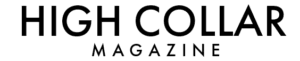

Poplin or Broad ?

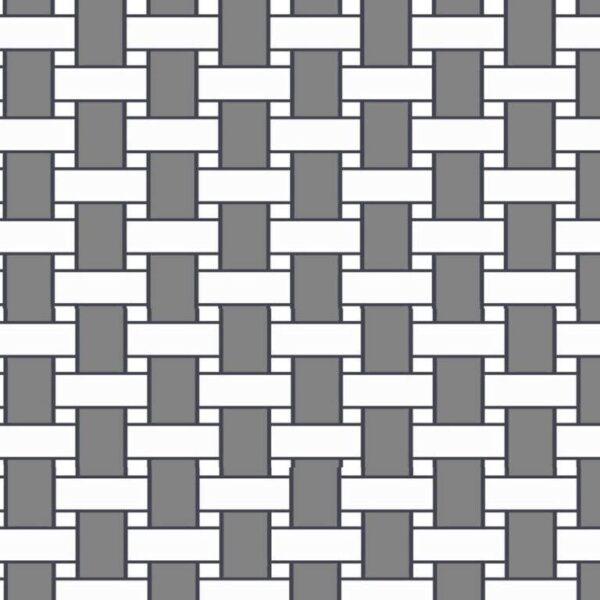

Poplin, also known as tabinet or tabbinet, is a distinctive fabric made from wool, cotton, or silk, characterized by its vertical warp and horizontal weft. This fabric has evolved over time, now commonly signifying a robust, plain weave material from any fiber or blend, often featuring crosswise ribs for a cord-like texture.

Historically, poplin was crafted with a silk warp and a worsted yarn weft. This combination resulted in a fabric with a ribbed texture, similar to rep, enhancing the silky surface with depth and a plush feel. The ribs extend across the fabric’s width from edge to edge. Notably, in Britain, woolen yarn from Suffolk’s spinners was combined with silk in Dublin to produce tabinet.

Modern poplin is versatile, made from wool, cotton, silk, rayon, polyester, or blends thereof. Its simple under/over weave presents a smooth surface, especially when made with weft and warp threads of identical material and size. This makes poplin shirts particularly easy to iron and resistant to wrinkles. Poplin’s utility extends beyond clothing to luxurious upholstery, often utilizing coarser filling-yarns in a sturdy weave for added texture.

ポプリン、またタビネット(タビネ)とも呼ばれる、は細かい(しかし厚い)ウール、コットン、またはシルクの生地で、縦糸が垂直方向に、横糸が水平方向に配置されています。現在では、この名前はあらゆる繊維や混合物の平織りの強い素材を指し、一般的には横方向の筋が特徴的なコーディングされた表面を持ちます。伝統的にポプリンは、絹の経糸とウールの緯糸から成り立っていました。この場合、緯糸が太いコードの形をしているため、生地はレップのような筋のある構造を持ち、絹の表面の光沢に深みと柔らかさを与えます。筋は生地の端から端まで横切っています。イギリスでは、サフォークの紡績業者からのウールの糸がダブリンに送られ、タビネットに織り込まれていました。

ポプリンは現在、ウール、コットン、シルク、レーヨン、ポリエステル、またはこれらの混合物で作られています。平織りの下/上織りであるため、緯糸と経糸が同じ素材とサイズである場合、生地はリブのない平織りの表面を示します。この素材から作られたシャツはアイロンがかけやすく、しわになりにくいです。ポプリンはドレス用途や、平織り/硬質織りで粗い充填糸を使って形成される豪華な室内装飾用途に使用されます。

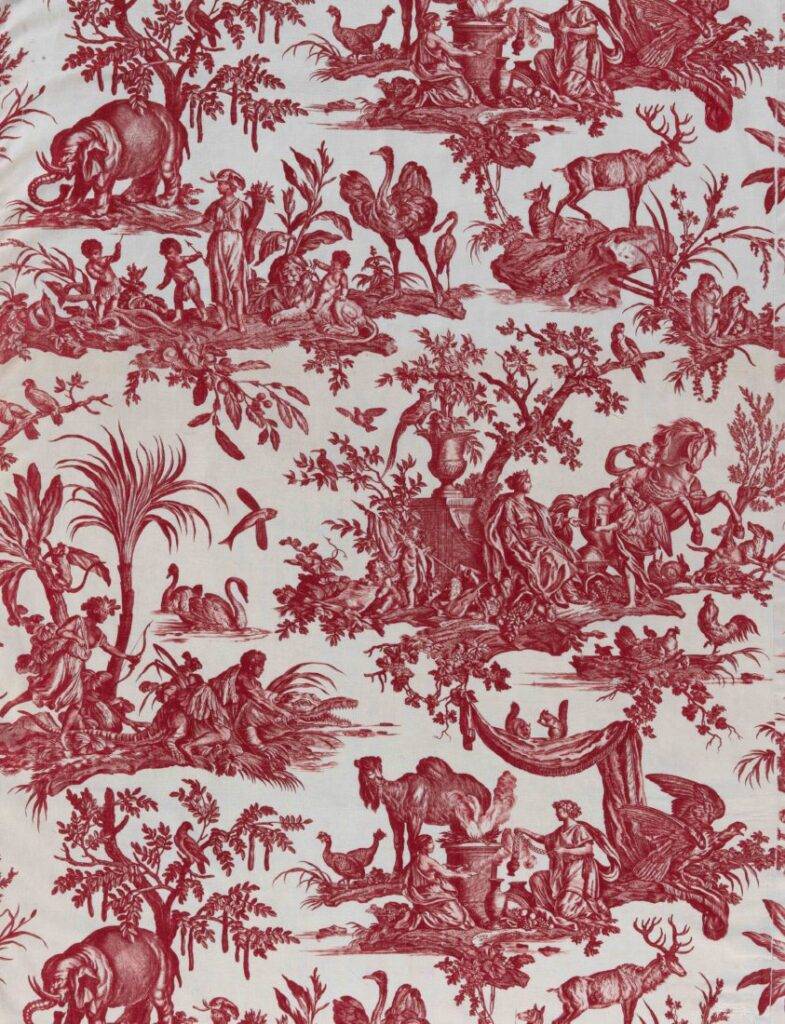

The Provencal fabrics, known for reflecting the sunny and vibrant colors of Southern France, have an interesting history that intertwines with global trade and cultural exchange. Initially, these textiles didn’t come from Provence but were introduced from India and Persia in the early 17th century. The colorful printed fabrics, first imported via Marseille, became a sensation despite their high cost. Known as ‘Indiennes’, their popularity spread rapidly across France, creating a demand that imports couldn’t satisfy.

