What is the flannel ?

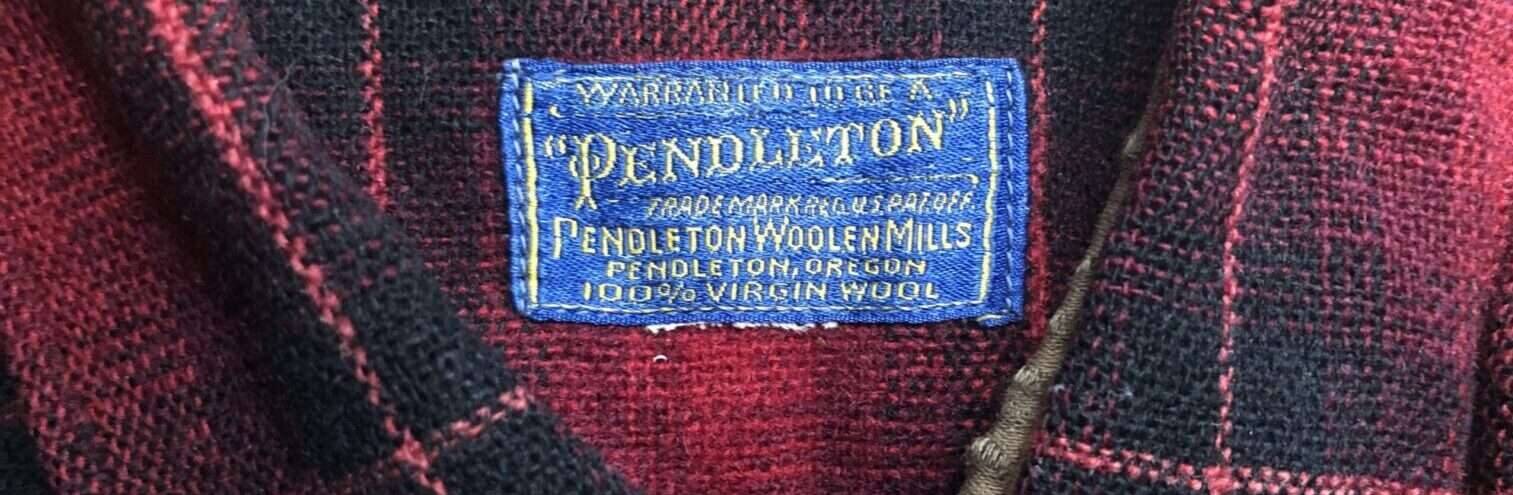

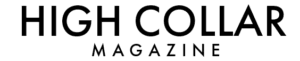

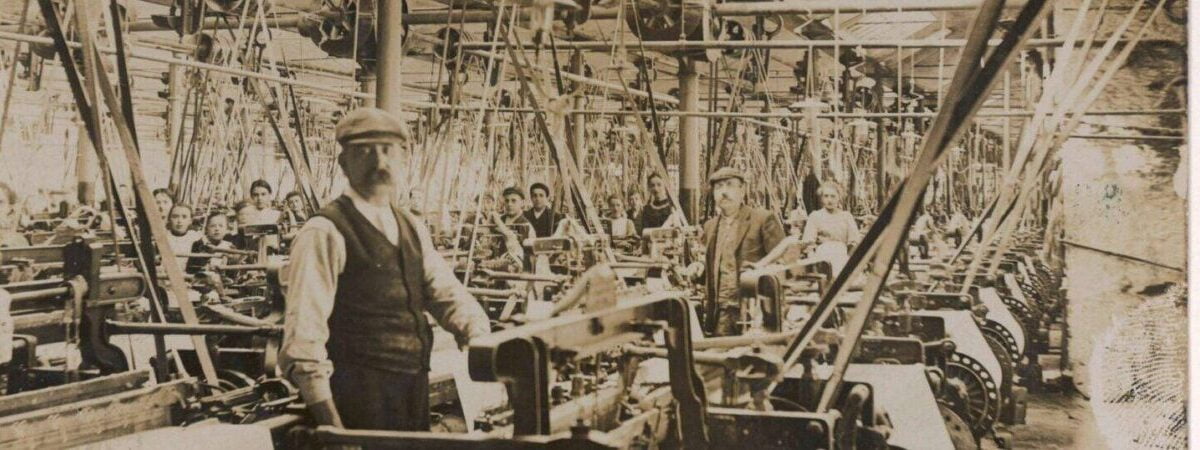

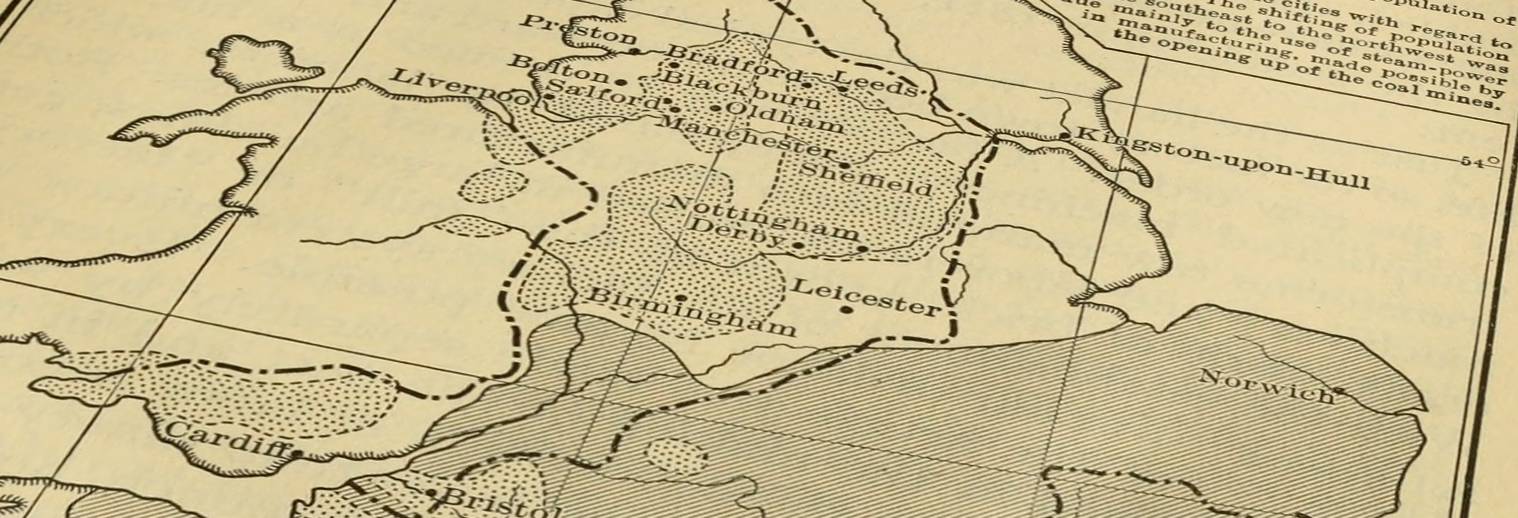

While mechanized flannel produced by steam-powered mills became more common, hand-loom woven flannel remained highly valued due to its superior quality. Pryce Jones leveraged the term “Welsh flannel” to signify excellence in his garments. A downturn in trade during the 1830s can be attributed to both the decline of the trans-Atlantic slave cloth market and the loss of the Drapers Guild’s monopoly status in Shrewsbury. To address this gap, Newtown’s Flannel Market was erected in 1832. The first successful mechanical mill in Newtown began operations in 1853, although hand-loom production persisted until the early 20th century. Even as late as 1891, census data indicated twice as many flannel weavers as woolen weavers in the Penygloddfa area of Newtown. Nevertheless, competition from regions like Lancashire and Yorkshire led to the decline of the trade. Recent research has shed light on the role of this fabric in the slave trade, with each slave being allocated five yards of flannel annually. Originally produced on farms to supplement agricultural income, flannel production underwent industrialization and centralization in 19th century mid-Wales. Initially, water-powered fulling and carding mills were utilized, followed by the adoption of steam-powered mills.

