生成した画期的な機械で、綿紡績のコストが大幅に削減され、繊維産業に革命をもたらしました。アークライトはまた、1775年にルイス・ポールのカーディングマシンを改良し、新しいカーディングマソンの特許を取得しました。このカーディングエンジンは、布の縦糸に適した薄くて丈夫な綿糸を生産しました。彼の工場は世界で最も生産的なものの一つであり彼は裕福な男になりました。アークライトは、特許を争う競争相手や模倣者から反対に直面しました。1775年、彼は立場を強化するために「グランド特許」を取得しましたが、世論は独占特許に反対し、訴訟は1785年まで続き、彼に不利な和解となりました。クロフォードで、アークライトは規律の取れた就業形態を導入し、1日2回13時間のシフトで就業し、7歳までの子供も含めて家族全員を雇用しました。彼は、多くの子供を持つ織工にクロフォードに移住するよう奨励し、町に留まることを条件に1週間の休暇を提供するまでしました。クロフォードの工場を設立した後、アークライトはビジネスをチョーリーとウィークスワースに拡大し、そこで最初に蒸気エンジンを綿工場に設置しました。彼はまた、スコットランドに綿工場を設置することに貢献しました。残念ながら、彼のランカシャーの工場の1つは、1779年の反機械化暴動で破壊されました。アークライトは1792年、59歳で亡くなりました。彼は産業革命の最も重要な人物の1人と考えられています。彼の発明は、繊維産業に革命をもたらし、世界中の人々が綿の衣服をより手頃な価格で購入できるようにしました。

1776 JAMES WATT / WATT STEAM ENGINE

James Watt FRS, FRSE (30 January 1736 – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist renowned for his significant contributions to the Industrial Revolution. Building upon Thomas Newcomen’s steam engine, Watt revolutionized steam power by inventing the Watt steam engine in 1776, which had a profound impact on Great Britain and the world. While working as an instrument maker at the University of Glasgow, Watt became fascinated with steam engine technology. He identified a major inefficiency in contemporary engine designs, where a substantial amount of energy was wasted through repeated cooling and reheating of the cylinder. In order to address this issue, Watt introduced a groundbreaking improvement known as the separate condenser. This innovation eliminated energy waste and dramatically enhanced the power, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of steam engines. Furthermore, he adapted his engine to generate rotary motion, expanding its applications far beyond just pumping water.

Initially facing financial struggles while attempting to commercialize his invention, Watt found success when he partnered with Matthew Boulton in 1775. Their joint venture, Boulton and Watt, thrived, making Watt a wealthy individual. Even in his retirement, he continued inventing, although none of his later inventions matched the significance of his groundbreaking work on the steam engine. Watt’s contributions to engineering were so profound that he even developed the concept of horsepower, which eventually led to the naming of the SI unit of power, the watt, in his honor.

The Watt steam engine was a significant improvement over previous steam engines, as it was much more efficient and powerful. This made it possible to use steam engines for a wider variety of applications, such as powering factories and mills. The Watt steam engine played a major role in the Industrial Revolution, and it helped to transform the way goods were produced and distributed. The separate condenser was one of the most important innovations in the history of steam power. It allowed steam engines to be much more efficient, which in turn made them more powerful and cost-effective. This led to a wide range of new applications for steam engines, which helped to drive the Industrial Revolution.

ジェームズ・ワット(1736年1月30日 – 1819年8月25日)は、スコットランドの発明家、機械工学者、化学者であり、産業革命への多大な貢献で有名です。トーマス・ニューコメンの蒸気機関を基盤として、1776年にワット蒸気機関を発明し、蒸気動力を革命的に変え、イギリスと世界に大きな影響を与えました。グラスゴー大学の機械製作者として働いていたとき、ワットは蒸気機関技術に魅了されました。彼は、当時のエンジン設計に大きな非効率性があることを特定しました。これは、シリンダーを繰り返し冷却して再加熱することにより、大量のエネルギーが浪費されていました。この問題に対処するために、ワットは別個の冷却器と呼ばれる画期的な改良を導入しました。この革新はエネルギーの浪費を排除し、蒸気機関のパワー、効率、コスト効率を劇的に向上させました。さらに、彼はエンジンを改造して回転運動を生成するようにし、その用途を水を汲み上げるだけに拡大しました。

