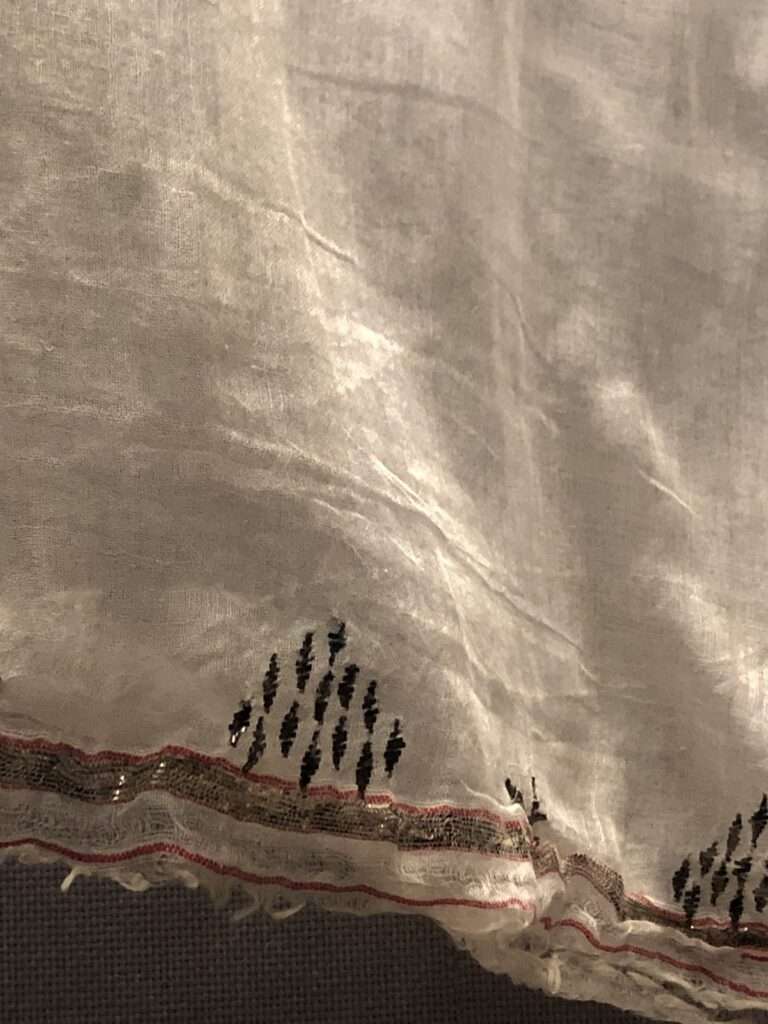

Marie Antoinette, who was the last queen of France before the French Revolution, is often associated with muslin, a lightweight cotton fabric. Muslin was a popular fabric in France during the 18th century, and Marie Antoinette was known to be a big fan of the fabric.

Marie Antoinette’s fondness for muslin was partly due to her interest in fashion and her desire to be seen as a trendsetter. She was known for wearing muslin dresses and using muslin as a decorative element in her clothing and interior design.

Muslin also played a role in the political and social tensions leading up to the French Revolution. As the popularity of muslin increased, so did its production and importation, leading to concerns about the impact on the French textile industry. There were also concerns about the extravagance and excess associated with muslin and the fashion trends it represented, which were seen as emblematic of the decadence and disconnection of the French aristocracy. In short, while Marie Antoinette’s personal relationship with muslin was one of fashion and style, the fabric also had a broader cultural and political significance in 18th century France.

Marie Antoinette in a Muslin dress (Marie Antoinette in einem Musselinkleid) Elisabeth Louise after Vigee Lebrun 1783

There is no definitive answer to why Marie Antoinette liked muslin, but there are several factors that may have contributed to her fondness for the fabric.

First, muslin was a lightweight and breathable fabric that was well-suited for warm weather. As a member of the French court, Marie Antoinette would have been expected to wear clothing appropriate for the season and climate, and muslin would have been a practical choice for summer attire.

Second, muslin was a fashionable fabric in the late 18th century, and Marie Antoinette was known for her interest in fashion and her desire to be seen as a trendsetter. By wearing muslin dresses and using muslin as a decorative element in her clothing and interior design, she may have been trying to set new fashion trends and demonstrate her status as a style icon.