▪️ The raising finishing process can be used to create a variety of different textures on fabrics, from a soft and fuzzy nap to a more pronounced and durable pile.

▪️ The raising rollers are typically made from a hard rubber or metal, and the needles are made from a high-carbon steel.

▪️ The raising finishing process can be used on both woven and knitted fabrics, but it is most commonly used on wool and cotton fabrics.

▪️ Raising finishing can be a relatively expensive process, but it can add significant value to fabrics by improving their appearance, feel, and performance.

起毛加工は生地の表と裏の両方に毛のような質感を与えることができ、その結果、外観が幾重にも変化し、よりソフトで充実した手触りになり、かさも増す。この起毛加工は生地の環境要素に対する回復力に貢献し、起毛内のエアセルによって断熱性と保温性を高める。モコモコとした表面を作るには、先端が鉤状になった金属針を使って糸から繊維端を引き抜く必要があり、この針は生地の表面を優しく擦るローラーに埋め込まれている。

ローラーから突き出た針には45°のフックがついており、このフックは太さと長さが異なり、起毛ローラーに螺旋状に巻かれた専用のゴムベルトの中に配置されている。これらのローラーは通常、布の送り方向にフックが向けられたパイルローラーと、フックが反対方向に向けられたカウンターパイルローラーに交換されます。

▪️ 起毛仕上げ工程は、ソフトでファジーな起毛から、より顕著で耐久性のあるパイルまで、生地にさまざまな風合いを出すために使用できる。

▪️ 起毛ローラーは通常、硬質ゴムまたは金属から作られ、針は高炭素鋼から作られる。

▪️ 起毛仕上げ加工は織物とニット生地の両方に使用できますが、最も一般的に使用されるのはウールとコットンの生地です。

▪️ 起毛加工は比較的高価な加工ですが、外観、手触り、性能を向上させることで生地に大きな付加価値を与えることができます。

In 1618, the first brick house in Shrewsbury was constructed by William Rowley, a brewer and draper. By 1638, the inaugural mayor of Shrewsbury, Thomas Jones, held a prominent position as a leading draper.

In 1621, Sir Edward Coke sponsored the Welsh cloth bill, which aimed to break the Company’s effective monopoly over cloth transportation to London. Initially, the bill proposed that all merchants should have the freedom to purchase cloth anywhere in Wales and export it upon payment of duties to the crown. The export provision was later qualified to stipulate that exportation could only occur after the cloth had been fully processed domestically. Opposition to the bill arose from two Shrewsbury burgesses during its third reading in 1621, arguing that it would undermine standards for Welsh cloth dimensions, facilitate practices like forestalling and ingrossing, challenge Shrewsbury’s charter, and permit Welsh clothiers to vend their products in any English town. Coke countered these contentions, asserting that Shrewsbury would only suffer due to its monopoly and that monopolies should be condemned as they could not be justified on grounds of state reason. The bill was subsequently passed by the commons and forwarded to the Lords.

In 1621, the drapers collectively “agreed to buy no more cloth in Oswestry.” Notably, John Davies noted in 1633 that the market for Welsh cottons had brought prosperity to Oswestry, but this shifted to Shrewsbury after the staple of cloth was transferred there, leading to Oswestry’s decline. After the market relocated to Shrewsbury, a clothier from Merioneth had to travel a greater distance, resulting in delays. Responding to a plea in 1648, the drapers compromised by deciding to purchase cloth on Thursdays.