当初、彼の発明を商業化する際に財政的困難に直面していましたが、1775年にMatthew Boultonと提携したときに成功を収めます。彼らの合弁会社、ボウルトン・アンド・ワットは繁栄し、ワットは裕福になりました。引退後も発明を続けましたが、彼の後のどの発明も蒸気機関に関する彼の画期的な仕事の重要性に匹敵しませんでした。ワットのエンジニアリングへの貢献は非常に重要で、彼は馬力という概念を開発し、最終的には彼に敬意を表して馬力=ワットの名前が付けられました。ワット蒸気機関は、以前の蒸気機関よりも大幅に改良され、はるかに効率的で強力でした。これにより、蒸気機関を工場や工場を動力源とするなど、より広い範囲の用途に使用できるようになりました。ワット蒸気機関は産業革命において重要な役割を果たし、商品の生産と流通の方法を変えるのに役立ちました。別個の冷却器は、蒸気動力の歴史の中で最も重要な革新の1つです。それは蒸気機関をはるかに効率的にし、それは彼らをより強力で費用対効果の高いものにしました。これは、蒸気機関の新しい用途の広い範囲につながり産業革命を推進しました。

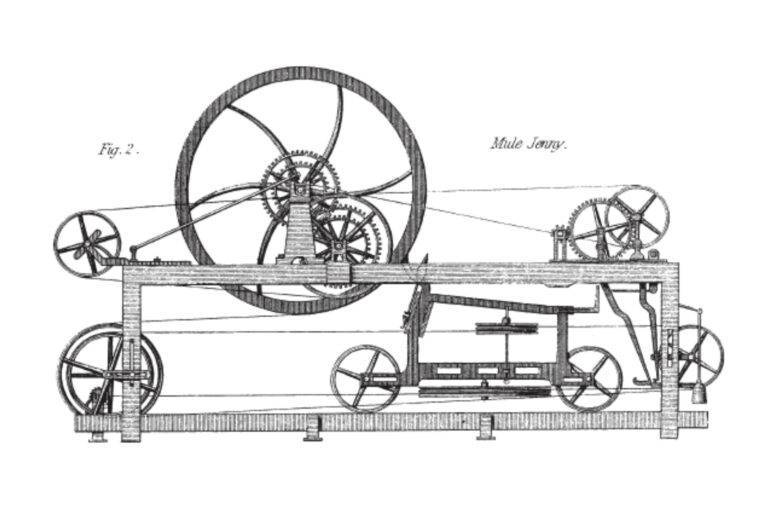

1779 SAMUEL CROMPTON / THE SPINNING MULE

In 1779, Samuel Crompton invented a new machine, the mule spinning machine, also called the jenny mule. The machine was named after the fact that it is a cross between two machines: the spinning jenny and the water frame.The machine has a two-wheeled component called the carriage in the center of the lower part. The carriage is installed with a spindle, which is used to wind the thread. The carriage moves along the rails, stretching the coarse yarn and twisting it at the same time. This process is called plying. As the yarn is twisted while being stretched, the cross-section of the yarn takes on a rounded shape. When the carriage reaches the end of the rail, it returns to its original position while the twisted yarn is wound onto the spindle.The machine was made of wood and was powered manually in the early stages. This is why it is also called a manual mule spinning machine. It required the skill of an experienced person to coordinate the internal running process. One person could only operate 264-288 weights at the same time.

He humbly stated that this invention was merely an improvement on others’ inventions, and published it without obtaining a patent in 1780, dying without applying for one until the end of his life.