Finally, Marie Antoinette was a patron of the arts and was known for her support of artists and craftsmen. Muslin was a fabric that could be embellished with embroidery, lace, and other decorative elements, making it a popular choice for artists and artisans who wanted to showcase their skills. By promoting the use of muslin, Marie Antoinette may have been supporting the French textile industry and encouraging the production of high-quality fabrics and embellishments.

Elisabeth Louise Vigee Lebrun

Madame Le Brun, born Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun on April 16, 1755, was a prominent French portrait painter in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with a focus on women. Her artistic style reflected elements of the Rococo and Neoclassical movements, blending a Rococo color palette with a Neoclassical approach. She gained notoriety as the portrait painter for Marie Antoinette and earned patronage from European aristocrats, actors, and writers. She was elected to art academies in ten cities and was admired by contemporary artists like Joshua Reynolds, who considered her one of the greatest portraitists of her time, comparable to the old Dutch masters. Vigée Le Brun created over 660 portraits and 200 landscapes, many of which are held in private collections and major museums worldwide, including the Louvre, the Hermitage Museum, the National Gallery in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In her personal life, Vigée Le Brun was highly sensitive to her surroundings, with heightened senses of sound, sight, and smell. In her 80s, she wrote her memoirs in three volumes, entitled “Souvenirs,” which included pen portraits and advice for aspiring portraitists.

Self-portrait with her daughter Julie, 1786

Elisabeth Louise Vigee Lebrun

Muslin is a type of cotton fabric that has a plain weave and comes in a variety of weights, ranging from delicate sheers to coarse sheeting. Its name originates from the city of Mosul, Iraq, where it was first produced. During the 17th and early 18th centuries, a particularly fine type of handwoven muslin made from delicate handspun yarn was imported to Europe from the Bengal region of South Asia. This traditional art of weaving Jamdani muslin in Bangladesh was recognized by UNESCO in 2013 and included in the list of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

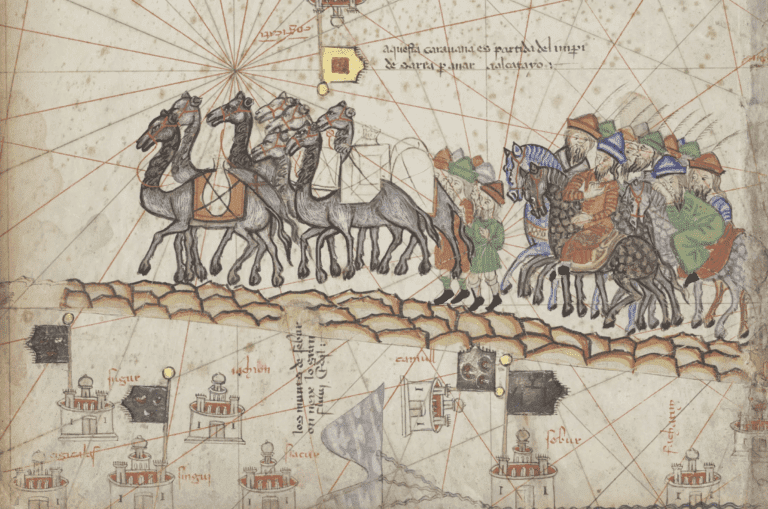

Mosul is the city in Northern Iraq where Marco Polo had documented muslin to have originated. In fact, this is just where Europeans discovered it; muslin is thought to have originated in Dhaka, which was in Bengal.

