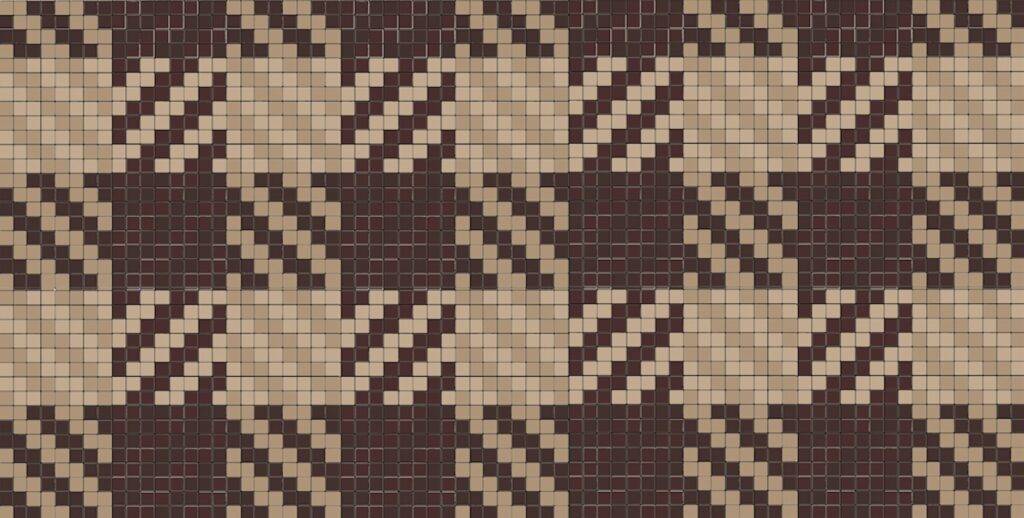

Diodorus Siculus notes that the Gauls had a preference for multi-colored check patterns, while the Romans in Italy viewed tartans with a degree of mistrust. Expanding on this, Pliny suggests that it was the Gauls who originally created these designs (referenced in Diodorus, V.30.I; Pliny, N.H.VIII.196). In Latin, these woolen tartans were known as “scutulata.”

“Scutulata” is a term in Latin relating to textiles and fabrics. Used during the ancient Roman era, this word specifically referred to woolen tartans (fabrics) with checkered or grid-like patterns. The term “Scutulata” is derived from “scutulum,” which means ‘small shield’ or ‘fragment,’ suggesting that it referred to specific design elements in the fabric, namely small divisions of color or patterns in the weave. This term reflects cultural and historical aspects of ancient weaving techniques and designs.