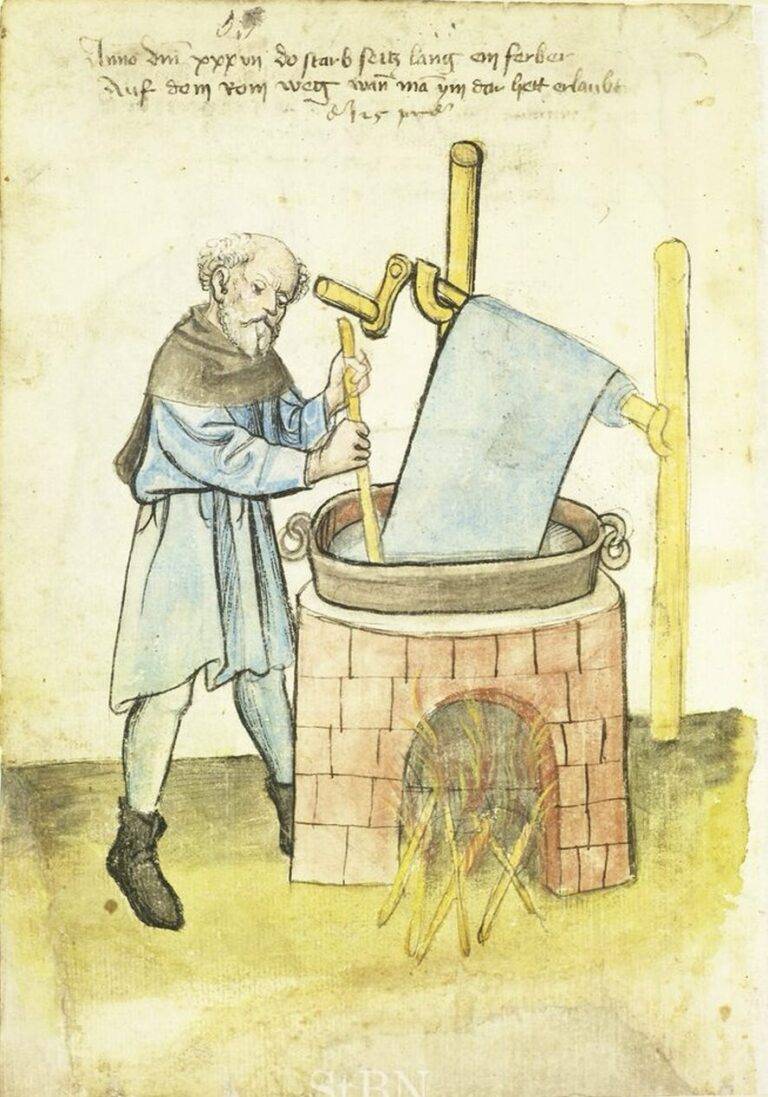

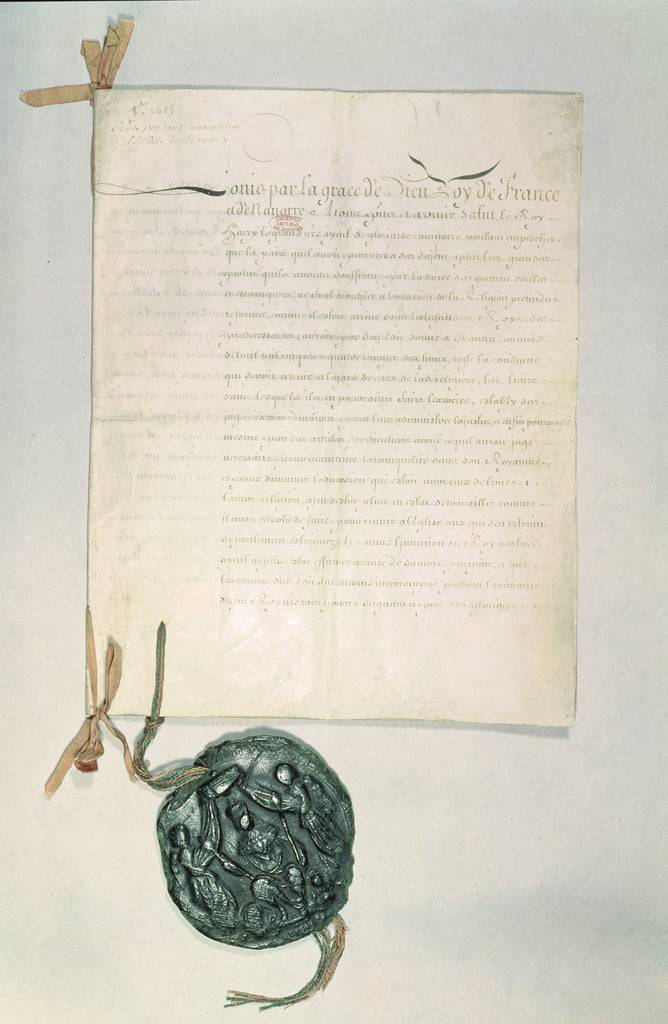

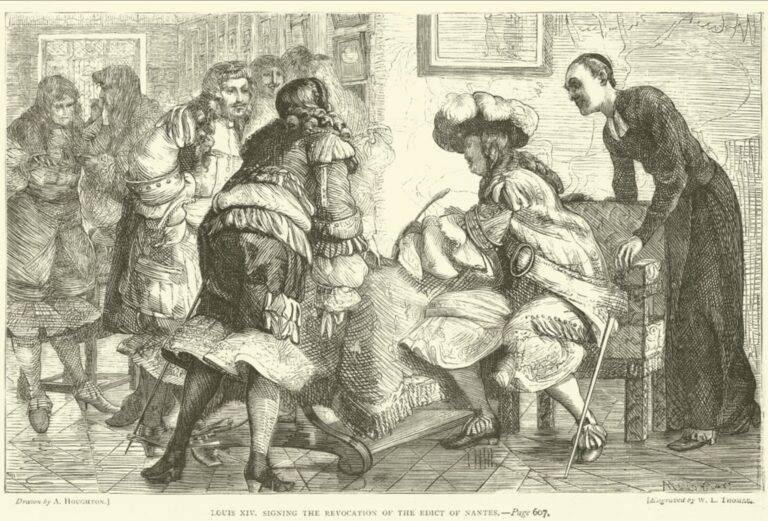

Recognizing the commercial potential, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the Finance Minister under King Louis XIV, founded the Compagnie Francaise des Indes Occidentales (East India Company) in 1664. He also brought Armenian dyers and fabric makers to France to share their expertise with local artisans. However, this craze for Indiennes led to the decline of the traditional French silk and wool industries, prompting a ban on both the import and production of Indiennes in 1686. This ban inadvertently boosted smuggling.

The manufacturers, adapting to the ban, moved their operations to Avignon, then under the Vatican’s jurisdiction, not France’s. There, they hired Jean Althen, an Armenian dyer, who introduced the use of the red madder dye known as garance. The artisans in Avignon quickly mastered new production techniques, including card printing on fabric. The ban on Indiennes was eventually lifted in 1759, leading to a resurgence in their popularity.

Provencal weavers began adapting traditional Indian designs to local tastes, evolving what we now recognize as the classic Provencal style. This style, inspired by the natural landscapes of Provence – the purple of lavender fields, the silver-green of olive groves, the yellow of sunflowers and mimosas, and the rich ocher and crimson of Roussillon’s soil – became emblematic of the region. Each area in Provence, like Manosque, Carpentras, and Lubéron, contributed its distinct patterns and styles. Some fabrics even bear the names of individual weavers, such as Marius or Orane.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, an influential figure in French history, served as the First Minister of State from 1661 until his death in 1683 during King Louis XIV’s reign. His legacy, known as Colbertism, is a significant contribution to the mercantilist economic doctrine and has had a lasting impact on France’s political and economic organization.

Born in Reims, Colbert’s career took a significant turn when he was appointed the Intendant of Finances on May 4, 1661. Following Nicolas Fouquet’s arrest for embezzlement, Colbert stepped into the newly created role of Controller-General of Finances, marking the end of the Superintendent of Finances office. He was instrumental in developing France’s domestic economy, notably by increasing tariffs and promoting large-scale public works. Additionally, he played a key role in ensuring the French East India Company’s access to international markets, facilitating the import of essential goods such as coffee, cotton, dyewoods, fur, pepper, and sugar.

Colbert’s policies were geared towards creating a favorable trade balance and expanding France’s colonial possessions. In 1682, he initiated a project that led to the establishment of the Code Noir in 1685, two years posthumously, to regulate slavery in the colonies. He also founded France’s merchant navy and became Secretary of State of the Navy in 1669.

His market reforms were substantial, including the establishment of the Manufacture royale de glaces de miroirs in 1665 to end the importation of Venetian glass. Once the national glass manufacturing industry stabilized, the import of Venetian glass was prohibited in 1672. Colbert also boosted the Flemish cloth manufacturing expertise in France, founding royal tapestry workshops at Gobelins and supporting those at Beauvais. He issued over 150 edicts to regulate guilds and was a key figure in founding the Académie des Sciences in 1666. A member of the Académie française from March 1, 1667, until his death, he was succeeded in the 24th seat by Jean de La Fontaine. His son, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Marquis de Seignelay, followed in his footsteps as Navy Secretary.

インディエンヌ(発音: /ˌændiˈɛn/, アンディエン;フランス語: [ɛ̃.djɛn]、「東インドから来たもの」の意)は、17世紀から19世紀にかけてヨーロッパで製造された、印刷または描画された織物の一種で、もともとインドで作られた類似の織物に触発されていました(そのためこの名前が付けられました)。フランスでは、マドラス、ペキン(北京の意)、ペルス(ペルシャの意)、ググラン、ダマス、シルサクスなど、さまざまな名前でも呼ばれていました。織物の印刷に使われる元のインドの技術は、染料を定着させるためにモルダントや金属塩を使用する長く複雑な工程を必要としました。美しい鮮やかな色は、赤色にはガランス植物、青色にはインディゴ、黄色にはガウデを使用していました。

インディエンヌは非常に人気があり、やがて輸入代替が試みられました。1640年に、アルメニアの商人がマルセイユの港でインドの織物印刷技術を導入しました。この技術は後に1670年にイングランド、1678年にオランダでも採用されました。

しかし、インディエンヌのフランスへの輸入と生産は、現地のウールや絹の織物産業を保護するために1686年に王立令によって禁止されました。禁止にもかかわらず、インディエンヌの生産は地元で続けられ、1759年に再び合法化されました。フランスにおけるインディエンヌの主な生産地はマルセイユでした。

ジャン=バティスト・コルベールは、1661年から1683年までのルイ14世の治世下でフランスの第一国務大臣を務めた重要な政治家でした。彼のコルベール主義として知られる政治・経済組織への影響は、重商主義の一形態として特徴付けられ、フランスの政治と市場に長期的な影響を与えました。ランス出身のコルベールは、1661年5月4日に財務監督に任命されました。ニコラ・フーケの横領で逮捕された後、新設された財務総監の地位を引き継ぎ、財務監督官の職を廃止しました。彼は関税を引き上げ、大規模な公共事業を推進することで国内経済を発展させ、フランス東インド会社が国際市場にアクセスし、コーヒー、綿、染料木、毛皮、胡椒、砂糖などの重要な商品を入手できるようにしました。彼の政策は貿易収支を好転させ、フランスの植民地領有を拡大することを目指しました。1682年、コルベールは植民地における奴隷制を規制するコード・ノワールのプロジェクトを開始し、彼の死後2年後の1685年に制定されました。また、彼はフランスの商船隊を創設し、1669年に海軍国務大臣に就任しました。

彼の市場改革には、1665年にヴェネツィアガラスの輸入を代替するために王立鏡ガラス製造所を設立することが含まれ、国内のガラス製造業が安定した1672年にヴェネツィアガラスの輸入を禁止しました。また、フランドルの布製造技術をフランスに導入し、ゴブランの王立タペストリー工場を設立し、ボーヴェの工場を支援しました。彼はギルドを規制するために150以上の勅令を発しました。また、1666年に科学アカデミーを彼の提案により設立しました。彼は1667年3月1日から死去するまでフランス学士院の第24席に座り、ジャン・ド・ラ・フォンテーヌが彼の死後に選出されました。彼の息子、ジャン=バティスト・コルベール(セーニュレ侯爵)は海軍大臣として彼の後を継ぎました。

Avignon, known in French as [aviɲɔ̃] and Provençal as Avinhon (Classical norm) or Avignoun (Mistralian norm), with the Latin name Avenio, serves as the administrative center of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region in southeastern France. Situated on the left bank of the Rhône River, Avignon had a population of 93,671 as of the 2017 census. The historic town center, surrounded by medieval walls, is home to approximately 16,000 people, as estimated by Avignon’s municipal services. It ranks as the 35th-largest metropolitan area in France, according to INSEE, with 337,039 inhabitants (2020), and the 13th-largest urban unit with 459,533 inhabitants (2020). Notably, its urban area experienced the most rapid growth in France from 1999 to 2010, with a 76% increase in population and a 136% expansion in area. The Communauté d’agglomération du Grand Avignon, comprising 16 communes, had a population of 197,102 in 2022.

From 1309 to 1377, Avignon was a pivotal location during the Avignon Papacy, hosting seven successive popes. In 1348, Pope Clement VI acquired the town from Joanna I of Naples. The city remained under papal control until 1791 when it was incorporated into France amid the French Revolution. Today, Avignon is not only the capital of the Vaucluse department but also notable for being one of the few French cities that have preserved its city walls, earning it the nickname ‘La Cité des Papes’ (The City-State of Popes).

Avignon’s historic center, encompassing the Palais des Papes, the cathedral, and the Pont d’Avignon, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995 due to its significant architecture and historical relevance in the 14th and 15th centuries. The city is a prominent tourist destination, famed for its medieval monuments and the annual Festival d’Avignon (or “Avignon Festival”) along with its companion, the Festival Off Avignon—one of the world’s largest performing arts festivals.