After the English Civil War (1642–51), regulations were instituted in 1654 “to prevent the Drapers from forestalling or engrossing Welsh flannels, cloths, etc.” Many of the drapers had aligned themselves with Parliament during the civil war, leading to a lack of royal support for the Company after the monarchy was reinstated in 1660 under Charles II (1660–85). Subsequently, the cloth trade experienced a gradual decline, with the number of drapers dwindling to 61 by 1665.

1848年と1853年、サミュエル・ハリスはエイバノニ・イースタードフォダウで羊毛製品で数々の賞を受賞しました。

1865年、サミュエル・フランクリン・ハリスは、ランオーバー卿の水車小屋の賃貸契約に名を連ねました。

1884年、グウェンフリッド毛織物工場のスケッチ。

1889年8月9日、サミュエル・フランクリン・ハリスは73歳で亡くなりました。子供たちはしばらくの間続けました。

1891年、フランクリン・ジェームズ・ハリス(サミュエルの息子)は世帯主でした。彼はメアリー・ジェレミアと結婚し、織りを辞めました。

1892年、ジョン・ジョーンズはクリスマスから工場を引き継ぎました。

1894年、工場は修理されました(工場の銘文「Gwenffrwd 1839 Adgyweiriwyd [修理] 1894」)。

1950年、工場での生産が停止しました

Ty’r Eglwys, Llanover,

Abergavenny.

April 24th, 1909.

Dear Mr. Thomas,

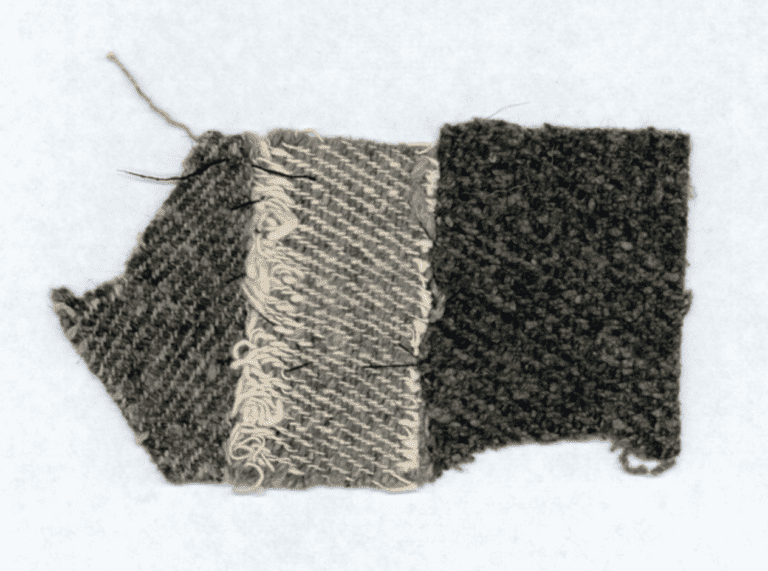

I am sending you a small section of Welsh flannel, as you had previously expressed interest in having one. This particular piece features the Gwenffrwd pattern, often referred to by the late Lady Llanover. Are you referring to the same design that you mentioned as the ‘Chartist’? I did come across a pattern by that name at the Welsh Industries Depot in Cardiff, but I am uncertain if they are indeed identical.

Best regards,

S.B. Gruffydd-Richards (National Museum of Wales)

タイ’ル・エグルウィス、ランノヴァー、アバーガヴェニ。

1909年4月24日。

親愛なるトーマス氏、

以前にサンプルがほしいとおっしゃっていたウェルシュフランネルの小片をお送りしています。この特定の部分には、故レディ・ランノヴァーが「グウェンフルード」パターンと呼んでいたデザインが施されています。おっしゃる「チャーティスト」とは同じデザインを指しているのでしょうか?カーディフのウェルシュインダストリーズデポでその名前のパターンを見かけましたが、それが本当に同一であるかどうか確信が持てません。

よろしくお願い申し上げます。

S.B. グリフィス・リチャーズ (ウェールズ国立博物館)

"FUSTIAN" THE STARTING THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

ABOUT THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION