RUFF

DECORAQTIVE COLLARS

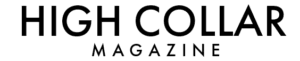

This impressive portrait, painted about 1618 when the artist was eighteen or nineteen years old, is very close in style to contemporary and slightly earlier portraits by Rubens, for whom Van Dyck was working at the time. In its insistence on volume and textures, the close attention to costume detail, and the passive pose and expression, the painting also adheres to an older Netherlandish tradition, as seen in portraits by Anthonis Mor (ca. 1516/19-ca. 1575/76).

Elizabeth I, also known as the “Virgin Queen,” was one of the most famous monarchs in English history. She was born on September 7, 1533, in Greenwich Palace, London. Her birth was a significant event because it marked the beginning of a new era for England. Her father, King Henry VIII, had sought to annul his marriage to Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn, in order to marry someone else and produce a male heir. When the Pope refused to annul the marriage, Henry broke away from the Roman Catholic Church, leading to the English Reformation. Elizabeth’s early life was marked by turmoil and uncertainty. Her mother, Anne Boleyn, was executed on charges of adultery and treason when Elizabeth was just three years old. After her mother’s death, Elizabeth’s status in the royal court became precarious. She was declared illegitimate, and her half-sister Mary I succeeded to the throne.

Despite the challenges she faced, Elizabeth received a well-rounded education, which included subjects such as history, languages, music, and theology. Her education proved invaluable when she eventually ascended to the throne. In 1558, after the death of her sister Mary, Elizabeth became Queen of England at the age of 25. Her reign marked a pivotal period in English history. Elizabeth was a skilled diplomat and a master of statecraft. She navigated the complex political landscape of Europe, which was fraught with religious tensions between Catholics and Protestants.

One of the most significant achievements of Elizabeth’s reign was the establishment of the Church of England, separate from the authority of the Pope in Rome. She passed the Act of Supremacy in 1559, making her the Supreme Governor of the Church of England. This move solidified the Protestant Reformation in England and set the stage for the religious landscape of the country for centuries to come. Elizabeth’s reign is often referred to as the “Elizabethan Era” or the “Golden Age.” During this period, England experienced a flourishing of arts, literature, and exploration. Some of the greatest literary figures in history, including William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe, produced their masterpieces during her rule. The era also witnessed explorers like Sir Francis Drake circumnavigating the globe and the founding of the first English colony in America, at Roanoke Island.

One of the most defining moments of Elizabeth’s reign was the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. The powerful Spanish fleet, sent by King Philip II of Spain, was defeated by the English navy under the command of Sir Francis Drake. This victory secured England’s position as a major naval power and marked a turning point in European history. Throughout her reign, Elizabeth maintained a carefully cultivated image of the “Virgin Queen.” She never married, despite numerous suitors and political pressures to secure an heir to the throne. Her decision to remain unmarried allowed her to maintain her independence and focus on her role as a ruler. Elizabeth I’s reign lasted for 45 years, from 1558 to 1603. She passed away on March 24, 1603, at the age of 69, marking the end of the Tudor dynasty. Her successor was James VI of Scotland, who became James I of England, uniting the crowns of England and Scotland. Elizabeth’s legacy is enduring, and she is remembered as one of the most iconic and influential monarchs in English history. Her reign is celebrated for its cultural achievements, political stability, and England’s emergence as a global power during the Elizabethan Era.

The technique of cutwork used to make this piece of lace was the creation of a delicate structure of needle lace stitches across the spaces cut in a fine linen ground. It reached the height of its popularity in the late sixteenth and early seventeeth century, when it was used to decorate every type of linen and in particuar to draw attention to the face and throat in the form of collars and ruffs. This short length of border may well have been part of a ruff, and it has been reconstructed in this way in the museum with the attachment of a linen support.