アヴィニョンはフランス語で[aviɲɔ̃]、プロヴァンス語でアヴィニョン(古典的な表記法)またはアヴィニョウン(ミストラル式表記法)と呼ばれ、ラテン語ではアヴェニオという名前があります。これは、フランス南東部のプロヴァンス=アルプ=コート・ダジュール地域のヴォクリューズ県の県庁所在地です。ローヌ川の左岸に位置するアヴィニョンの人口は、2017年の国勢調査で93,671人でした。歴史的な町の中心部には、中世の城壁に囲まれ、およそ16,000人(アヴィニョン市の公共サービスによる推定)が住んでいます。フランス国立統計経済研究所(INSEE)によると、2020年の時点でフランスで35番目に大きな都市圏を形成し、337,039人の住民がいます。また、都市単位では459,533人の住民を擁し、フランスで13番目に大きいです。特筆すべきは、1999年から2010年までの間に人口が76%増加し、面積が136%拡大するなど、フランスで最も急速に成長した都市圏でした。16のコミューンで構成されるアヴィニョン大都市圏コミュニティは、2022年には197,102人の人口を有しています。

1309年から1377年にかけてのアヴィニョン捕囚の間、7人の連続する教皇がアヴィニョンに居住し、1348年には教皇クレメント6世がナポリのジョヴァンナ1世から町を購入しました。フランス革命中の1791年まで教皇の支配が続き、その後フランスの一部となりました。現在、アヴィニョンはヴォクリューズ県の県都であり、その市壁を保存している数少ないフランスの都市の一つです。これが、「教皇の都市国家」としても知られる理由です。

アヴィニョンの歴史的中心地は、パライ・デ・パプ(教皇宮殿)、大聖堂、アヴィニョン橋を含み、14世紀から15世紀にかけてのその建築と歴史的重要性から1995年にユネスコの世界遺産に指定されました。年間を通じて開催されるアヴィニョン祭(「アヴィニョン・フェスティバル」として一般に知られている)と、それに伴うアヴィニョン・オフ・フェスティバル(世界最大級のパフォーミングアートの祭典の一つ)は、この町を主要な観光地として知られるようにし、中世の記念碑とともにアヴィニョンの名声を高めています。

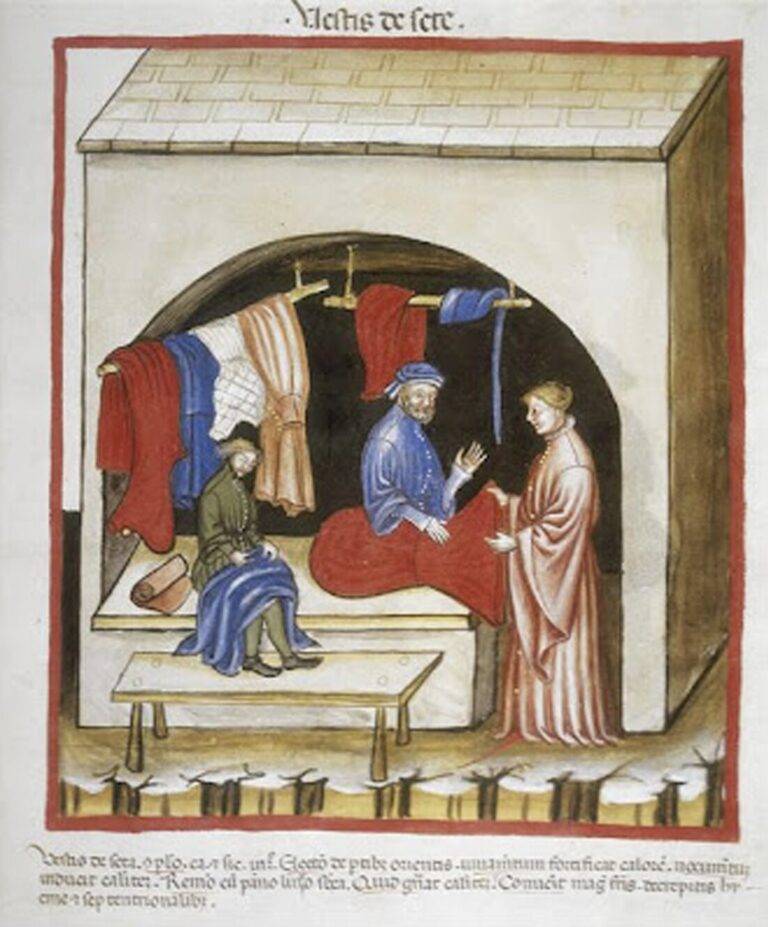

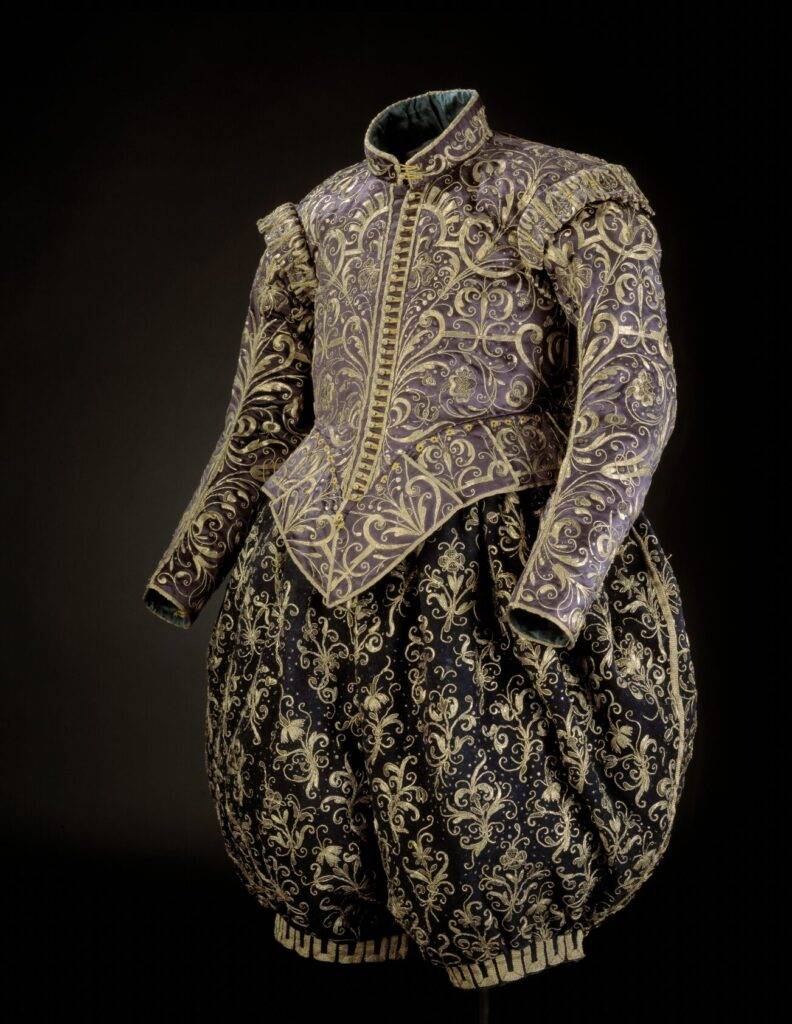

Italian silk fabric, known for its high quality, was costly due to the expensive raw materials and intricate production methods. This silk struggled to meet the evolving demands of French fashion, which leaned towards lighter, more affordable materials. Although Italian silk remained highly valued for furnishings and its vibrant dyes, local production of alternative textiles began.

Italian city-states like Venice, Florence, and Lucca, renowned for luxury textiles, inspired Lyon’s rise as a silk hub in France. In 1466, King Louis XI aimed to establish a national silk industry in Lyon, bringing in many Italian artisans, especially from Calabria. The renowned weavers of Catanzaro were even invited to Lyon to share their weaving techniques. Jean Le Calabrais introduced the drawloom in France during this period.

Despite protests from Lyon’s residents, Louis XI initially shifted silk production to Tours, though it remained a minor industry there. His goal was to lessen France’s hefty trade deficit with Italy, which was costing 400,000 to 500,000 golden écus annually. Around 1535, under Francis I, Lyon’s silk trade was invigorated by a royal charter granted to merchants Étienne Turquet and Barthélemy Naris. In 1540, Lyon received exclusive rights to silk production, eventually emerging as the European silk trade’s epicenter and known for its esteemed fashions from the 16th century onwards.

Lyon’s silk industry began creating unique designs, moving away from traditional Oriental styles and incorporating landscape motifs. By the mid-17th century, the industry was booming with over 14,000 looms in operation, supporting a third of Lyon’s populace.

イタリアのシルク生地は、その高品質で知られていましたが、原材料と製造工程のコストが高く、非常に高価でした。このシルクは、より軽く、安価な素材を求めるフランスのファッションの進化に追いつくことができませんでした。イタリアのシルクは家具用として、またその鮮やかな染料のために長い間高く評価され続けましたが、代わりのテキスタイルの生産は地元で始まりました。ヴェネツィア、フィレンツェ、ルッカなどのイタリアの都市国家が高級テキスタイルの中心地として名を馳せたように、リヨンはフランスのシルク市場で類似の役割を果たすようになりました。1466年、ルイ11世はリヨンで国内シルク産業を確立することを決定し、多くのイタリア人労働者、特にカラブリアからの労働者を雇用しました。カタンザーロの名工の名声はフランス中に広がり、彼らは織り技術を教えるためにリヨンに招かれました。この時期にフランスに現れたドロールームは、ジャン・ル・カラブレによって導入されました。

リヨンの住民の抗議に直面して、ルイ11世はシルク生産をツールへ移すことに同意しましたが、そこでの産業は比較的限定的なものでした。彼の主な目的は、イタリア諸国との間のフランスの巨額の貿易赤字を減らすことでした。この赤字は年間40万から50万ゴールド・エキュにものぼりました。1535年頃、フランソワ1世の下で、商人エティエンヌ・トゥルケとバルテルミー・ナリスにリヨンでのシルク取引を発展させるための王室特許が与えられました。1540年、王はリヨン市にシルク生産の独占権を与えました。16世紀から、リヨンはヨーロッパのシルク貿易の首都として登場し、多くの評判の高いファッションを生み出しました。リヨンのシルク産業は独自のデザインを作り出し始め、従来の東洋風のスタイルから離れ、風景を取り入れたモチーフに移行しました。17世紀半ばには、産業は盛んになり、リヨンの人口の3分の1を支える14,000以上の織機が稼働していました。

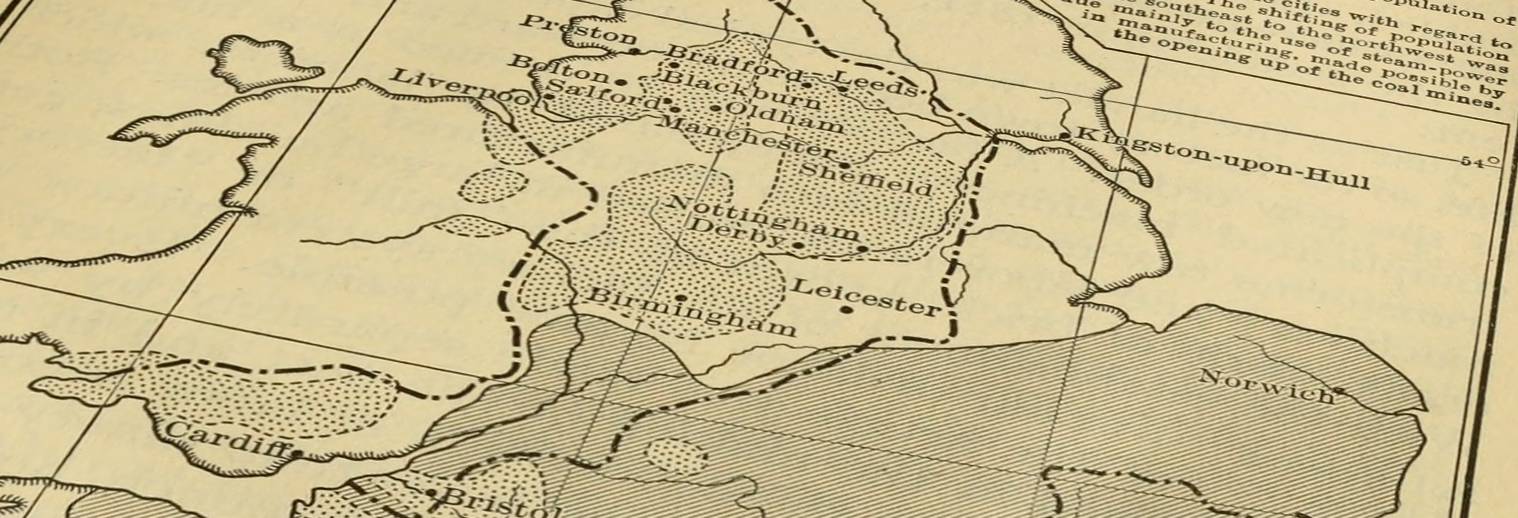

The Industrial Revolution’s onset was marked by a significant surge in the textile industry, led by Great Britain’s cotton sector. This period saw remarkable technological advancements, although they varied across different stages of fabric production, driving further complementary innovations. For instance, spinning technology advanced much more rapidly than weaving. Unlike other textiles, the silk industry didn’t benefit from these spinning innovations, as silk weaving didn’t require pre-spinning. Moreover, producing silver and gold silk brocades was a highly intricate process, with each color needing its own shuttle. The 17th and 18th centuries saw efforts towards simplifying and standardizing silk manufacturing, with many subsequent advancements. In 1775, the punched card loom by Bouchon and Falcon emerged, later refined by Jacques de Vaucanson. Joseph-Marie Jacquard further enhanced these designs, introducing the groundbreaking Jacquard loom. This loom used a series of punched cards processed mechanically in sequence, a precursor to modern computer programmability. These punched cards were later adopted in computing, remaining prevalent until the 1970s. From 1801, thanks to the Jacquard loom, embroidery-like designs became highly mechanized, enabling mass production of complex patterns.

The Jacquard loom faced initial backlash from workers fearing unemployment but soon became essential in the industry. Declared public property in 1806, Jacquard received a pension and royalties for each loom. By 1834, Lyon alone had 2,885 Jacquard looms. The 1831 Canut revolt in Lyon, sparked by worker discontent, preluded larger uprisings during the Industrial Revolution, culminating in a bloody military repression.

The European silk industry began to decline due to the emergence of silkworm diseases in 1845, leading to an epidemic. Diseases like pébrine (Nosema bombycis), grasserie (a virus), flacherie (from infected mulberry leaves), and white muscardine disease (Beauveria bassiana) devastated the industry. The epidemic, initially affecting silkworms, eventually spread to mulberry trees. Jean-Baptiste Dumas, the French agriculture minister, tasked Louis Pasteur in 1865 to study these diseases. After years of research, measures were implemented under Pasteur’s guidance, leading to a decline in the epidemic.

However, the rising cost of silkworm cocoons and a shift in bourgeois fashion trends in the 19th century led to the silk industry’s decline in Europe. The 1869 opening of the Suez Canal and a silk shortage in France made importing Asian silk, especially from China and Japan, more affordable. During the Long Depression (1873–1896), Lyon’s silk production fully industrialized, phasing out handlooms. The 19th century also saw advances in chemistry influencing the textile industry. The synthesis of aniline led to the creation of mauveine (aniline purple) dye and synthetic indigo. In 1884, Count Hilaire de Chardonnet invented viscose, an artificial silk, and opened a factory in 1891 for its production. Viscose, cheaper than natural silk, partially replaced it in various applications.

ABOUT THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

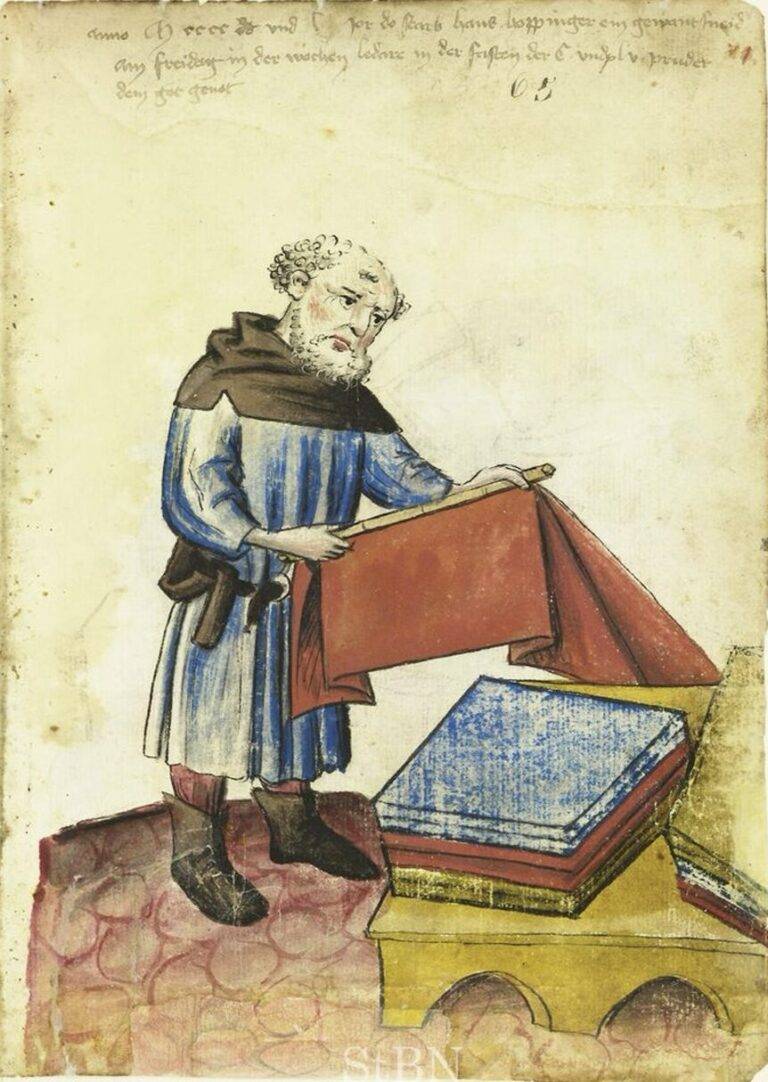

ブロードクロス、またはフラマン語でラーケンとも呼ばれる布地は、11世紀から中世全般を通じてブラバント公国(現在のフランドル)で製造されました。1400年以降、オランダのライデン(現在のネーデルラント)がヨーロッパのブロードクロス産業の最も重要な地として台頭し、産業が工業化された最初の例となりました。これは、生産過程が一つの工場だけで完結するのではなく、複数の段階にわたって中間財を生産する正確なタスク割り当てに従って行われたことを意味します。厳格な監視の下で行われた全工程は、一貫して高い品質を保ち、ライデンのブロードクロスを非常に人気のあるものにしました。1417年には、ハンザ同盟がライデンで承認されたブロードクロスのみを販売することを決定しました。しかし1500年頃には、特にイングランドをはじめとするヨーロッパの他の地域からの競争が増し、ライデンはそのリードを失いました。イタリアではフィレンツェがブロードクロス産業の重要な中心地となりました。

1500年頃には、イングランドの複数の地区、特に南東アングリアのエセックスやサフォーク、ウェストカントリー・クロージング地区(グロスターシャー、ウィルトシャー、イーストサマセットなど)、ウスター、コヴェントリー、ケントのクランブルックなどでブロードクロスが製造されました。これらのイングリッシュ・ブロードクロスは、ロンドンの商人冒険家会社によって主にアントワープへ未染色の布として大量に輸出されました。その後、フランドルで仕上げられ、染色され、北ヨーロッパ全域で販売されました。布は短い(24ヤード長)か長い(30ヤード長)のものがありました。

ウスターのブロードクロスの原料は、ヒアフォードシャーとシュロップシャーのウェールズ国境郡からの羊毛、いわゆるレムスター(つまりレオミンスター)ウールでした。ウェストカントリーのものはコッツウォルズから来ました。どちらのケースも、比較的劣悪な牧草地が、羊が望ましい特性を持つ羊毛を生産するように導いた結果でした。イングリッシュ・ブロードクロスの輸出は16世紀中頃に最高潮に達しましたが、その後一部の地域では他の種類の布の生産に移行しました。17世紀には、特に東ヨーロッパの通貨問題や不適切に考えられたコッケイン・プロジェクトにより、輸出市場での困難に直面し、ブロードクロスの生産は衰退しました。