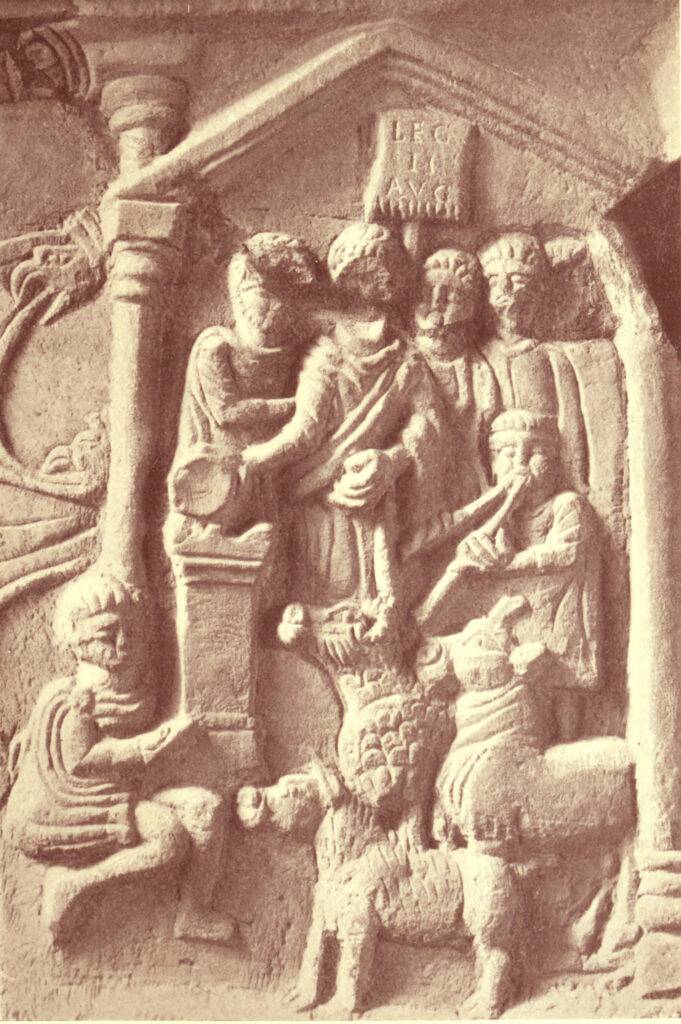

The primary garment in Roman Britain was known as the ‘Gallic coat,’ a loose-fitting tunic that came with or without short, wide sleeves (Wild 2002, 23). For men, it extended to the calves, while for women, it reached their ankles. Existing examples from Northern Europe suggest it was crafted from wool, woven as a single piece on a loom. Men typically wore a large hooded cape over this tunic, shaped like a circle segment, whereas women wore a simple, rectangular cloak. Soldiers also donned rectangular cloaks, draped around the shoulders and secured with a brooch on the right shoulder. These garments, among others, are referenced in the Vindolanda tablets. The piece of cloth used to protect the Bellsmeadow coin hoard might have been from such a cloak, though this remains uncertain. The Falkirk tartan, according to Ryder’s fiber analysis, likely wasn’t produced locally. It contained fine (white) wool, possibly from gray animals introduced by the Romans, resembling but superior to the Soay sheep of Scotland. Sheep were definitely around in Falkirk during that period, evidenced by sheep hoof prints on a Roman tile from the Camelon fort. Notably, a sheep was one of the three animals sacrificed in the souvetaurilia ceremony, believed to celebrate the completion of the Antonine Wall’s construction, as depicted on the Bridgeness Tablet.

ディオドロス・シクルスは、ガリア人が多色のチェック柄を好んでいたことを指摘していますが、イタリアのローマ人はタータンに対してある程度の不信感を持っていました。これをさらに発展させて、プリニウスはこれらのデザインを最初に作り出したのはガリア人だったと提案しています(ディオドロスの記述、V.30.I; プリニウス、N.H.VIII.196にて言及)。ラテン語では、これらのウールのタータンは「スクツラータ」として知られていました。

「Scutulata」は、ラテン語で織物や布地に関する用語です。古代ローマ時代に使用されたこの言葉は、特に格子状の模様やチェック柄を持つウールのタータン(布地)を指していました。”Scutulata”という言葉は、「小さな盾」や「小片」を意味する「scutulum」から派生しており、これは布地の特定のデザイン要素、つまり織りにおける小さな色の区分やパターンを指していると考えられます。この用語は、古代の織物技術やデザインに関する文化的および歴史的な側面を反映しています。

ローマン・ブリテンでの主な身体衣服は「ガリック・コート」と呼ばれるもので、短く広い袖があるかないかの広いフィットのチュニックでした(ワイルド 2002, 23)。男性にはふくらはぎまで、女性には足首まで届きました。北ヨーロッパからの現存する例によると、一枚の布で織られた羊毛で作られていたことが示唆されています。このチュニックの上に、男性は大きなフード付きのケープ(平面では円の一部を形成)を、女性はシンプルな長方形のマントを着用していました。兵士たちも長方形のマントを肩に掛け、右肩にブローチで留めていました。これらの衣服は、他のいくつかの衣服と共にヴィンドランダのタブレットに記されています。ベルズメドウのコイン隠しを守るために使われた布片は、このようなマントの一部だった可能性がありますが、確証はありません。ライダーの繊維分析によれば、フォークリック・タータンは地元で作られたものではないと考えられます。それに含まれていた細かい(白い)羊毛は、ローマ人によって導入されたと思われる灰色の動物から来たもので、スコットランドに存在していたソア羊に似ていますが、より良質の毛皮を持っていました。当時のフォークリックには確かに羊が存在しており、カメロン砦のローマンタイルには羊の蹄の跡が見つかっています。アントニヌスの壁の建設完了を祝って行われたと思われるスーヴェタウリリア儀式では、羊が3匹の犠牲動物の一つであり、これはブリッジネスのタブレットに描かれています。

The circumstances of the find

By the late 20th century, Falkirk had expanded significantly, with development extending north and south. In the late 1920s and 1930s, the Town Council initiated a development plan east of Callendar Riggs. This area, including Callendar Riggs and the surrounding land, had experienced extensive sand extraction. The large estates of Rosepark and Bellmont, with their fields, were prime for development. A notable piece of land, known as the Meadow or Bell’s Meadow, stretched between Belmont and the East Burn. In the 1920s, an architecturally notable bus station and new shops designed by JG Callendar appeared along Callendar Riggs, introducing Falkirk’s first suburban shopping center. Falkirk Council then extended a new road, Meadow Street, from the bus station to Market Square. A labor exchange opened on Meadow Street’s north side. Dunn and Wilson set up a bindery nearby, necessitating access from Meadow Street to Kerse Lane, acquired through land from Christ Church. Belmont became offices for the Falkirk Mail and later the Water Board.

In August 1933, John Doak inaugurated a dance hall near the bus station. Concurrently, sand extraction in Bell’s Meadow aimed to flatten the land for bus facility expansion. On August 9, 1933, council workers widening Meadow Street near the Labor Exchange unearthed something unexpected. Worker Robert Wallace initially mistook it for a stone or lead. Recalling wartime treasure discoveries in Greece, Wallace uncovered a vase, which upon removal, broke to reveal many silver coins. A scramble ensued among workers for the scattered coins, but Wallace secured them in a tool shed. The discovery quickly attracted local children and skeptics. The Town Clerk soon took charge of the find.

The next morning, the Town Clerk passed the discovered items to Mr. JG Morrison, the Procurator Fiscal, who then informed the Queen and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer. The coins, pot, and cloth were officially recognized as treasure trove. On August 12th, the Falkirk Herald featured a photo of Wallace holding the pot’s base filled with coins at the sand quarry. Sam Smith, a respected Roman enthusiast from Mumrills, known for archaeological findings on his family farm, visited the discovery site to share insights with experts from Edinburgh. The location was subsequently marked on Ordnance Survey maps, near Meadow Street and close to present-day Bellevue Street. However, Smith, whose opinions were highly regarded, believed the actual site was further west, nearer to Wormit Hill, where Doak’s dance hall (later part of the bus station) stood.

This positioning is supported by earlier area topography and might have influenced Macdonald’s 1934 publication, which described the hoard’s placement at the bottom of a natural hollow or ditch, around 7 feet below the modern surface. Wallace’s photo, taken around midday judging by the shadows, showed him crouching at the quarry’s working level where the pot was found. It seems the hoard was buried in an existing ditch, approximately 6 feet deep and 9 feet wide at the top, likely one of several surrounding Wormit Hill, thought to be a native leader’s center (Bailey 2017). This theory gained further support with a fourth-century copper alloy coin’s discovery in 1957 in another part of Bell’s Meadow (Robertson 1961, 149), not part of the hoard but indicating continued local habitation.

The coins were sent to the National Museum of Antiquities in Edinburgh, where Sir George Macdonald examined them after returning from a holiday in Switzerland. It was discovered that the collection comprised 1930 coins, weighing approximately 2.0g each, totaling around 3.860kg. Wallace, seeking a reward, hired local solicitor Thomas Cassells to navigate the Treasure Trove system. Initially offered £25, he appealed for more, arguing for a bullion value based on the intrinsic worth of the coins, which was about 3d each. This request for a reward sparked controversy among locals, leading to debates in newspapers. Meanwhile, a dispute arose as some of Wallace’s colleagues kept individual coins as souvenirs, a practice deemed illegal. On October 3rd, D.K. Paterson, Honorary Curator of the Falkirk Museum in Dollar Park, requested these coins be returned, promising no legal action. This appeal yielded three coins from Wallace and one from an anonymous donor, with another added in 1963.

The cloth found with the coins is briefly mentioned in early reports, but it is crucial in dating the Falkirk tartan. The most recent coin, minted for Alexander Severus in 230AD, was worn, suggesting the hoard’s burial shortly after 240AD. The coins are believed to have been a Roman ‘subsidy’ (bribe) to a local leader for cooperation. Despite the focus on the coins and the pot’s collapse upon removal, the survival of the tartan is fortunate. The coins only half-filled the pot, implying the cloth was placed on top, likely larger initially but mostly decayed over time. Alternatively, it might have been a small piece laid over the coins. A similar hoard in Birnie, Moray, contained two leather pouches of coins in one of its ceramic vessels, suggesting the possibility of multiple payments over time.

The second vessel from the Birnie site also contained leather remnants of a pouch and bracken lining, but neither of these sites indicated the presence of a solid lid for the pots. This leads to the question: why were these coin hoards abandoned? Several theories have been proposed. At Birnie, the pots were buried near roundhouses of the same period, with no evidence suggesting these burials were for sacred purposes. The most likely explanation for their abandonment is warfare, resulting in the death of those who knew the locations, though epidemics could have been equally responsible. Earlier theories linking the hoards’ locations to the proximity of the Antonine Wall are now considered unlikely. Macdonald initially suggested that the Wall’s re-entrant angle at the East Burn served as a visible landmark for the hoards’ placement, but this theory ignored other landscape features, such as the East Burn itself, which would have been a more suitable marker.If the Falkirk hoard was buried in an outer ditch of a hilltop enclosure, there would have been distinct man-made features nearby, possibly including a path between the enclosure and the water source. Similar to the Birnie site, the Falkirk hoard was likely placed near the owner’s residence. By the time the Falkirk hoard was buried, the Antonine Wall had been abandoned for over 80 years.

20世紀後半になると、フォークリックは急速に発展し、北部と南部に広がっていました。1920年代後半から1930年代にかけて、町の評議会はキャランダー・リッグスの東の地域の改善計画を推進しました。キャランダー・リッグスとその隣接地域は大規模な砂の採掘が行われており、ローズパークとベルモントの2つの大きな屋敷とその関連する土地は開発のために適していました。ベルモントとイースト・バーンの間には大きな土地があり、しばらくの間は単にメドウとして、後にベルズ・メドウとして知られていました。1920年代には、JGキャランダーによって設計された、印象的なバスステーションとキャランダー・リッグスに面する新しい店舗が建設され、フォークリックの最初の郊外ショッピングセンターが登場しました。この計画の一環として、フォークリック評議会はバスステーションとマーケット・スクエアの間を東に延ばす新しい道路を推し進め、これがメドウ・ストリートとなりました。その北側には労働交換所が開設されました。ダンとウィルソンはこの近くに製本所を設立し、キャランダー・リッグスの東端からメドウ・ストリートを北上してカース・レーンまでのアクセスを提供するため、クライスト・チャーチから土地を取得しました。ベルモントはフォークリック・メール新聞社(後に水道局)によってオフィスとして使用されていました。1933年8月、ジョン・ドークはバスステーションの隣に新しいダンスホールをオープンしました。この間も、バスの施設を拡大するためにベルズ・メドウで大量の砂が採掘され続けていました。1933年8月9日の水曜日、労働交換所の向かいのメドウ・ストリートを広げるために採石場の作業面を切り込んでいた数名の評議会作業員の一人、ロバート・ウォレスがスコップで何か固いものを打ちました。「最初は石を打ったと思った」とウォレス氏は後に語った、「でも、もう一度スコップで打つと、それは鉛のかけらのように思えた。戦争中にギリシャで宝物が掘り出されるのを経験していたので、スコップを投げ捨てて、手で砂を掻き分けた。すると、壺の一部が見えた。急いでそれを引き抜くと、私のジャケットの上に置いたとたんに割れてバラバラになり、たくさんの小さな丸い物体がぎっしりとくっついているのが現れた。それらの物体をよく見て、付着していた緑青をこすり取ると、それが銀貨だと分かった。仲間の何人かが主な塊から離れたコインに飛びついたが、私はそれらをジャケットで包み、道具小屋に持って行って鍵をかけた。」この発見のニュースはすぐに広まり、子供たちがあらゆる方角からさらなる発見を求めて参加しました。一部の人々はそれがいたずらだと思いました。町の書記官が呼ばれ、その午後に発見物を保管しました。

翌朝、町の書記官は発見された品物を検察官であるJGモリソン氏に渡し、彼は女王とロード・トレジャラーのリメンブランサーに通知しました。そして、そのコイン、壺、布は宝物として認定されました。8月12日にはフォークリック・ヘラルドに、採石場の砂の前で壺の底にコインが入った状態でウォレス氏が持っている写真が掲載されました。マムリルズのサム・スミス氏、家族の農場での考古学的発見で知られる尊敬されるローマ時代の愛好家が、発見現場を訪れてエディンバラの専門家にコメントを伝えました。発見地点は、後にオードナンス・サーベイの地図にメドウ・ストリートの南、現在のベルビュー・ストリートの近くとしてマークされました。しかし、スミス氏の意見は高く評価されており、実際の場所はもっと西、ワーミット・ヒルに近いと考えていました。この場所は、以前の地域の地形と合致し、後にバスステーションの一部となるドークのダンスホールがあったワーミット・ヒルの唯一の残りの部分に近いです。この位置情報は、1934年にマクドナルドが発表した内容に影響を与えた可能性があり、彼の発表によると、宝物は当時自然なくぼみまたはおそらくは溝の底に、現代の地表面から約7フィートの深さに埋められていたとされています。ウォレスの写真は昼頃に高い位置にある太陽の影から撮影されたことが示されており、彼が採石場の作業レベルでしゃがんでいるところ、つまり壺が発見された場所にいることがわかります。どうやら、宝物は元々存在した溝の底に埋められていたようで、その溝は約6フィートの深さで、上部が9フィートの幅があったと見られます。これは、ワーミット・ヒル周辺にあったとされる複数の溝の一つであり、地元の指導者の中心地であったと考えられています(ベイリー2017)。この考えは、1957年にベルズ・メドウの別の場所で、耕土層の下から発見された4世紀の銅合金製のコインによってさらに補強されています(ロバートソン1961、149)。その材質から、このコインは宝物の一部ではなく、先住民族による現地での継続的な居住を示しています。