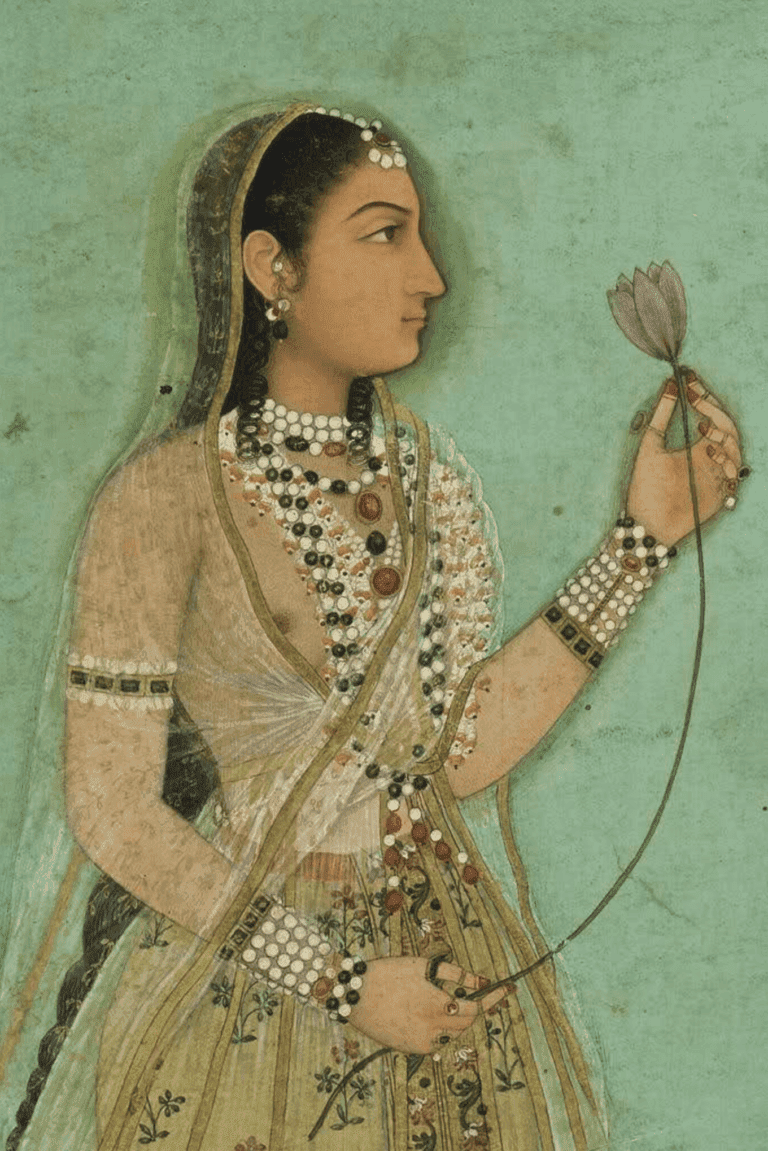

A woman in fine Bengali muslin, “Muslim Lady Reclining” by Francesco Renaldi (1789) ©wikipediacomon

c. 1600, “delicately woven cotton fabric,” from French mousseline (17c.), from Italian mussolina, from Mussolo, Italian name of Mosul, city in northern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) where muslin was made. Like many fabric names, it has changed meaning over the years, in this case from luxurious to commonplace. In 13c. French, mosulin meant “cloth of silk and gold.” The meaning “everyday cotton fabric for shirts, bedding, etc.” is first attested 1872 in American English.

Portrait of Prince Salim

Mughal, c. 1620-30

British Library, Add.Or.3854

T̤abaḳāt-i-nāsiri

a general history of the Muhammadan dynastics of Asia, including Hindustān, from A.H. 194 (810 A.D.) to A.H. 658 (1260 A.D.) and the irruption of the infidel Mughals into Islām tr. from original Persian manuscripts, by H. G. Raverty

The country of Bengal is called, by way of distinction, the paradise of the earth. It not only abounds with the necessaries of life to such a degree, as to furnish a great part of India with its superfluity, but it abounds in very curious and valuable manufactures, sufficient not only for its own use, but for the use of the whole globe. The silver of the west and the gold of the east have for many years been pouring into that country, and goods only have been sent out in return. This has added to the luxury and extravagance of Bengal.

Let us for a moment consider the nature of the education of a young man who goes to India. The advantages arising from the Company’s service are now very generally known; and the great object of every man is to get his son appointed a writer to Bengal; which is usually at the age of 16. His parents and relations represent to him how certain he is of making a fortune; that my lord such a one, and my lord such a one, acquired so much money in such a time; and Mr. such a one, and Mr. such a one, so much in such a time. Thus are their principles corrupted at their very setting out, and as they generally go a good many together, they inflame one another’s expectations to such a degree, in the course of the voyage, that they fix upon a period for their return before their arrival. (From D. B. Horn and Mary Ransome, eds., English Historical Documents, 17141783 (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1957), pp. 809-811.)

The humid climate was crucial to the spinning process, which was typically done in the morning or evening. Young women weavers used water bowls to keep the air moist while they worked.

For centuries, the Dhaka region of present-day Bangladesh, extending from Mymensingh in the north to Barisal in the south, was renowned for producing the finest hand-woven cotton textiles in the world. Traders from various corners of the globe flocked to this region to purchase the highly coveted cotton textiles and silk that were made by ordinary people in the area. The quality and reputation of Bengal textiles were extolled by outside travelers and textile buyers, who wrote about their experiences and sometimes even embellished them with mythical descriptions. Numerous reports and writings attest to the high value placed on the textile products of Bengal villages in the past, which were eagerly sought after and enjoyed by people all over the world. The following quote from Campus serves as an example of how far back in history Bengal’s reputation extends:

“There was a time when the muslins of Dacca shipped from Satgaon clad Roman ladies and when spices and other goods of Bengal that used to find their way to Rome through Egypt were very much appreciated there and fetched fabulous prices…” (History of the Portuguese in Bengal, (J. J. A. Campos)

The Bengal region produced a wide range of textiles, including cotton, silk, and blended fabrics, which were used both locally and exported. Raw silk was also a valuable export item, accounting for up to one-fifth of the total. These textiles were given beautiful names that often reflected the aesthetic feelings inspired by nature. While there were hundreds of different types of textiles produced in Bengal, certain cotton fabrics were grouped together and known as muslin due to their shared characteristics of being made from very fine cotton threads and having a loose, somewhat transparent weave. Bengal was just one of several textile export centers in India, each with its own unique specialties, that supplied fabrics to the world. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to directly bring back textiles from India, including Bengal, starting in the early 1500s. The Dutch and the English also entered the Indian Ocean trade from the early 1600s, but their initial textile trade focused primarily on inter-Asia trade, whereby they purchased Indian textiles in exchange for Indonesian spices and other goods from Asia.

Written in the Persian language by Abu’l Fazl, the court historian of Emperor Akbar, the Ain-i-Akbari (Persian: آئینِ اکبری) or “Administration of Akbar” is a comprehensive document from the 16th century that provides detailed records of the Mughal Empire’s administration. It constitutes the third volume and final segment of the Akbarnama (Account of Akbar), another extensive work by Abu’l Fazl, and is comprised of three volumes itself.

The Akbarnama’s third volume, known as the Ain-i-Akbari, presents a compilation of administrative reports in the form of a gazetteer regarding the reign of Akbar. As explained by Blochmann, the book offers a detailed account of the emperor’s mode of governing and serves as a statistical return of his government around 1590. The Ain-i-Akbari consists of five books, each covering a different topic. The first book, manzil-Abadi, delves into the maintenance of the imperial household, while the second, sipah-abadi, focuses on the military and civil services and the emperor’s servants. The third book discusses the regulations for the judiciary and executive administration of the empire. The fourth book includes information on Hindu philosophy, science, social customs, and literature. Finally, the fifth book features Akbar’s sayings and also provides an account of the author’s ancestry and biography.

Muslin has several kinds of variations. Many of the below are mentioned in Ain-i-Akbari (16th-century detailed document)

In contemporary times, muslin is made using either cotton or poly-cotton, with the same plain weave as the original. The fabric is still woven with an open-sett construction similar to cheesecloth, allowing for both the delicacy of cotton muslin and the durability of synthetic fabrics.

The humid climate was crucial to the spinning process, which was typically done in the morning or evening. Young women weavers used water bowls to keep the air moist while they worked.

The cloth known as muslin was mentioned by Marco Polo in his book The Travels back in 1298 CE. According to Polo, it was produced in Mosul, Iraq. Later, in the 16th century, English traveler Ralph Fitch praised the quality of muslin he encountered in Sonargaon. By the 17th and 18th centuries, Mughal Bengal had become the leading exporter of muslin worldwide, with the capital city of Mughal Dhaka playing a key role in the trade. In the 18th century, muslin gained widespread popularity in France and eventually spread throughout much of the Western world.

The muslin fabrics produced in Dhaka during the 18th century were made exclusively of cotton. They were incredibly lightweight, delicate, and transparent, with excellent breathability. These fabrics often contained between 1000-1800 yarns in the warp and weighed only 3.8 ounces (110 grams) per yard for a 10-yard length (9.14 meters by 0.91 meters). Some types of muslin were so fine that they could even pass through the opening of a lady’s finger ring.

the Satyricon, Gaius Petronius Arbiter, a Roman courtier and author from the 1st century AD, described the sheer quality of muslin fabric in the following words:

“Thy bride might as well clothe herself with a garment of the wind as stand forth publicly naked under her clouds of muslin.”

Dupin, Nicolas. Graveur : Le Clerc, Pierre Thomas.) 1912

Prior to the mid-17th century, clothing, textiles, and fashion in Britain were unremarkable. However, this began to rapidly and dramatically change in the latter half of the century due to India’s influence. Gujarat was the first source of transformation, followed by Madras, and finally Bengal. The English East India Company’s voyages to Asia brought back spices, textiles, and other useful items to Britain, which helped turn the country into an increasingly exciting place. Defoe’s Everybody’s Business is Nobody’s Business provides an indication of how this change was viewed at the time, as he observed that…

plain country Joan is now turned into a fine London madam, can drink tea, take snuff, and carry herself as high as best. She must have a hoop too, as well as her mistress; and her poor scanty linsey-woolsey petticoat is changed into a good silk one, four or five yards wide as the least.

Niall Furguson stated that during the 17th century, the discerning English shopper had only one outlet to buy high-quality clothes from – India. When English merchants began importing Indian silks and calicoes, it resulted in a national transformation, impacting every aspect of British life. In 1663, Samuel Pepys took his wife Elizabeth shopping in Cornhill, a fashionable shopping district of London, and they purchased a painted Indian calico, also known as a chintz, to line her new study. Pepys himself went to the trouble of hiring a fashionable Indian silk morning gown, or banyan, when he sat for artist John Hayls. Over a quarter of a million pieces of calico were imported into England in 1664, and there was almost as much demand for Bengal silk, silk cloth taffeta, and plain white cotton muslin. Defoe recalled in the Weekly Review of 31 January 1708 that Indian fabrics had crept into British homes and were used for curtains, cushions, chairs, and even beds.

In 1607, the East India Company’s first visit to the Indian subcontinent was to Gujarat, primarily for the purpose of purchasing Indian textiles to exchange for Indonesian spices. For about 30 years, Gujarat was the primary source of Indian textiles for the Company. However, from 1640, when the Company established a base in Madras in South India, another important center was added. The third and most significant center of textile production for the Company was Bengal, where it began purchasing textiles around the 1660s. Initially, Bengal’s contribution was minimal, but it gradually increased to become the main supplier of the East India Company’s textile needs. By 1725, Bengal’s contribution to the Company’s textile exports exceeded that of the other two centers combined, a trend that continued throughout the 18th century. As a result, a significant portion of Indian textiles imported to Britain originated from Bengal.

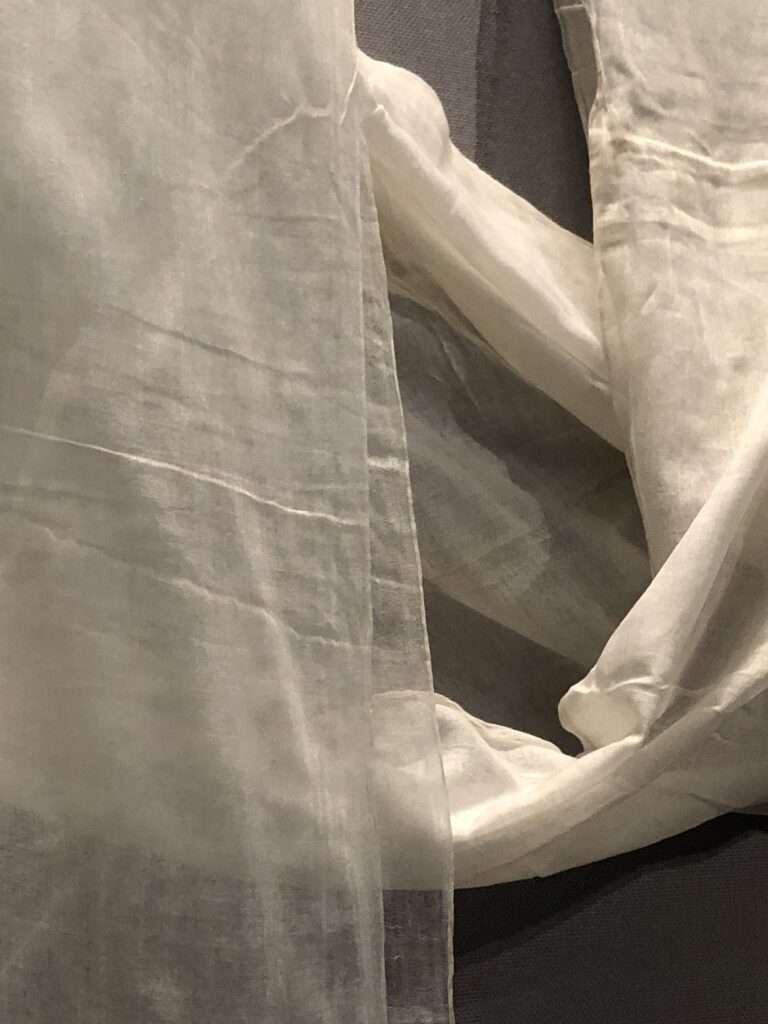

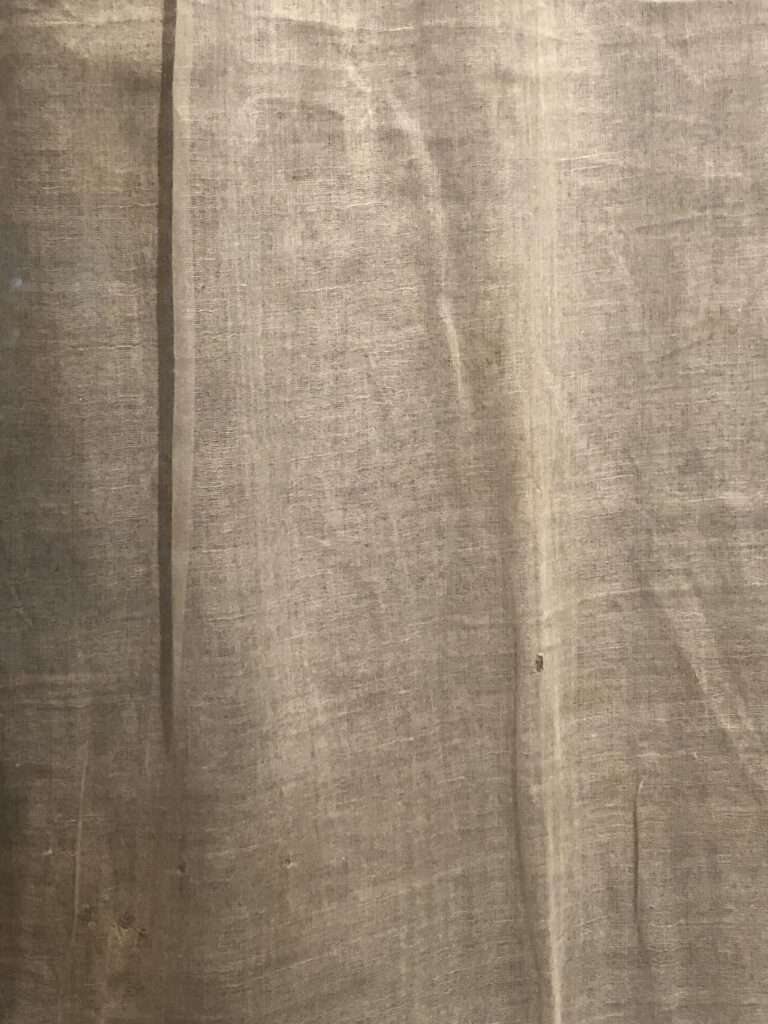

Although little physical evidence exists regarding the use of Bengal textiles in British fashion during the 17th and 18th centuries, many fashionable ladies’ items from the later Regency period, made from Indian muslins, are still preserved in museums and collections worldwide. This period, from 1790 to 1820, coincided with Jane Austen’s writing of her famous novels, in which she often mentions wearing muslin garments. This connection to literary history adds to the interest in the historical Bengal textiles. The Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities notes that Indian textiles were at the height of fashion in the late 18th century, with over 1.25 million Indian cloths exported to Britain in 1814 alone. Indian muslin, a lightweight cotton, was used for various items such as ruffles, cravats, handkerchiefs, gowns, and ladies’ dresses. Both men and women wore muslin, though it was more popular among women. Newspaper reports, such as The Guardian’s article on August 3, 1821, described a dress made from four types of muslin, demonstrating the high fashion status of Indian fabrics like muslin.

In addition to being used in British fashion and everyday life, the Indian textiles imported by the East India Company also became a valuable commodity for trade. Some textiles were consumed domestically, while others were re-exported to various parts of the world, including for the purchase of African slaves. While it is known that most of the textiles re-exported to Africa came from Gujarat or Madras, the significant volume of textiles imported from Bengal suggests that a portion of the re-exported textiles also originated from there. Between 1720 and 1740, for instance, it is estimated that 30-40% of the Indian textiles imported by the East India Company were re-exported to Africa.

According to Bhishnupriya Gupta’s figures on the number of textile piece goods from India and KN Chaudhury’s data on the total value of exports from Asia by the East India Company, it is evident that the majority of the textiles imported by Britain were from Bengal. Gupta reported that out of the 3,130,000 pieces of Indian textiles imported by Britain over a twenty-year period, 2,066,000 (66%) came from Bengal. It might be the Bengal’s share of the East India Company’s exports from India was approximately 70% during the same period. Additionally, Prasannan Parthasarathi stated that during that time, Indian textiles accounted for about one-third of British exports to Africa, with the quantity of Indian textiles sold in West Africa increasing significantly in the second half of the eighteenth century due to the expansion of the slave trade. This implies that there is a connection between textiles produced by Bengal weavers and the slave trade, although the proportion of textiles that were re-exported to Africa from western India would have been higher than that of Bengal textiles.

why Dhaka muslin disappeared

■ In the late 18th century, the British East India Company gained control over Bengal, which included the production of Dhaka muslin.

■ British policies such as high tariffs and restrictions on Indian textile imports to Britain, and the introduction of cheaper British textiles, had a significant impact on the demand for Dhaka muslin.

■ The Industrial Revolution in Britain, which began in the late 18th century and continued into the 19th century, also played a role in the decline of Dhaka muslin. New technologies and machinery allowed British manufacturers to produce textiles on a larger scale and at a lower cost, making it difficult for hand-woven muslin to compete.

■ In addition, the British encouraged the cultivation of cash crops such as indigo and jute in Bengal, which took up valuable farmland previously used for growing the cotton used in Dhaka muslin production

■ The Great Famine of 1873-74 in Bengal, which was exacerbated by British policies and actions, led to the deaths of millions of people and further weakened the local economy and textile industry, including Dhaka muslin production.

■ The final blow came with the outbreak of a fungal disease called “fusarium wilt” in the early 20th century, which destroyed the cotton crop and made it impossible to continue the production of Dhaka muslin.

In summary, the decline and disappearance of Dhaka muslin can be attributed to a combination of factors, including British policies and competition from cheaper British textiles, the Industrial Revolution, the cultivation of cash crops, and the devastating effects of the Great Famine and fungal disease.

During the era of Company rule, the East India Company brought in British-made cloth to the Indian subcontinent but couldn’t keep up with the local muslin industry. To suppress the muslin industry, the Company administration implemented various policies, leading to a decline in muslin production. Some have alleged that Bengali weavers had their thumbs chopped off, but historians have refuted this as a misinterpretation of a report by William Bolts in 1772. As a consequence of these policies, the quality, finesse, and production volume of Bengali muslin declined, persisting even after India shifted from Company rule to British Crown control.

THE REVIVAL OF DHAKA MUSLIN

Bangladesh is reviving a fabric that was once worn by Mughal emperors, Marie Antoinette, and Jane Austen, but was believed to be lost forever. The fabric, called Dhaka muslin, is being carefully produced using wooden spinning wheels and hand-drawn looms.