ウスターは白いブロードクロスの生産地として残りましたが、ラドロウやコッツウォルズの一部など他の地域では「ウスターズ」と呼ばれる類似の布を生産し始めました。18世紀には、レヴァント会社がトルコとの貿易でフランスの競争により大きな打撃を受けた際、市場は大きな後退を経験しました。この時期から、ブロードクロスの生産は重要性を失いました。

11世紀から13世紀にかけてのフランドルは黄金時代を迎えました。地元の織工の勤勉さと商人の起業家精神のおかげで、フランドルの布はその非常に高い品質で知られ、ヨーロッパ全域やそれ以外の地域で大変な需要がありました。この産業は豊かなイタリアやスペインの商人や銀行家をフランドルの都市に引き寄せ、ヘントやイーペルの発展を資金提供し、ブルージュを北ヨーロッパで最も忙しい港へと変貌させました。しかし、14世紀に産業は停滞し、15世紀初頭までにはかつての栄光のほんの一部にまで減少しました。

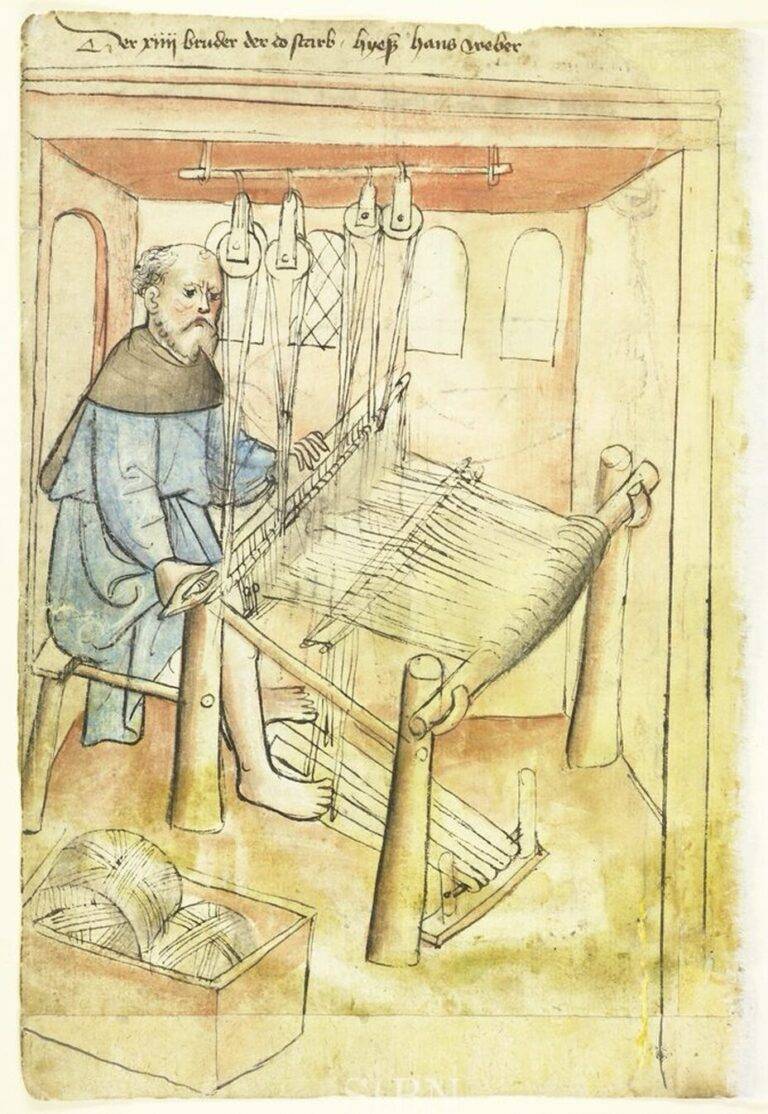

フランドルの布は長い間、高く評価されている商品でした。ローマ人がベルギカと呼んだ地域に入ったとき、地元民が織った高品質の布は男性のトガや女性のストラに使われ、非常に価値があるとされました。中世初期には、フランドルの主要な貿易相手国は北海とバルト海沿岸に位置しており、これらの地域は船で容易にアクセスできました。ロシアのノヴゴロドの市場にフランドルの布が現れた記録も存在します。この地位に貢献した要因はいくつかありました。低地諸国には、特に修道院や僧院において、古くからの工芸の伝統がありました。この地域の人口密度が比較的高かったため、住民は農業に加えて他の職業に従事する必要がありました。また、フランドルの地形は、特に新しく開墾されたポルダーでの羊の飼育に適していました。産業が成長するにつれ、町も成長しました。農村部の織工、紡績工、フラーは、盛んな布貿易が行われていたブルージュ、ヘント、イーペルに移住しました。11世紀には、従来の水平織機から新しい垂直織機への移行により、労働者の生産性が3倍になるという技術革命が起こりました。

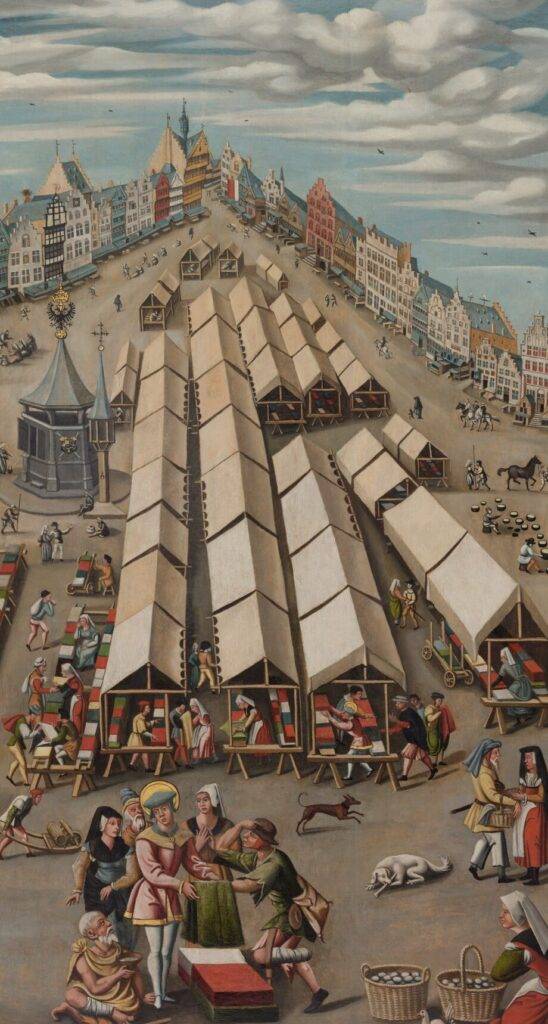

12世紀初頭には、フランドルの布商人はヨーロッパ南部を新たな輸出市場として目を向け、フランスのシャンパーニュ地方で開催される大規模なフェアに参加し始めました。これらのフェアは迅速にヨーロッパ大陸で最も商業的に重要なフェアとなり、低地諸国とイタリア(当時の二大商業ハブ)を結ぶ必要なリンクを提供しました。フェアは6つのイベントのサイクルで行われ、それぞれ6週間続きました。プロヴァンとトロワでそれぞれ2回、バール=シュル=オーブとランニで各1回開催されました。

- Banat Wool Broadcloth: Originating from India, this is a type of woolen broadcloth.

- Bridgwater (1450-1500): This lighter weight broadcloth was produced in England, Scotland, and Wales.

- Castor: A woolen broadcloth heavy enough for overcoats.

- Cealtar (Irish Gaelic): A thick, grey variety of broadcloth.

- Dunster (early 14th century): A specific type of broadcloth made in Somerset.

- Georgian Cloth (circa 1806): Named for the Georgian era in which it was produced.

- Haberjet (Middle Ages): A coarse wool broadcloth from England, associated with medieval monks.

- Habit Cloth: A fine wool broadcloth from Britain, typically used for women’s riding habits.

- Lady’s Cloth: A lighter weight broadcloth, initially made in lighter shades.

- Poole Cloth (19th century onwards): Named after the tailoring establishment Henry Poole & Co (founded 1806), this broadcloth is known for its clear finish.

- Suclat: A cotton broadcloth made in Europe and popular in the East Indian market.

- Superfine (18th century onwards): A merino broadcloth used in men’s tailoring.

- Tami: A broadcloth made in China.

- Taunton (16th century): Produced in Taunton, available in medium or coarse grades, with a legally fixed weight of 11oz. per yard.

- Tavestock (circa 1200-1350): A historic variety of broadcloth.

- Western Dozen (16th century): Another term for Tavestock broadcloth.

19世紀のイングランドの工業化時代と同様に、異なる階級間の不均衡が存在しました。一方の極端には、布産業に関心を持つ裕福な家族のメンバーである貴族がおり、彼らは織物の町を大きく支配しており、都市の中心部にある豪華な宮殿のような建物で贅沢な生活をしていました。もう一方の極端には、工場がある周辺地区に追いやられた織物労働者がいました。このグループ内にも分裂がありました。織り手は紡績工、フラー(洗い張り職人)、糸作り職人のサービスを利用していました。ヘントでは、織り手とフラーの間の対立が何度も社会的、政治的な不安を引き起こし、両グループは政治的影響力を求めて争いました。織り手は常に優位に立ちました。フラーは特に賃金が低く、その仕事は汚く、屈辱的であると見なされていました。

14世紀から16世紀にかけてのローカントリーで使用された伝統的な方法では、フラーは織られた布を、熱い水、フラーの土(粘土のような物質)、尿を含む大きな容器に入れました。フラーはこの悪臭を放つ混合物の中で布を3日間、あるいは非常に豪華な布の場合はそれ以上踏みつけました。そのため、フラーの仕事が最も低く、最も屈辱的な職業と見なされるのは驚くことではありませんでした。さらに、この段階での染色により、フラーは手足が永久に変色することがありました。

貴族と織物労働者の間の不平等は、反乱を引き起こしました。1252年と1274年には、ヘントの貧しい布工たちが自分たちの権利の欠如に抗議しました。1280年には、フランダースのほぼすべての織物町で労働者が路上に出て、劣悪な労働条件に抗議しました。ジャック・ヴァン・アルテヴェルデの時代、50年後になってようやくフラマン語圏の織物労働者の地位が改善されました。しかし、その時にはもう遅く、フランダースの織物産業はすでに衰退していました。

フランダースの布産業の衰退には三つの主な理由がありました。第一に、何年もの間徐々に蓄積された砂によりブルージュ港が埋まっていくことが問題でした。ブルージュ港が使えなくなることへの懸念の中で、1180年に近くのダンメ港が建設されました。しかし、13世紀の終わりまでにダンメも大型のイタリア船を受け入れることができなくなりました。その後、1290年にはさらに遠くのスリュース港が開港しましたが、この改善は一時的なものでした。スリュース港もまた埋まり、大型船は沖合の島に錨を下ろし、その貨物をバージでスリュースに輸送する必要があり、時間と費用の無駄が生じました。結果としてブルージュはその地位を失い始め、布の輸出プロセスは以前ほど簡単ではなくなりました。第二に、港の便利さが低下すると、イタリアの商人や銀行家たちはより戦略的で、大型船に適したアントワープへと移動しました。アントワープはフランスを通らずにドイツを経由する新しい陸上貿易路へのアクセスが容易であり、布産業よりも利益の大きい他の投資機会を提供しました。衰退の第三の理由は、イングランドとフランスの間の政治的緊張で、これがしばしばフランダースの経済に影響を与えました。イングランドによるフランダースへのウール輸出の禁輸は、この紛争における頻繁で効果的な戦術でした。高品質なイングランドのウールがなければ、高品質なフランダースの布も存在しませんでした。

さらに、フランダースの布は初めて真剣な競争に直面しました。イングランド自体が独自の布産業を発展させていました。それを保護するため、イングランドはウールの輸出税を徐々に増やしました。1275年には1袋(166kg)あたり6シリング8ペンスだった税金は、1341年には1袋あたり46シリング8ペンスにまで上昇しました。イングランドのウールに代わる安価な代替品が見つかりました。それはスペインのメリノ羊から来たものでした。フランダースへの輸入により、スペインの商人たちがブルージュ、ヘント、イーペルに現れました。しかし、スペインのウールは中品質の衣類には適していましたが、フランダースの産業が基盤としていた高級ウール製品には適していませんでした。フランダースの独占は終わりました。産業の低迷により、一部のフランダースの織物労働者はより良い機会を求めてイングランドに移住しましたが、多くは改善を待って留まりました。彼らの状況は14世紀、黒死病による人口減少の後に改善されました。労働力不足により市場の地位が向上し、したがって労働条件もより有利になりました。しかし、フランダースの布産業の黄金時代は終わっていました。

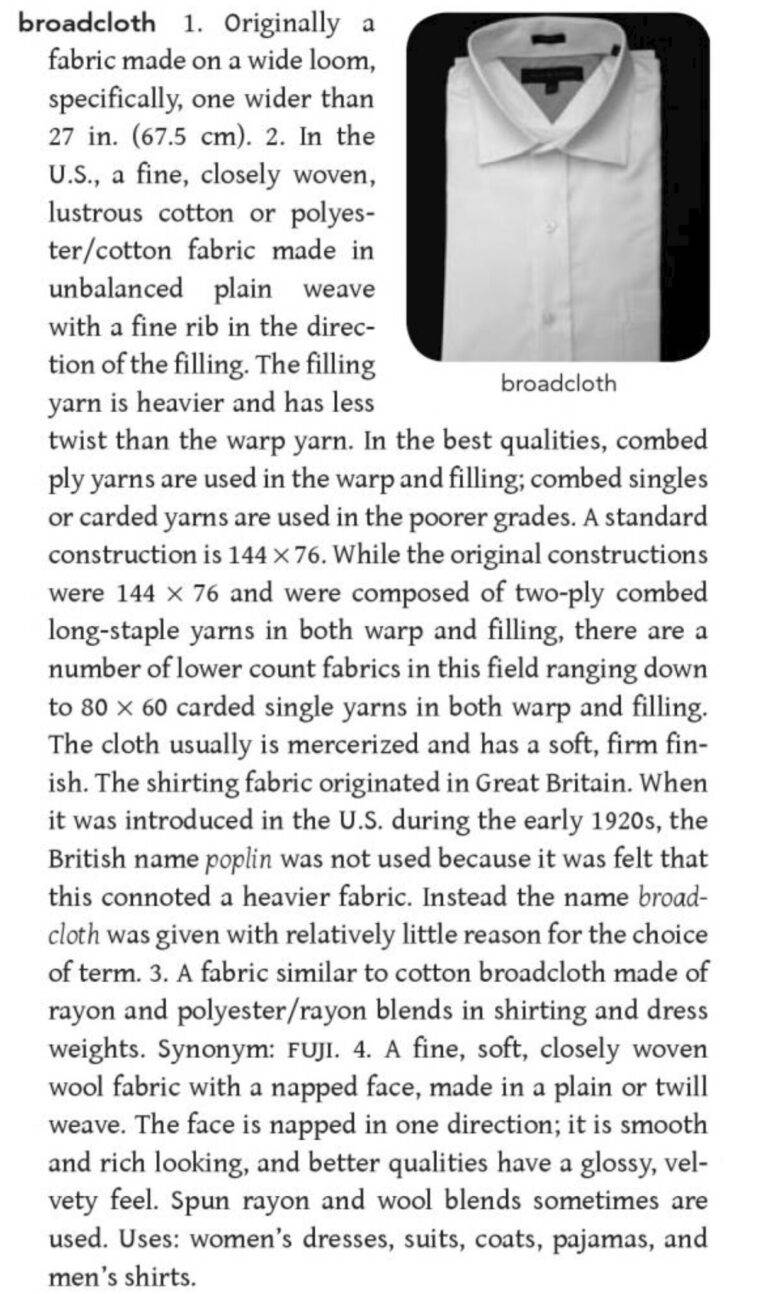

当初、「ブロードクロス」という用語は、「ナロークロス」の対義語としてのみ使われていましたが、後に特定のタイプの布を指す言葉となりました。1909年のウェブスター辞典(1913年に再版されたもの)では、ブロードクロスを「男性の衣類用の、滑らかな表面を持つ上質なウールの布で、通常はダブル幅(つまり、1ヤード半 [140 cm])であり、幅が3/4ヤード [69 cm] のウール素材と区別するためにそう呼ばれる」と定義しており、幅に基づく旧来の区別と、布のタイプに基づく新しい定義の両方を示しています。

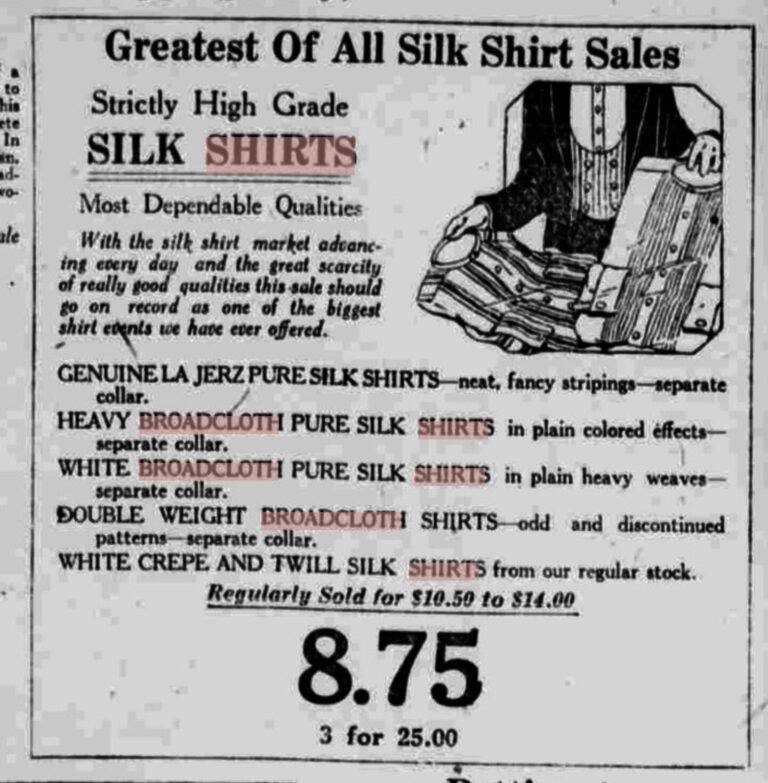

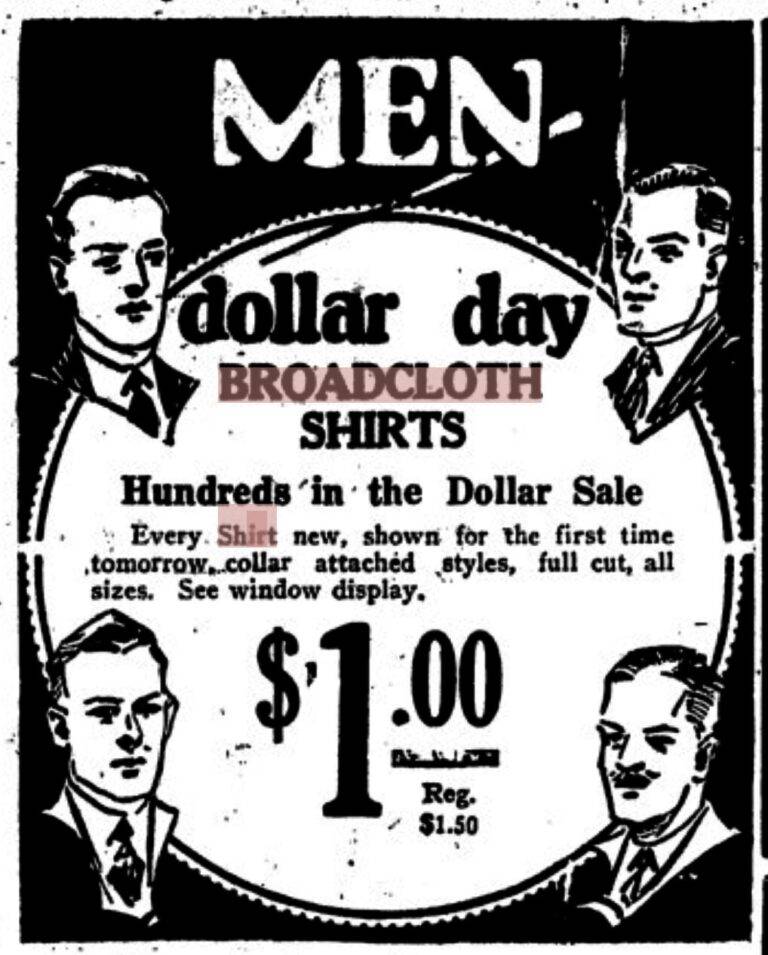

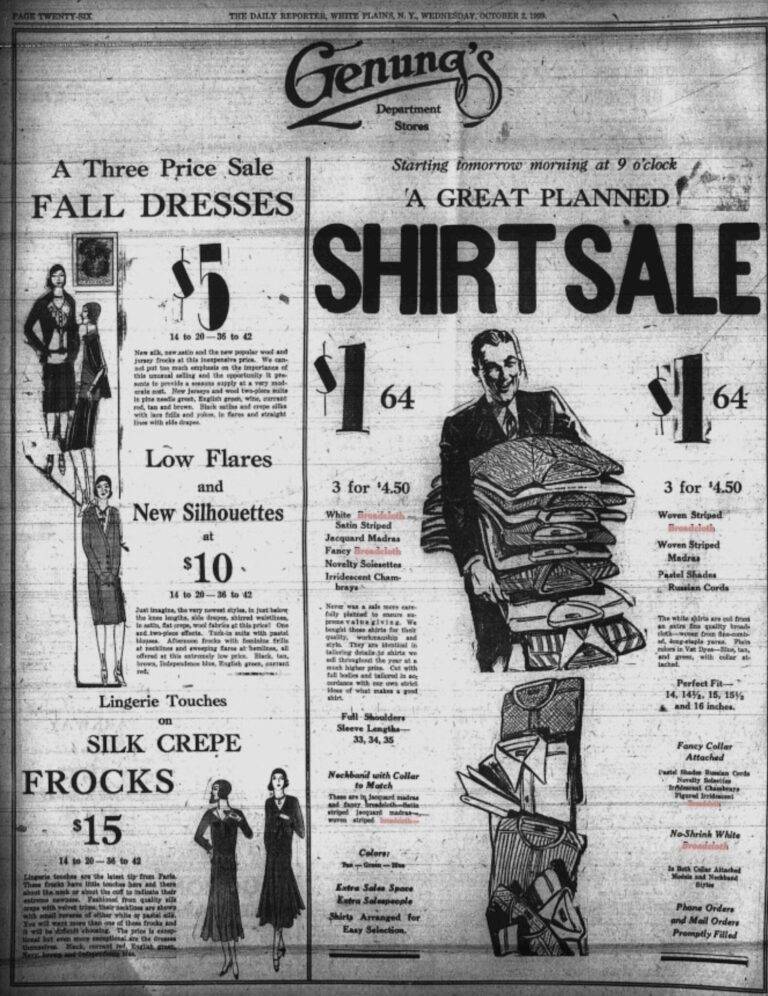

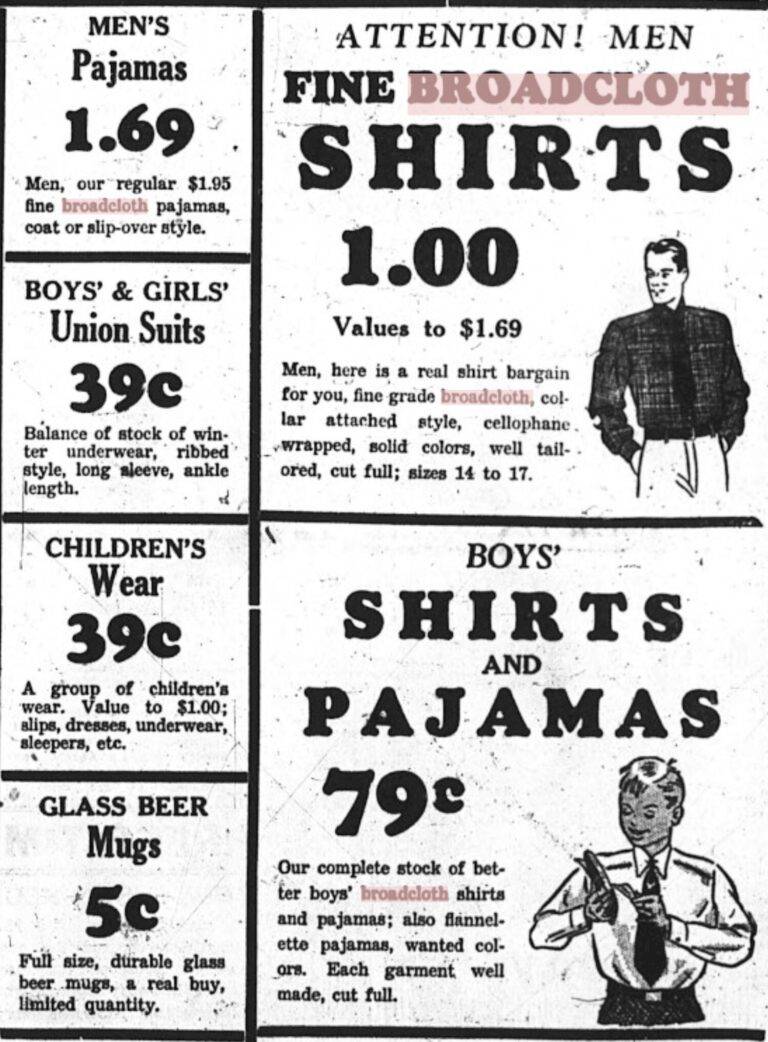

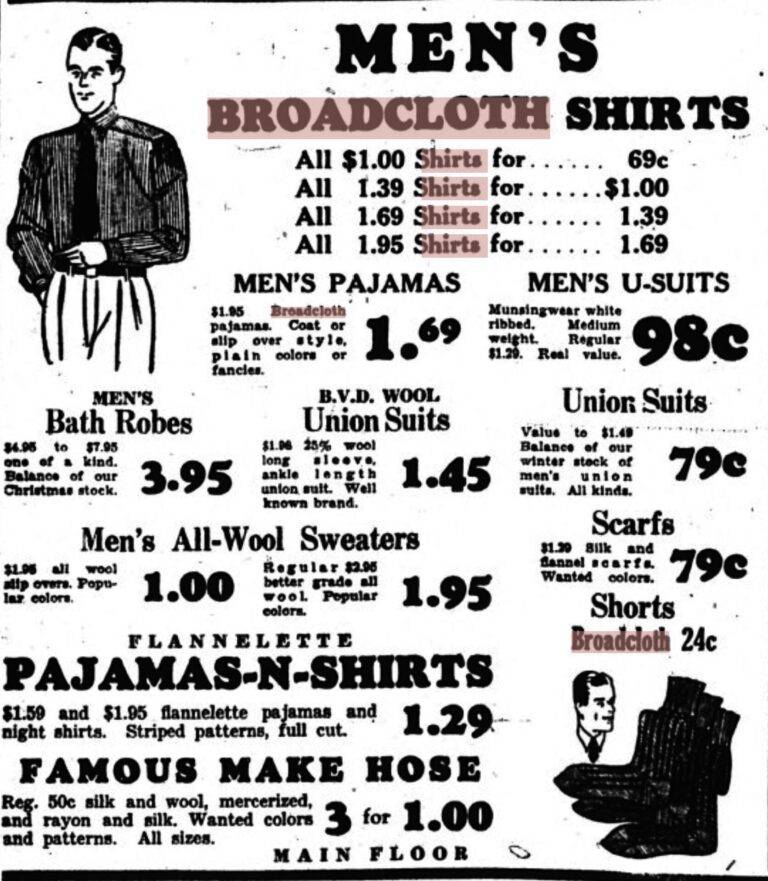

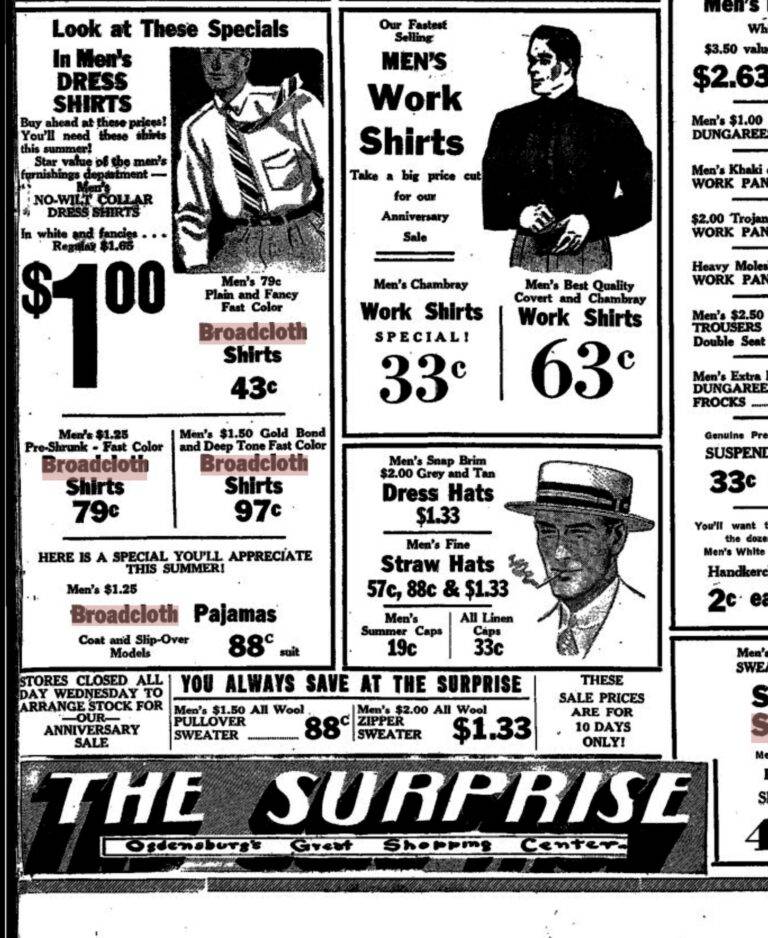

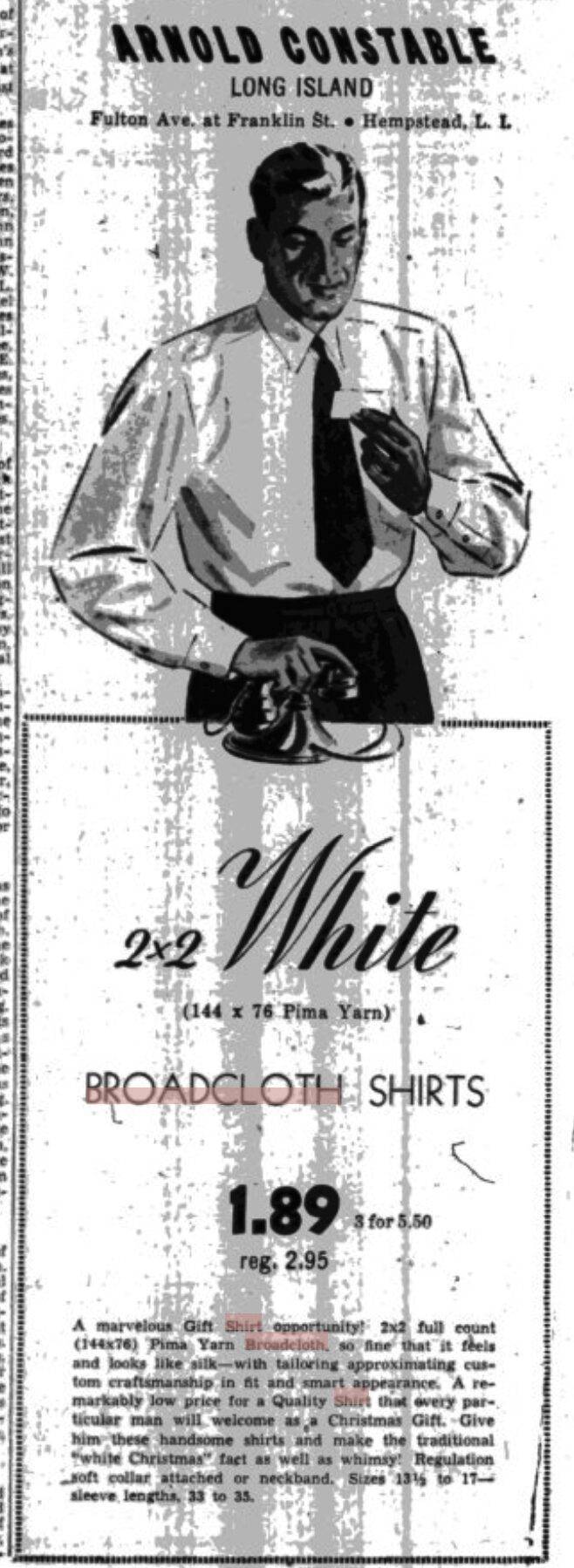

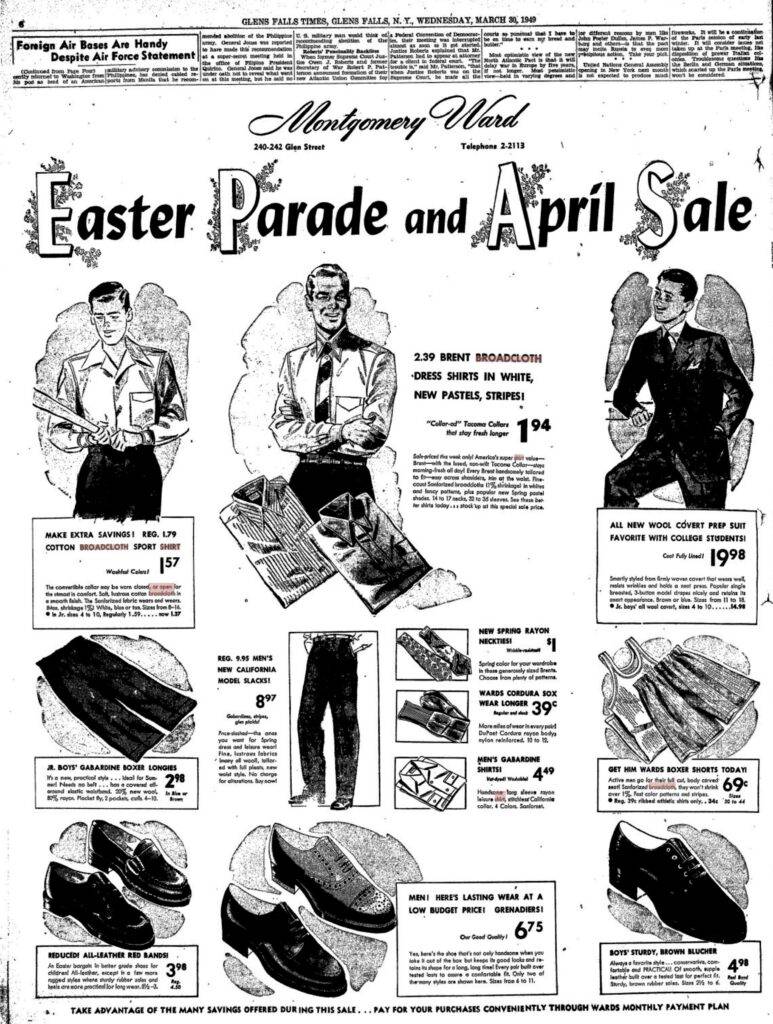

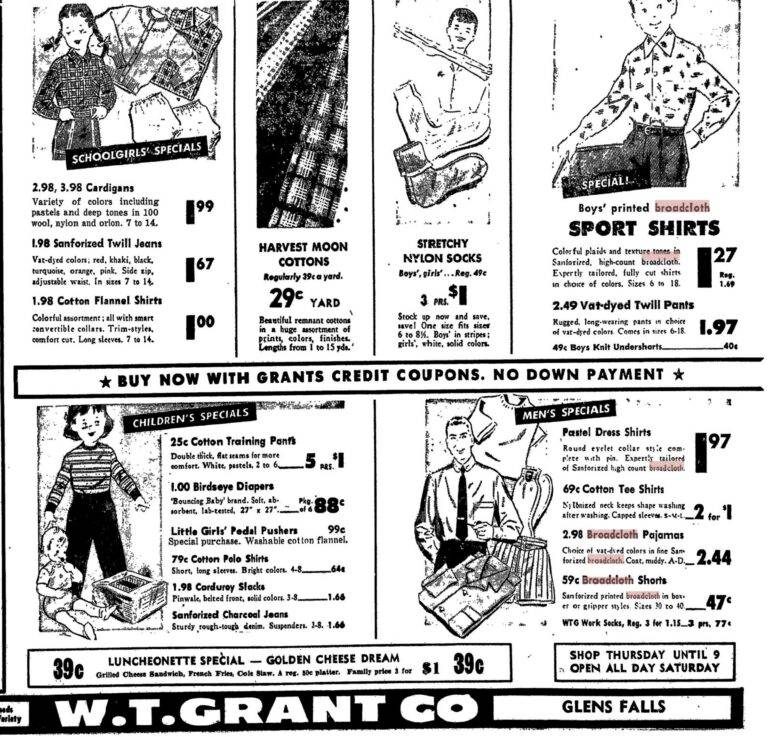

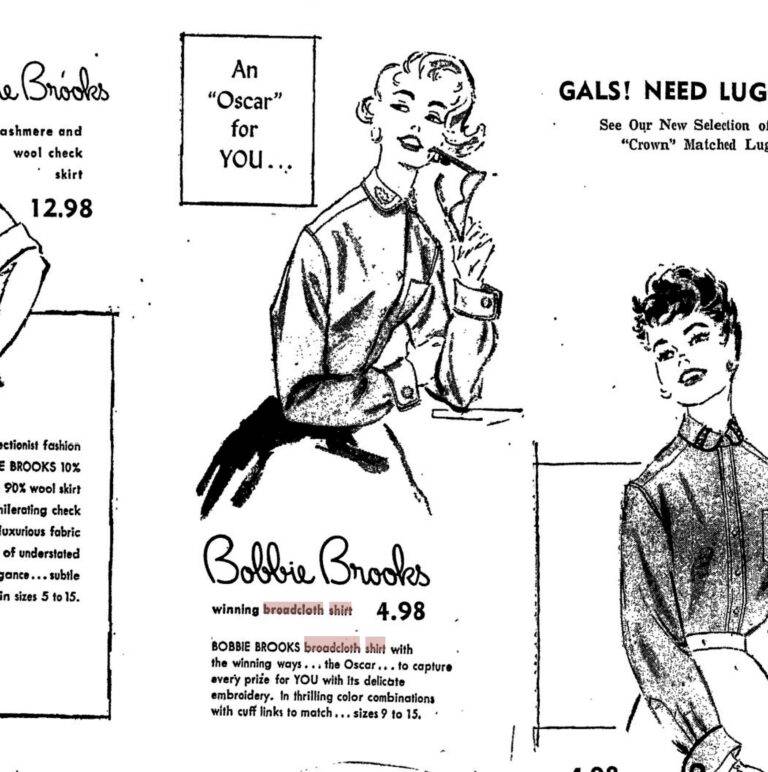

1920年代初頭からアメリカの市場では、「ブロードクロス」という用語が、平織りで通常はマーセライズ加工(シルキー加工の一種で、綿糸または綿布にシルクのような光沢を持たせる加工。 別名シルケット加工)された布を指す言葉として使われるようになりました。この布は、綿またはポリエステルと綿のブレンドから作られ、リブ(畝)のような風合いと密度の高い緯糸が使用されており主にシャツ作りに使われます。この生地は1920年代初頭にイギリスからの輸入品として導入されましたが、そこではポプリンと呼ばれていましたが、ポプリンが重量感を連想させると考えられたため、恣意的に「ブロードクロス」と改名されました。

米国の関税率表(Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States)では、以下のように分類されている。「ブロードウーブン」と「ナローウーブン」という明確な用語を使用しており、幅のカットオフは30センチメートル(約12インチ)です。この定義によると、アメリカ政府は、重量に基づいて全世界の布生産の約70-75%がブロードウーブンであると推定しています。

ジェームス・マクリーリー&カンパニー 5番街 木曜日に 34番ストリート

特別セール 2700枚 メンズ シルクシャツ $7.95 (税込)

明日は、良質なコットンシャツに少し上乗せした価格で、より良い種類のシルクシャツがセールに出される開始日です!これらは、重量のあるブロードクロスシルク、全シルクの白いジャージー、白い自己縞の入ったシルククレープ、カラーストライプのシルククレープといった、耐久性に優れた信頼できる素材で作られています。保守的な色合いと大胆な色合い・デザインの両方があります。多くの場合、7.95ドルでは実際の素材の価値をカバーしきれません!

Cotton is a fabulous fibre !

The history of sheep breeding.