1779年に、サミュエル・クロンプトンは新しい機械、ミュール紡績機(ジェニーミュールとも呼ばれます)を発明しました。この機械は、スピニング・ジェニーとウォーターフレームの両方の機械を組み合わせたものです。機械の下部中央には、車輪が2つ付いた部品がありその名は「キャリッジ」と言います。キャリッジには、糸を巻き取るための紡錘が取り付けられています。キャリッジはレール上を移動し粗い糸を伸ばしながら同時に撚りをかけます。このプロセスは「撚糸(糸を2本以上撚り合わせてより強度のある糸に加工する方法)」と呼ばれます。糸が伸ばされながら撚りをかけられるため、糸の断面は丸い形になります。キャリッジがレールの端に到達すると、撚りをかけられた糸が紡錘に巻き取られながら、元の位置に戻ります。この機械は木で作られており、初期は手動で動かされていました。そのため、手動ミュール紡績機とも呼ばれています。内部の動作を調整するには熟練した技術が必要でした。1人の操作者は、264〜288の錘を同時に操作することができました。

彼は、この発明は他人の発明を改良したものに過ぎないと謙虚し1780年に特許を取得することなく発表、最後まで特許を申請することなく生涯を終えました。

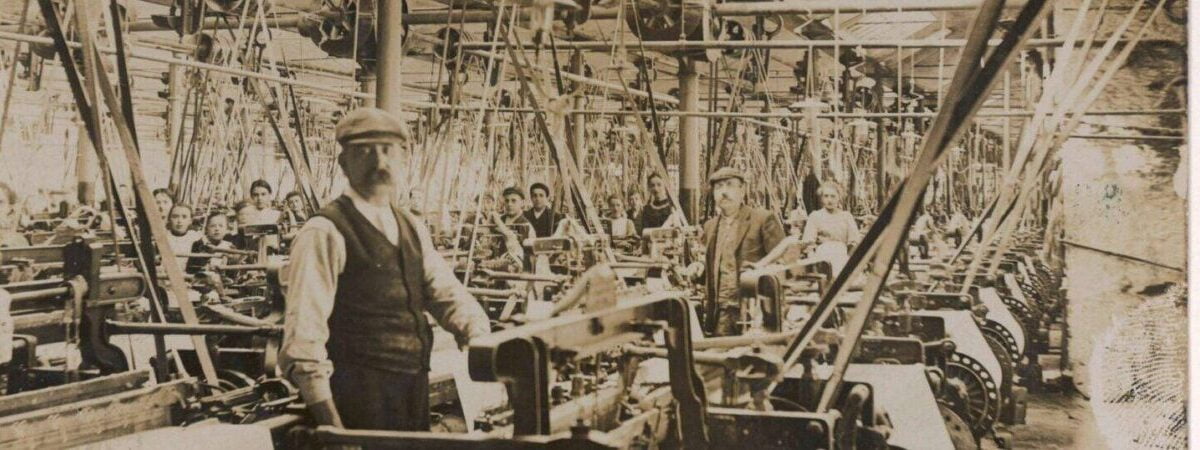

Lancashire cotton

The demand for cotton grew as the population of Britain and its empire expanded. Cotton mills, also known as spinning mills, became a common sight in north-west England. In Manchester alone, the number of cotton mills increased from two in 1790 to 66 in 1821. The textile industry was the dominant industry in Tameside, east Manchester, from the late 18th century to the mid-20th century. The cotton textile trade, dominated by cotton spinning, led to the construction of hundreds of factories in the area. This in turn led to the growth of the metropolitan population of the towns of Ashton, Duckinfield, Hyde, Mossley, and Stalybridge.

Cotton textiles had several advantages over woollen fabrics. They were cheaper, could be printed with brightly coloured patterns and text, and were easier to wash. This made them more hygienic, which is thought to have led to an increase in life expectancy. The widespread use of cotton textiles also destroyed rural cottage industries in India, as British industrial cotton textiles were cheaper and more efficient. As a result, cotton textile production areas such as Dhaka (now Bangladesh) declined rapidly. The East India Company began to import Indian cotton as raw material instead.

綿の需要は大永帝国の人口が拡大するにつれて増加しました。綿紡績工場としても知られる綿工場は、北西イングランドで一般的な産業形態になりました。マンチェスターだけでも、綿工場の数は1790年の2から1821年の66に増加しました。18世紀後半から20世紀半ばまで、テムズサイド(マンチェスター東部)の繊維産業は、綿紡績を主とした綿織物貿易が盛んで、数百の工場が建てられました。これは、アシュトン、ダッキンフィールド、ハイド、モズレー、スタリブリッジなどの町の都心部人口の増加につながりました。 綿織物は、ウール織物よりいくつかの利点がありました。安価で、明るい色の模様や文字を印刷することができ、洗濯が容易でした。これにより衛生的になり寿命の延長につながったと考えられています。綿織物の広範な使用は、イギリスの工業用綿織物が安価で効率的であったため、インドの農村の家庭産業を破壊しました。その結果、ダッカ(現在はバングラデシュ)などの綿織物生産地は急速に衰退しました。東インド会社は、代わりにインド綿を原料として輸入するようになりました。

1819 THE PETERLOO MASSACRE

The Peterloo Massacre took place on Monday, 16 August 1819, at St Peter’s Field in Manchester, Lancashire, England. The incident resulted in the deaths of 18 people and injuries to 400 to 700 others. The cavalry charged into a crowd of approximately 60,000 people who had assembled to demand parliamentary representation reform. The aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 had brought about an economic downturn, accompanied by widespread unemployment and crop failures due to the Year Without a Summer. The Corn Laws, which kept bread prices high, exacerbated the situation. At that time, only about 11% of adult males had the right to vote, with very few from the industrial north of England, which was severely affected. Reformers saw parliamentary reform as the solution and launched a massive campaign to petition for manhood suffrage, amassing three-quarters of a million signatures in 1817. However, their plea was firmly rejected by the House of Commons. In early 1819, as another slump hit, radical reformers sought to mobilize large crowds to pressure the government into action. The movement gained strength, particularly in the north-west, where the Manchester Patriotic Union organized a massive rally in August 1819, addressed by the renowned radical orator Henry Hunt.

At the start of the meeting, local magistrates called on the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry to arrest Hunt and others on the platform. The Yeomanry charged into the crowd, resulting in the death of a child and injuries to many, eventually apprehending Hunt. Following this, the chairman of Cheshire Magistrates summoned the 15th Hussars to disperse the crowd. With sabres drawn, the Hussars charged, leading to the death of between 9 and 17 people and injuries to 400 to 700 others. The Manchester Observer newspaper was the first to coin the term “Peterloo massacre” in a bitterly ironic reference to the bloody Battle of Waterloo that occurred four years earlier.

ピータールーの虐殺は、1819年8月16日月曜日、イングランド、ランカシャーのマンチェスターにあるセントピーターズフィールドで起こりました。この事件は、議会改革を要求するために集まった約60,000人の群衆に騎兵が突入した結果、18人が死亡し、400〜700人が負傷しました。1815年のナポレオン戦争の余波は、不作の年による失業と作物の失敗に伴う経済不況をもたらしました。高価なパンの価格を維持する穀物法は、事態を悪化させました。当時、成人男性の約11%だけが投票権を持っており、工業化された北イングランドからはほとんどありませんでした。改革派は議会改革を解決策と見て、1817年に375万の署名を集めた男子参政権を求める大規模なキャンペーンを開始しました。しかし、彼らの請願は下院によって断固として拒否されました。1819年初頭、別の不況が襲ったため、急進的な改革派は政府に行動を起こすよう圧力をかけるために大規模な群衆を動員しようとしました。この運動は、特に北西部で勢力を増し、1819年8月にマンチェスター愛国同盟が著名な急進的演説家ヘンリー・ハントを迎えて大規模な集会を開催しました。会議の開始時に、地元の治安判事はマンチェスターとサルフォード・ヨマンリーにプラットフォーム上のハントらを逮捕するよう命じました。ヨマンリーは群衆に突入し、子供1人の死亡と多くの負傷を引き起こし、最終的にハントを取り押さえました。その後、チェシャー治安判事の議長は、群衆を解散させるために第15連隊を召喚しました。サーベルを抜いて、ハッサーは突撃し、9〜17人の死亡と400〜700人の負傷につながりました。マンチェスター・オブザーバー紙は、この事件を4年前に起こった血なまぐさいワーテルローの戦争に皮肉な言及で「ピータールーの虐殺」と最初に名付けました。

– recommendation –

"FUSTIAN" THE STARTING THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Do you know the name of the fabric “fustian”? It is not a well-known name today, but it is actually a very important material for the Industrial Revolution, as well as for its long history. The term “fustian” varies from period to period, as there are several combinations of materials used in different periods. In this issue, we will study the relationship between “fustian” and the Industrial Revolution.