Dhaka muslin was made from incredibly fine threads, so much so that according to popular folklore in European parlors, a change in light or a sudden rain shower could make its wearer appear naked.

The production of this textile was once a source of great wealth in the areas where it was woven. However, in order to revive it, botanists had to embark on a worldwide search for a plant that was believed to be extinct.

“Nobody knew how it was made,” said Ayub Ali, a senior government official helping shepherd the revival project. We lost the famous cotton plant, which provided the special fine yarn for Dhaka muslin,”

According to historians, the muslin trade was once responsible for transforming the Ganges delta and present-day Bangladesh into one of the wealthiest regions in the world. Flowing dress garments made from the cloth were worn by generations of the Mughal dynasty in India, before enchanting European aristocrats and other notable figures in the late 18th century.Muslin shawls, such as the one supposedly hand-embroidered by Pride and Prejudice author Jane Austen herself, are on display at her former home in Hampshire. Additionally, a 1783 portrait of Marie Antoinette depicts the French queen in a muslin dress.However, the industry collapsed in the years following the East India Company’s conquest of the Bengal delta in the 18th century, which paved the way for British colonial rule. The mills and factories that arose in England after the Industrial Revolution produced much cheaper textiles, and European tariffs decimated the foreign market for the delicate fabric.

The painstaking effort to revive Bangladeshi muslin began with a five-year search for the specific flower required to weave the fabric, which only grows near Dhaka, the capital city. According to Monzur Hossain, the botanist who led the effort, “muslin can’t be woven without Phuti carpus cotton. So to revive Dhaka muslin, we needed to find this rare and possibly extinct cotton plant.”

Hossain’s team consulted a seminal book on plants by the 18th-century Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus and a later historical tome on Dhaka muslin to narrow down a candidate from 39 different wild species collected from around Bangladesh. Since local museums lacked any specimens of Dhaka muslin clothing, Hossain and his colleagues had to travel to India, Egypt, and Britain for samples.

At the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, curators showed them hundreds of pieces imported from Mughal-era Dhaka by East India Company merchants. Genetic testing revealed that the missing plant was already in their possession, having been found by the botanists in the riverside town of Kapasia, north of the capital.Hossain’s team is now growing the plant in experimental farms in an attempt to increase yields and scale up production.

The revival of Bangladeshi muslin faced an immediate challenge – finding skilled weavers who could handle the plant’s ultra-fine threads. Bangladesh’s textile industry, while still one of the world’s largest, no longer catered to royalty or international elites. Instead, it now focused on fast fashion for major brands like H&M and Walmart. To revive muslin, the project had to source artisans from the small cottage industry of spinners and weavers working with fragile threads, and candidates were found in villages around Dhaka where intricate saris are made from jamdari, a fine cotton produced in a similar way to muslin. The team took months to master the craft, working with threads four or more times finer than jamdari. Weaving an inch or less of cloth required two people to work non-stop for eight hours, requiring supreme concentration and a steady hand. While the intense labor involved makes muslin a boutique product, the government has garnered some interest from established industry players to help bring down costs and increase production.

A 300-thread count sari woven out of a hybrid Dhaka muslin thread Courtesy of Bengal Muslin

‘The attempt to revive a lost art is intrinsic to our national sense of pride’

– Shahidul Alam, CEO, Drik

Drik PL is the brainchild of renowned photographer and activist, Shahidul Alam, who formed it in response to the stereotypical portrayals of the global south, ‘the majority world’, by the western media. Established in 1989, it is a distinctive multimedia organisation that has made provision of high quality customer services and challenging inequality central to its agenda. Its major areas of expertise are advocacy and awareness campaigns, production of communication material and training. Using the power of the visual medium and its wide experience, Drik is able to provide a one-stop effective multimedia service through its multiple departments. Saiful Islam, was the CEO of Drik PL between 2012 and 2016 and during his tenure, early in 2014, he assembled a team consisting of photographers, researchers, curators and a range of contributors who quickly formed into an incredibly dynamic and creative group of cultural activists focussed on bringing muslin alive. This was the birth of Bengal Muslin. Today, Bengal Muslin remains an initiative supported by Drik and led by Saiful Islam as the project’s Managing Director and Kamal Hossen as the Manager.