これらのコインはエディンバラの国立古代博物館に送られ、スイスから休暇を終えて戻ったサー・ジョージ・マクドナルドによって調査されました。コレクションには合計1930枚のコインがあり、それぞれ約2.0gで、総重量は約3.860kgであることがわかりました。ウォレスは報酬を求め、地元の弁護士トーマス・キャセルズを雇い、宝物発見制度を利用しました。最初に提示された£25では不満で、彼はより高い報酬を求めて異議を唱えました。彼の法律顧問は、コインの本来の価値に基づいて、彼らのクライアントは地金の価値を受けるべきだと主張しました。この報酬に対する論争は地元の住民の間で物議を醸し出し、新聞に意見が寄せられました。一方、ウォレスの同僚たちが記念品として個々のコインを手に入れていたことも問題となりました。これは違法であると指摘され、10月3日にドル・パークのフォークリック博物館の名誉館長であるD.K.パターソンが、それらを博物館に返還するよう呼びかけました。彼は、そのようなコインはフォークリック博物館に保持され、訴追は行われないという合意をリメンブランサーとしていました。この呼びかけにより、ウォレス自身から3枚のコインと匿名の情報源から1枚が提出され、1963年にはさらに1枚が追加されました。

コインと一緒に発見された布は、初期の報告でほんの簡単に言及されていますが、フォークリック・タータンの年代を特定する上で重要です。最新のコインは230年にアレクサンダー・セウェルスのために鋳造されたもので、埋められる前に流通によって摩耗していたため、240年頃の日付が適切であると考えられます。コインの発見は、コインがローマ当局によって地元の指導者に対する「補助金」(つまり賄賂)として発行されたという文脈を提供しており、この見解は現在広く受け入れら

れています。コインと壺の取り扱いに重点が置かれていたにも関わらず、タータンが残っていることは幸運です。コインは壺を半分しか満たしていなかったことから、布はおそらくコインの上に置かれていたと思われ、もともとはかなり大きかったのでしょうが、宝物が地中に埋められた後、大部分が腐敗してしまった可能性があります。あるいは、ピットの砂の裏打ちからコインを隔てるために、小さな布片がコインの上に平らに置かれていた可能性もあります。モレイのバーニーで発見された同時代の別の宝物の2つの陶器容器のうちの1つには、コインの入った2つの革製の袋が含まれていたことから、時間をかけて複数回の支払いが行われた可能性があります。

バーニーの第二の容器にも革製の袋とシダの裏地の痕跡がありましたが、これらの遺跡のいずれにも壺のためのしっかりとした蓋の存在は示唆されていません。これにより、なぜこれらのコインの宝物が放棄されたのかという疑問が生じます。いくつかの説が提案されています。バーニーでは、壺は同時代の円形住居の近くに穴に埋められていましたが、これらの埋葬が聖なる目的のためであったという証拠はありません。放棄された最も可能性の高い説明は戦争であり、隠し場所を知っていた人々が死亡したことによるものですが、疫病による死も同様に考えられます。以前の声明にもかかわらず、アントニヌスの壁の近接性が重要であるとは考えられていません。マクドナルドは最初、イースト・バーンでの壁の後退角が隠された宝物の位置を測るための容易に認識できる視覚的な目印を提供したと提案しました。しかし、彼は壁の北側の風景が特徴のないものであると仮定していました。これは明らかに事実ではなく、近くのイースト・バーンでさえより良い目印を提供していたでしょう。壺が防御された丘の上の遺跡の外側の溝に掘り込まれていた場合、そこには人工的な特徴があり、遺跡と水源との間には道があった可能性があります。バーニーと同様に、フォークリックの宝物も所有者の居住地の近くに置かれていたと考えられます。フォークリックの宝物が埋葬された時には、アントニヌスの壁は既に80年以上も放棄されていました。