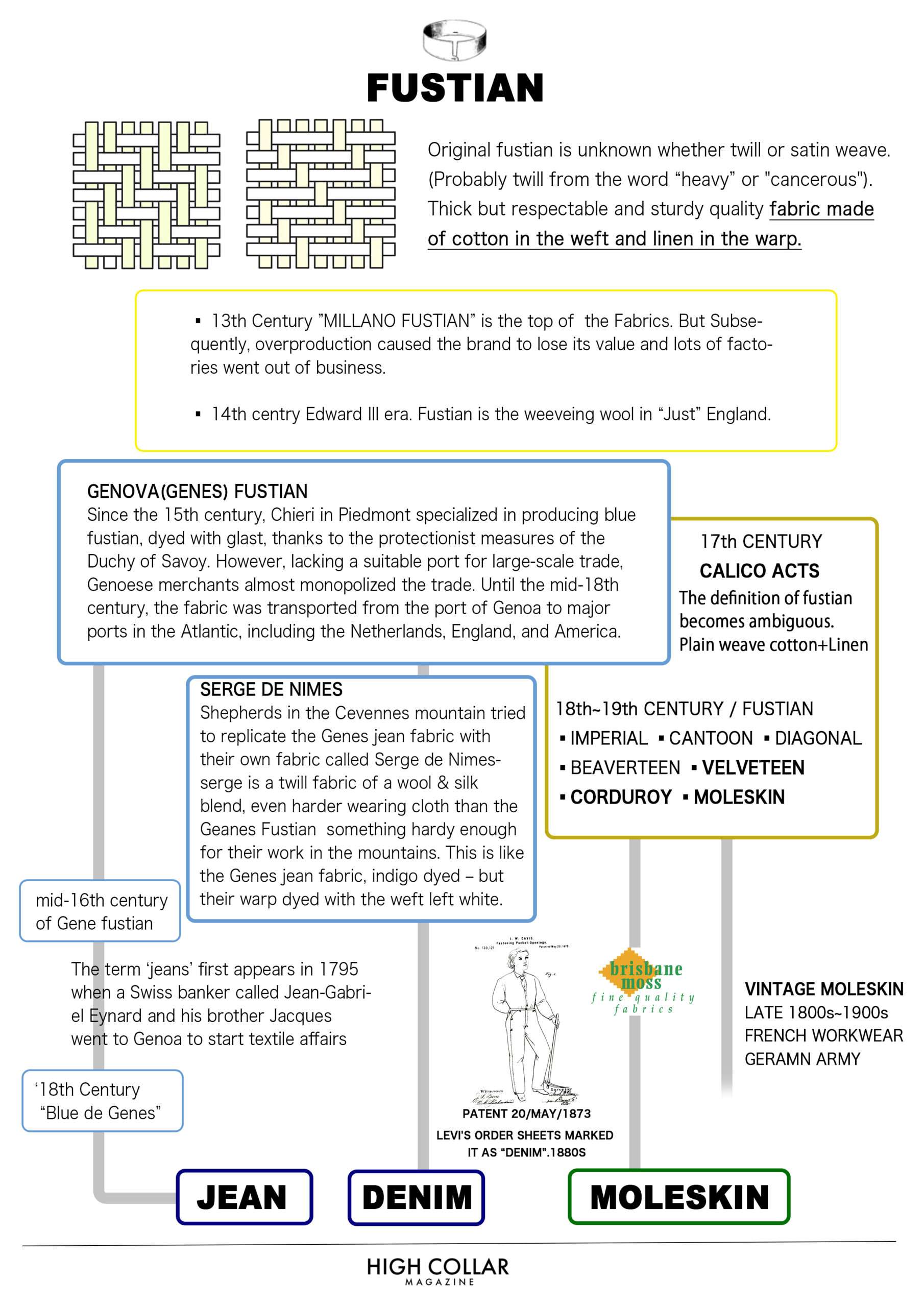

FUSTIAN

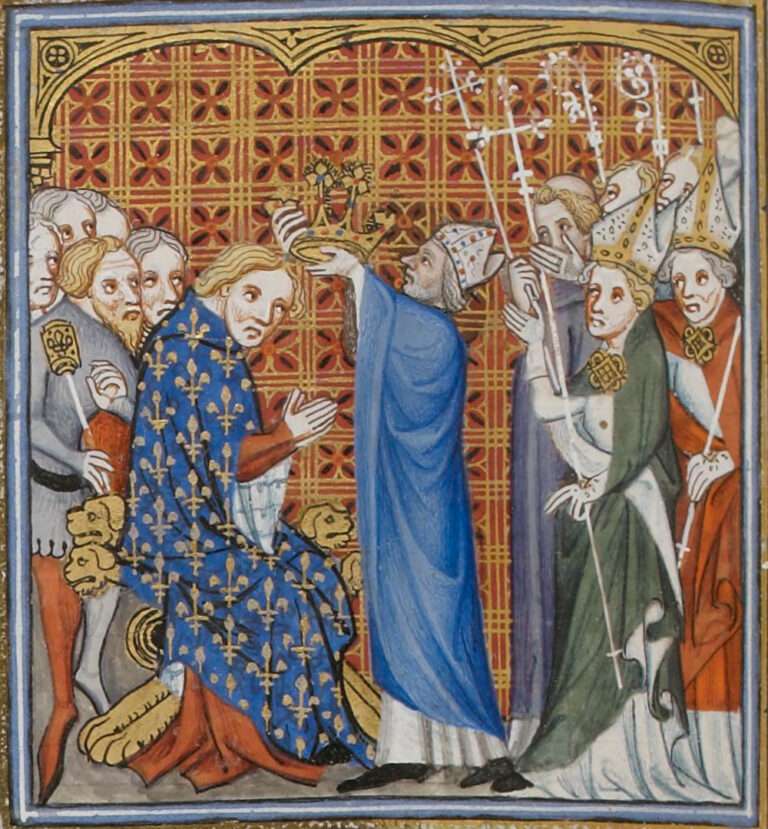

イングランドでは、エドワード3世の時代、フスティアンは綿織物だけでなくウール織物も指していました(英国がウールの産地だったのもあります)。メアリー1世の治世にイギリス議会に提出された請願書には、「ナポリのフスタニー」と記されています。13世紀から14世紀にかけて、司祭の習慣や女性のドレスはフスティアンで作られ、それが現在まで作られています。また頑丈なフスティアンは主に作業着に使われていました。産業革命によりこの生地の生産に特殊な機械が導入されより完璧な仕上がりと低価格が実現します。イギリスのランカシャー地方はフスティアンの生産に特化し、やがてグレーター・マンチェスターが市場をリードするようになります。その他の生産地としては、チェシャー州のコングルトン市、スタフォードシャー州のモウ・コップ、ウェスト・ヨークシャー州のヘプトン・ストールなどがありました。1800年から1850年にかけては、オーストラリアでも広く販売され、”バラガン・フスティアン “として知られた。20世紀初頭には、さまざまな色に染められたコットン製のフスティアンが流行しました。

FUSTIAN = 伊 Fustagno

there are two versions regarding the etymon. The first wants the name to derive from the Arab village of al-Fustāt, a suburb of Cairo in Egypt, from where this fabric was originally imported; the second believes the etymon to be much older and that it goes back to the Latin fustis = stem, referring to the medieval lana de ligno = wood wool from which fustaneum = from the stem was derived. There is also the word fushtan, which referred to a heavy cotton-based type of cloth.

◾️ オリジナルフスティアン / 頑丈な布 / 綿糸の緯糸と亜麻糸の緯糸です。

◾️ その後のフスティアン / コットンの輸入により安価で粗悪なものが混入しだす。

◾️ その後のフスティアン / 頑丈な布 / 羊毛または粗い亜麻織物など定義が曖昧になる。

◾️ 14世紀のフスティアン / 頑丈な布 / 英国ではほぼ羊毛。

◾️ 前近代のフスティアン / 平織または斜織 / 綿と亜麻の混紡(キャリコのようなもの)です。

フスティアンは、紀元前1200年頃に「厚手の布」として生まれました。この用語は古フランス語のfustaigne、fustagne(12世紀、現代フランス語ではfutaine)に由来し、中世ラテン語のfustaneumからの可能性もあります。ラテン語のfustisは「棒、木の棒;棍棒、こん棒」を意味し、ギリシャ語のxylina lina「木のリネン(綿)」(つまり「綿」)の借用翻訳と考えられます。しかしながら、中世ラテン語の語源がエジプトのカイロ近郊に位置するフォスタート(Fostat)とされることもあります。[Kleinはこの語源説を支持していないと述べています。] 1590年代には比喩的な意味で「誇張した、短気な言葉遣い」として用いられるようになりました。

fustigate(動詞)は1650年代に登場し、「こん棒で打つ、打撃する」という意味を持ちます。この用語はFustication(1560年代)から後退派生した可能性があるか、またはラテン語のfusticatus(過去分詞)から派生したと考えられます。fusticareは「(致命的にまで)こん棒で打つ」を意味し、fustisは「こん棒、棍棒、棒、木の棒」という意味で、起源は不明です。De Vaanによれば、「最も明らかな関連はラテン語のfutare」とのことですが、「進化上の困難がある」とされています。この用語は1650年代から使われ続けています。

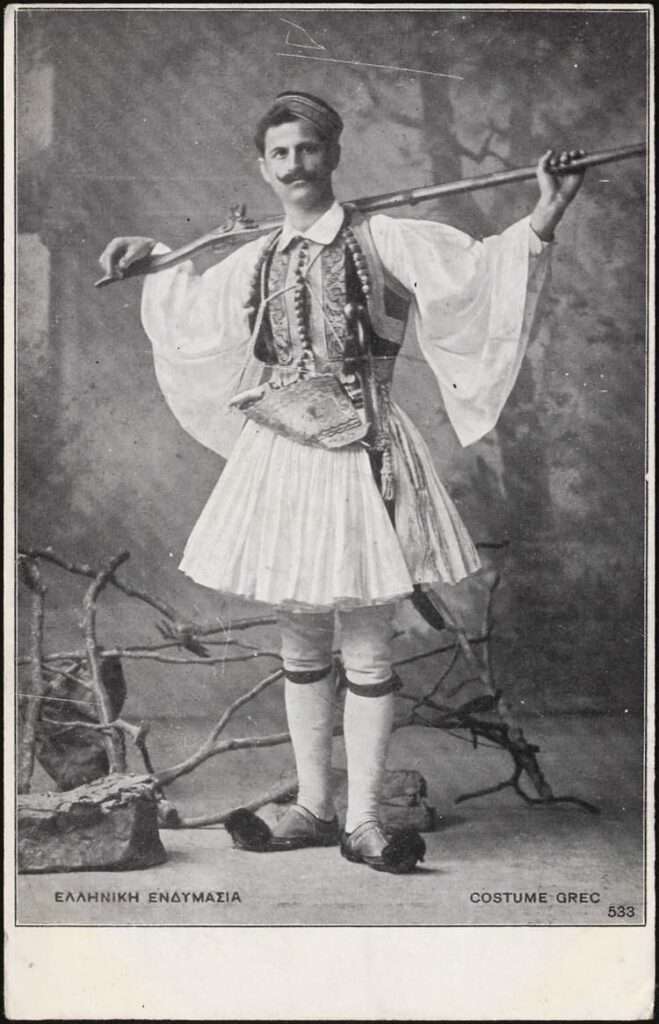

フスタネラの語源は、イタリア語のfustagno「フスティアン」と-ella(短縮形)である。これは中世ラテン語のfūstāneumに由来し、おそらくfustis「木のバトン」の短縮形であろうと予測されます。他の著者は、これをギリシャ語のキシリーノ(ξύλινο)、文字通り「木製の」、すなわち「木綿」の訛りとも考えています。また、布が製造されていたカイロ郊外のフォスタットに由来するという者もいます。この衣服は、アルバニア人のサブグループであるチャムスの民族名にちなんだtsamika/çamikaや、klephtsとして知られる山賊にちなんだkleftikiなど、他の呼び名でも知られています。

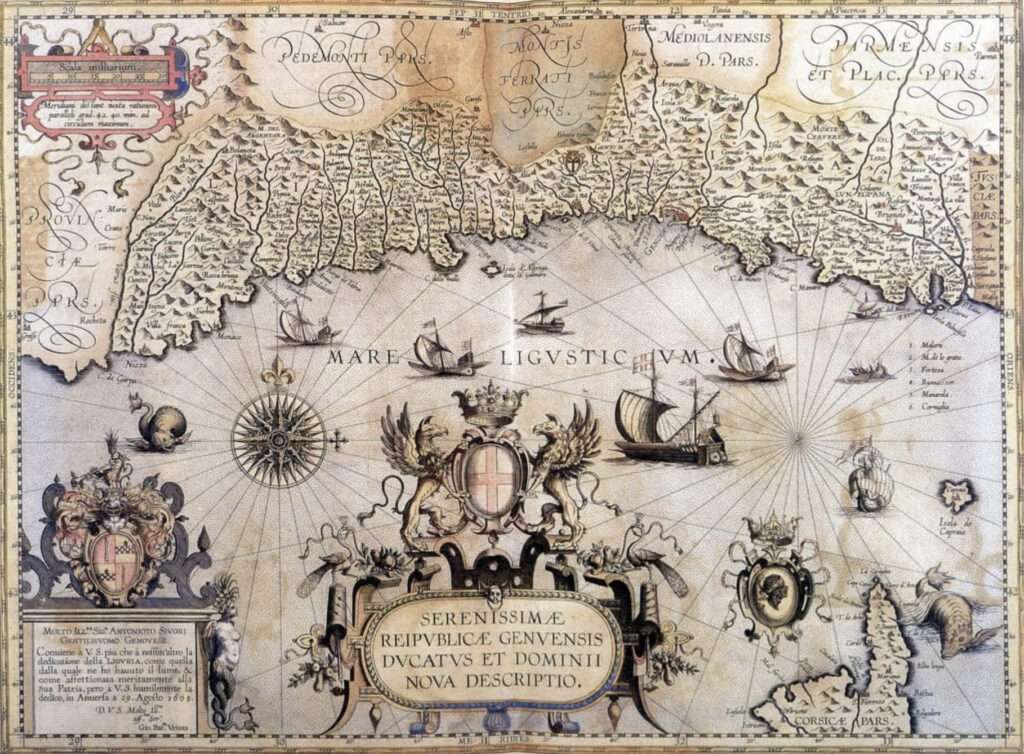

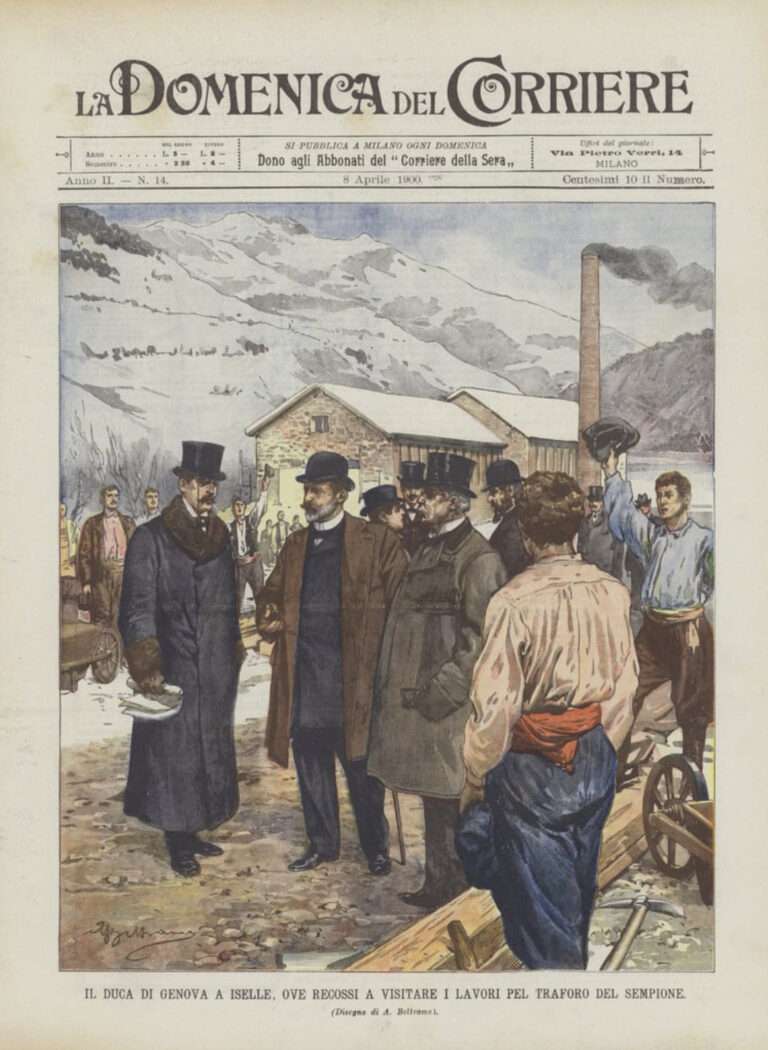

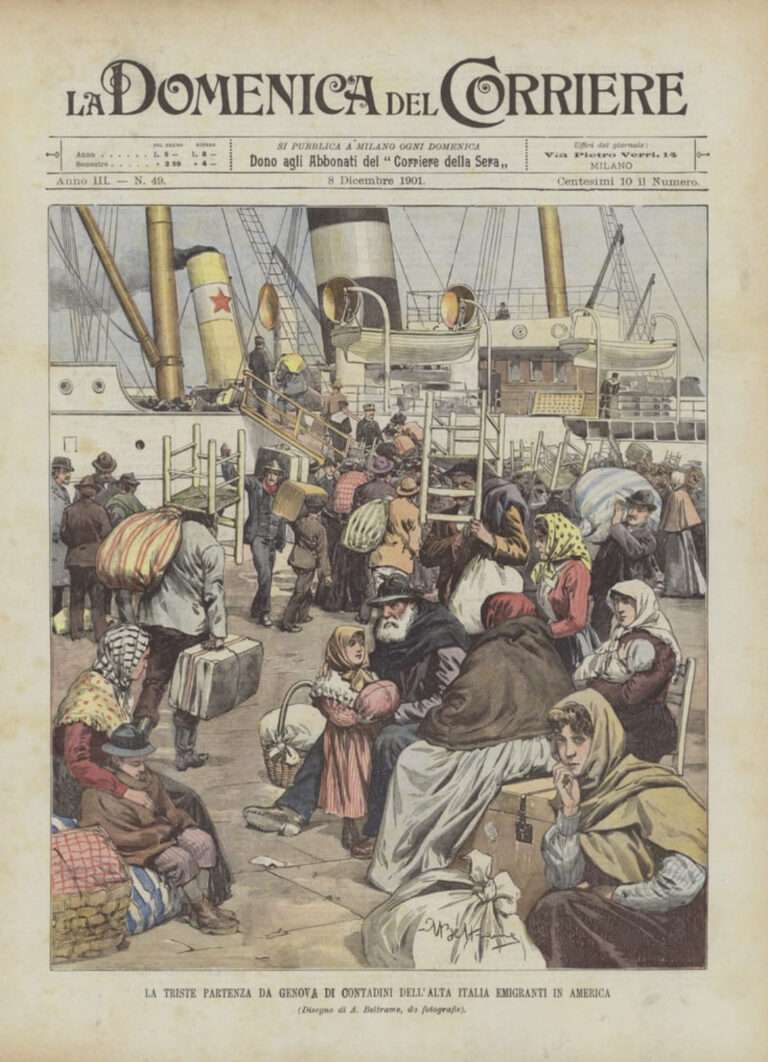

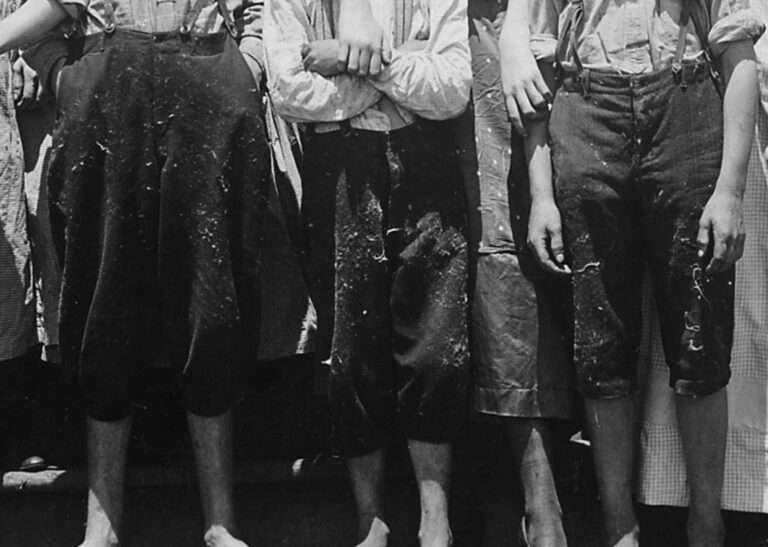

1775年12月28日、フランスのリヨンに生まれたジャン=ガブリエル・エイナールは、スイスの銀行家です。父のガブリエル=アントワーヌ・エイナールは旧華族の出身で、銀行家、商人として働いていました。1793年、フランス革命が過激化する中でエイナール一家はスイスのロールに移住したます。1795年、ジャン=ガブリエルと弟のジャック・エイナールはジェノヴァに居を構え商会を設立した。特筆すべきは1801年、エイナールが当時のエトルリア国王に代わって融資を受けリヴォルノで大きな財を成したことです。3年後、銀行業を引退しフィレンツェで公職に就いた。1808年にはロール市民となり、スイス国籍を取得します。

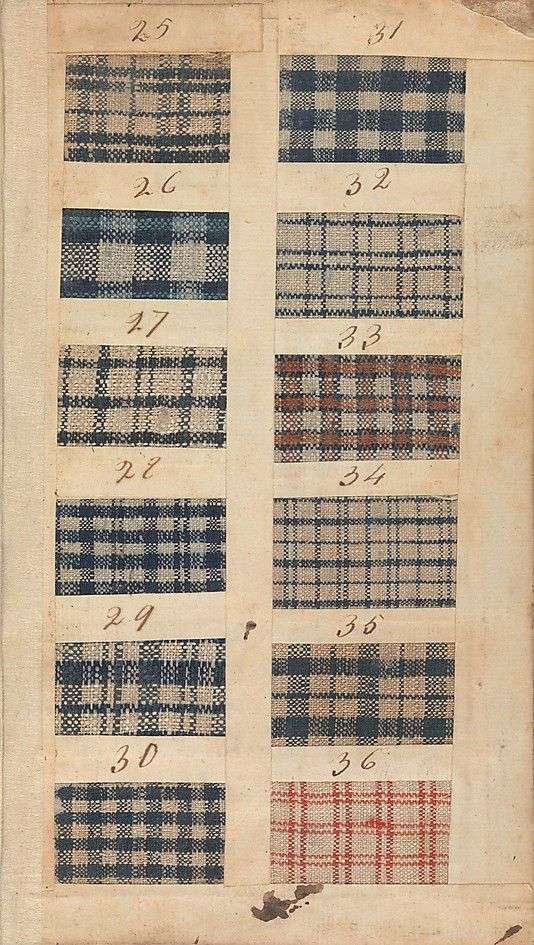

1795年、2人の兄弟は商会を開き、その中であのフスティアンに注目しました。彼らが最初に「BULE de GENES」と名付けたと言われている。そしてそのフスティアンの事業は大成功を収めることになります。

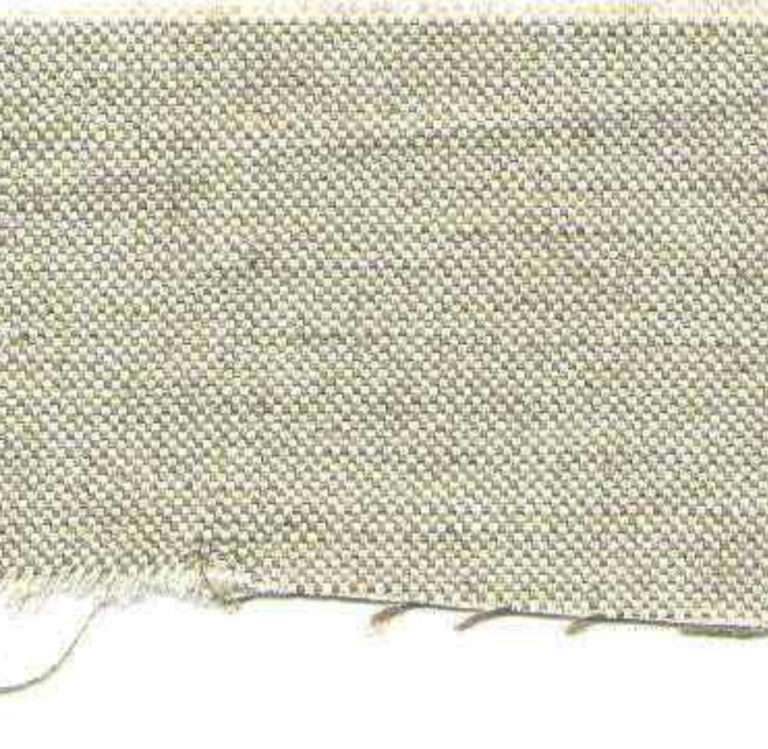

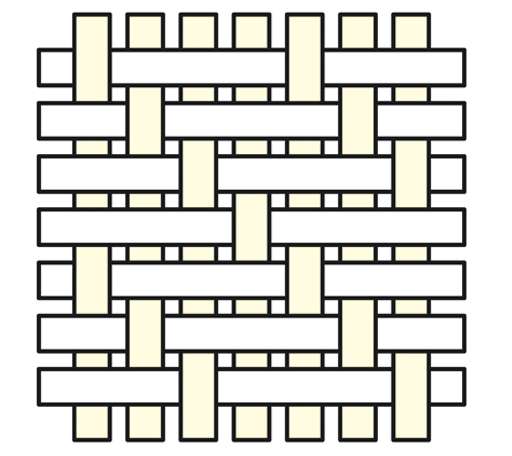

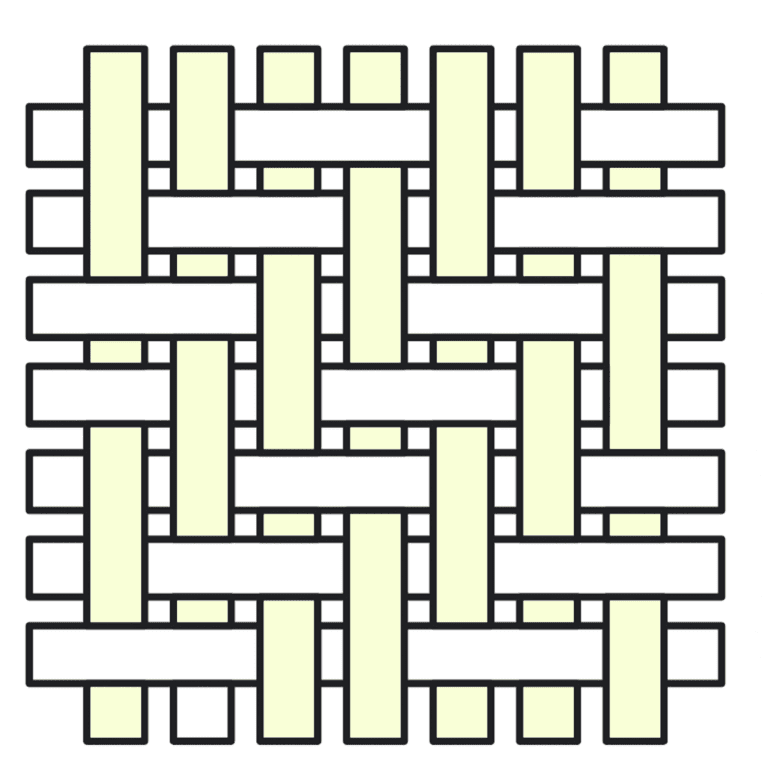

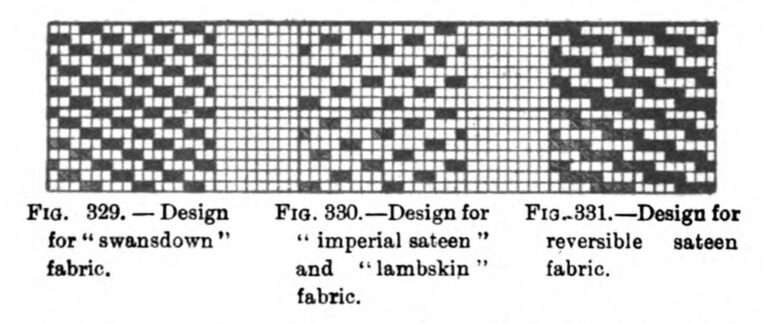

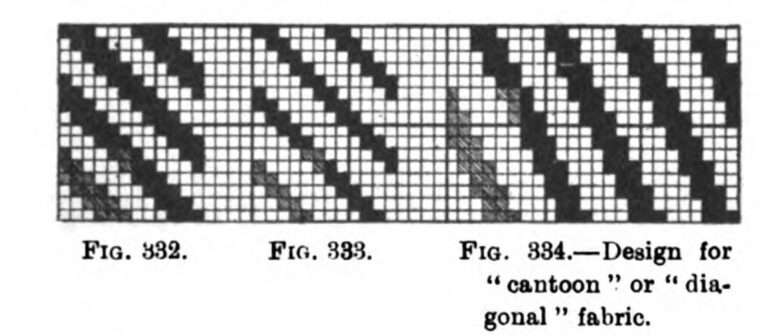

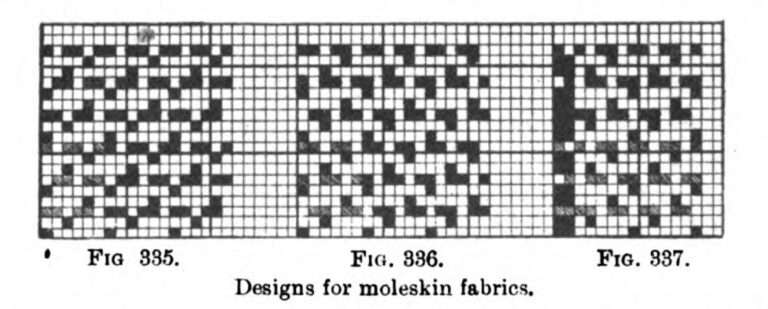

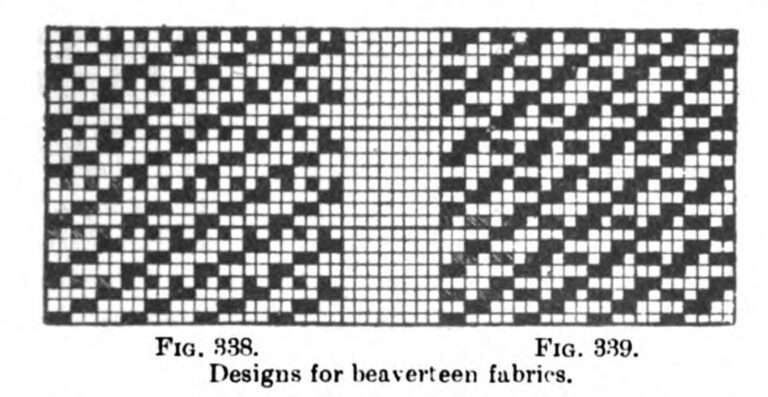

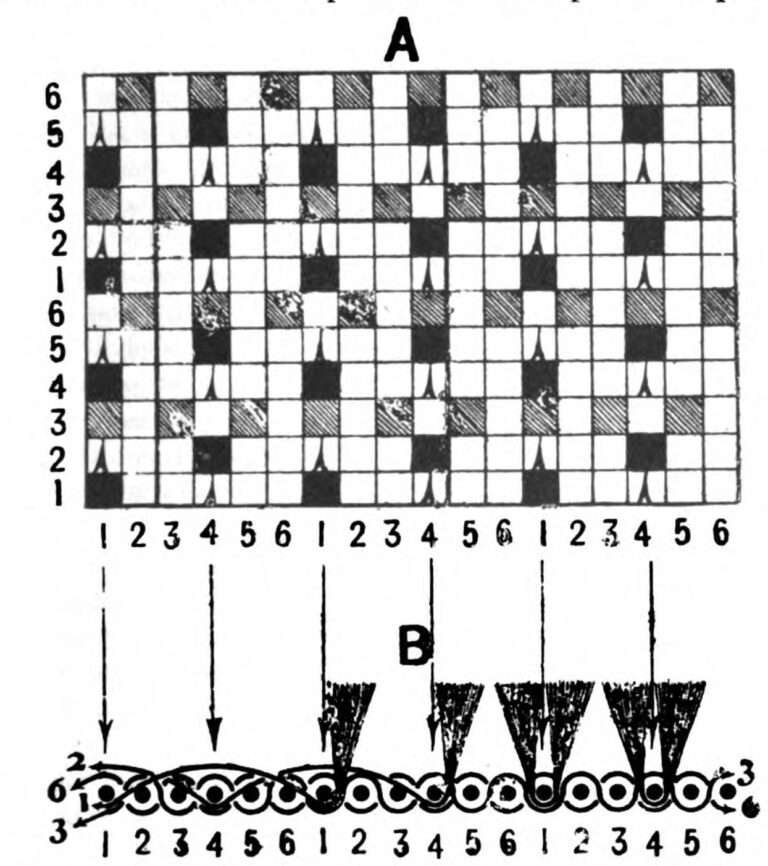

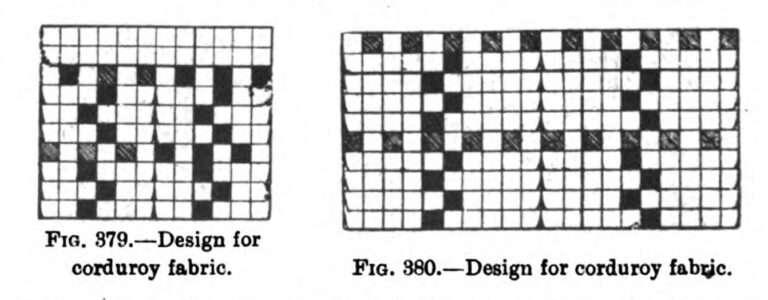

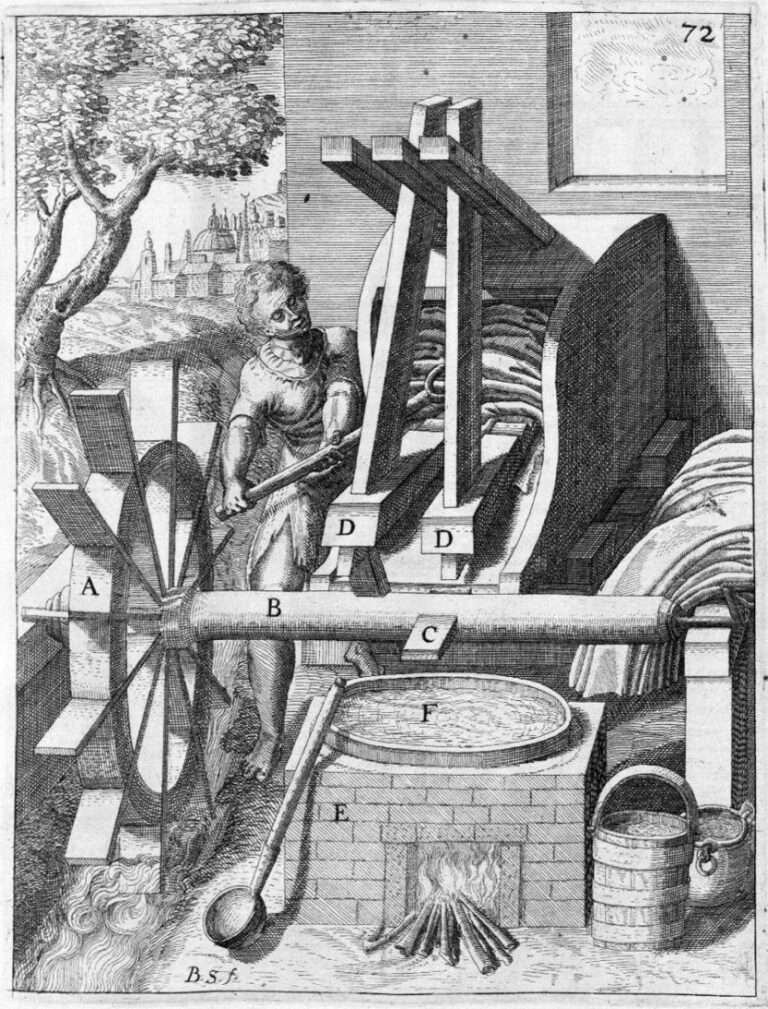

Fustians are a well – known type of cotton fabrics com prising several varieties , the chief of which are known as “ imperial , ” ” swansdown , ” ” cantoon , ” or “ diagonal , ” “ mole skin , ” “ beaverteen , ” ” velveteen ” or cotton velvet formed with a weft pile , and ” corduroy ” . With the exception of velveteens , which simulate the real silk velvet formed with a warp pile , they are comparatively firm , heavy and compact textures of great strength and durability , chiefly employed in the produc tion of clothing . The first three varieties embody no special constructive feature in their design , as they are based on some simple weave that permits of an abnormally high rate of picks being inserted so as to produce a compact fabric . Each of the remaining varieties , however , is characterised by some peculiar constructive element that distinguishes it from all other fabrics . These are virtually “ backed ” fabrics , since they are constructed from one series of warp threads and two series of weft threads , namely , “ face ” and ” back ” picks , although both series of picks are of the same kind of weft , thereby requiring for their produc tion a loom with only one shuttle – box at each end of the sley .

However, with the decline of the British textile industry since the 1920s, the industrial buildings have been abandoned and now face demolition.

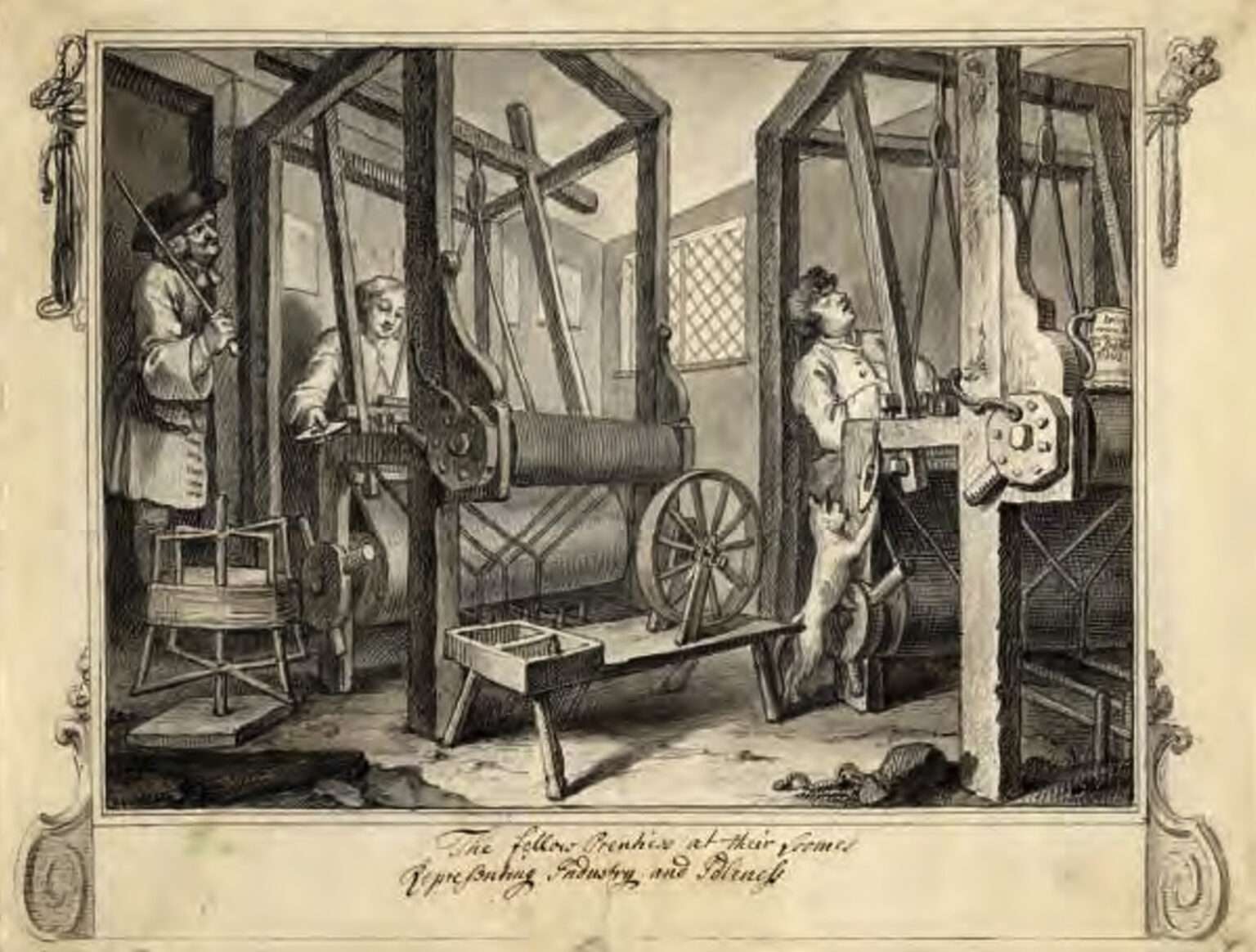

「テキスタイルミルズ=繊維工場」というシステムは、天然繊維を原材料の加工から糸の紡績、糸を織る製織、漂白、染色、そして印刷までのすべての行う工場のことを意味します。産業革命が勃興し繊維業界に大量の資本が流れてくると、この「テキスタイルミルズ」に多くの投資や新工場の設立のブームが湧き起こります。ウールをはじめリネン・シルクなどの繊維は英国の産業においても中世から重要な産業でしたが、18世紀に入りここランカシャーでは繊維を製造に携わる機械・スチームエンジン・ボイラー・工場建設のための鉄の梁や柱、機械部品を製造する専門のエンジニアリング会社などが次々と誕生していきました。そして産業革命は英国を世界の覇者にまで君臨させることになります。しかしその後他国の産業革命も始まり、また自由の国アメリカの存在感が徐々に増していき、二つの大戦を挟んで、賑わっていたランカシャーの街もバツ楽の道を歩み始めます。20世紀中盤より製糸工場の基盤をベース人口繊維へとシフトしていきますが、その過程でスケルマースデールにあるコートールズ・コンプレックスのような巨大な繊維工場が設立されました。このようにランカシャーの織物工場は、地域の経済、人口、建築の形成に重要な役割を果たしました。19世紀後半には、ランカシャーは総人口400万人のうち50万人以上を綿織物の生産に従事させ、世界最大の綿花産業を有していたため、マンチェスターは「コットンポリス」というニックネームで世界的に有名な産業都市となりました。ランカシャーは世界の綿製品の30%以上を供給し、国の輸出の半分以上を占めていました。この地域は18世紀と19世紀に産業革命を推進するいくつもの発明を行ったため技術革新の源泉ともなりました。しかしながら、1920年代以降の英国の繊維産業の衰退により、これらの産業用建物は放棄され、取り壊しの危機に直面しています。

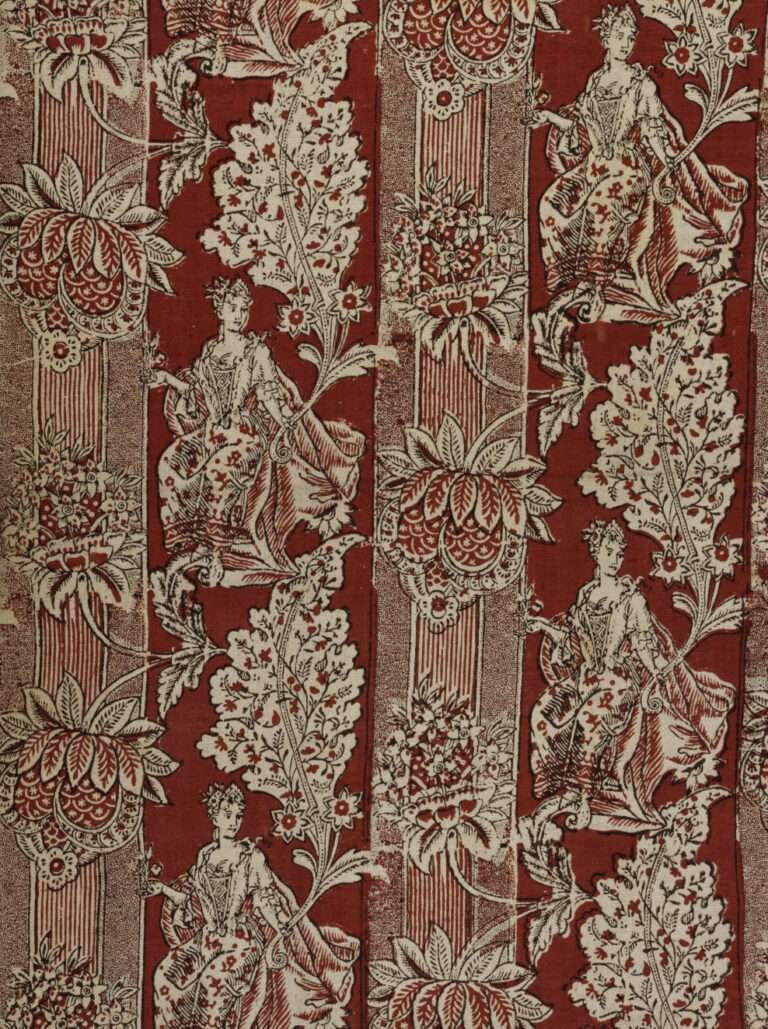

- 1685: Introduced a 10% tariff on the import of East Indian goods.

- 1690: Passed “The Impost of 1690” imposing a 20% tariff on the import of East Indian goods, wrought silk, and other foreign commodities.

- 1700: An act aimed at encouraging domestic manufacturers by banning most imports.

- Prohibited the use and wear of certain imported goods, including wrought silks, Bengals, and stuffs from Persia, China, or East India, and printed calicoes.

- Required these prohibited goods to be locked up in customs-appointed warehouses until re-exported, imposing a penalty of £200 for possessing or selling them.

- Imposed a 15% duty on Muslins and a duty on East India Goods.

- Abolished the export duty on English woolen produce.

- 1707: Implemented a 50% tariff on Indian goods.

- 1721: Enacted the Calico Act, which banned the sale of most cotton textiles.

- Prohibited the use and wear of printed, painted, stained, or dyed calicoes in apparel, household stuff, furniture, or any other way after December 25, 1722.

- 1730s: Modified the Calico Act to allow the sale of British printed fabrics, providing an exemption.

- 1774: The Calico Act was repealed, leading to a wave of investments in mill-based cotton spinning and production. This resulted in an increase in the demand for raw cotton, which continued to grow significantly over the years.

以下は一連の関連する法律です:

- 1685年:東インド製品の輸入に10%の関税導入。

- 1690年:東インド製品、絹織物、その他の外国産品の輸入に20%の関税導入する「1690年不敬罪」を可決。

- 1700年:国内の製造業者を奨励するためほとんどの輸入を禁止する法律。ペルシャ、中国、東インド産の絹織物、ベンガル織物、プリント更紗など、特定の輸入品の使用と着用を禁止し、これらの品物は再輸出されるまで税関指定の倉庫に保管され、所持または販売には200ポンドの罰金が課せられました。一方、ムスリンに15%の関税が課され、東インド商品には関税が導入されました。また、イギリスの毛織物に対する輸出関税は廃止されました。

- 1707年:インド製品に50%の関税が課せられました。

- 1721年:キャリコ法が制定され、ほとんどの綿織物の販売が禁止されました。1722年12月25日以降は、衣服、家庭用品、家具などあらゆる形態でのプリント、ペイント、染色、染色のキャリコの使用と着用が禁止されました。

- 1730年代:キャリコ法が修正され、英国製プリント生地の販売が許可されました。免除規定が設けられました。

- 1774年:キャリコ法が廃止され、工場での綿花紡績と生産への投資が増加しました。原綿の需要が増加し、綿花産業はその後も大きく発展していきました。

The world's best cotton has disappeared

The muslin fabric featured in Marie-Antoinette’s portraits. The sheer, transparent fabric fascinated European aristocrats. And the lost world best beautiful fabric “Dhaka Muslin” from Mughal Empire (Now Bangladesh) , They can no longer be reproduced. The craftsmen who made the delicate fabric had their fingers chopped off by the British man.