After securing the southern part of the island, the Roman forces shifted their focus to present-day Wales. The Silures, Ordovices, and Deceangli tribes steadfastly resisted the Roman conquest. For several decades, these tribes were the primary concern of the Roman military, despite sporadic minor rebellions from Roman-aligned tribes such as the Brigantes and the Iceni. The Silures were under the leadership of Caratacus, who conducted a successful guerrilla warfare against the Roman Governor Publius Ostorius Scapula. In the year 51, Ostorius managed to draw Caratacus into a direct battle and emerged victorious. The British chieftain sought sanctuary with the Brigantes, but their queen, Cartimandua, demonstrated her allegiance to Rome by handing him over to the Roman forces. Caratacus was taken to Rome as a prisoner, and his eloquent speech during Emperor Claudius’s triumph convinced Claudius to spare his life. However, the Silures continued to resist Roman rule, and following Caratacus, Venutius, Cartimandua’s former husband, became the leading figure in the British resistance.

When Nero became emperor, Roman control in Britain extended up to Lindum. Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, who had previously conquered Mauretania (now Algeria and Morocco), was appointed the governor of Britain. In 60 and 61, he led a campaign against the island of Mona (Anglesey), targeting the Druids in an attempt to eradicate their influence. Paulinus crossed the Menai Strait, executing a brutal massacre of the Druids and destroying their sacred sites.

島の南部を制圧した後、ローマ軍は現在のウェールズに焦点を移しました。シルリ族、オルドウィケス族、ディセングリ族は侵略者に対して断固として抵抗を続け、最初の数十年間はローマ軍の主要な関心事でした。これは、ブリガンテス族やイケニ族などのローマの同盟部族の間で時折起こる小規模な反乱にもかかわらずです。シルリ族はカラタクスに率いられ、彼はローマの総督プブリウス・オストリウス・スカプラに対して効果的なゲリラ戦を行いました。最終的に、51年にオストリウスはカラタクスを決戦に誘い込み、彼を打ち破りました。イギリスの首長はブリガンテス族の元へ逃れましたが、彼らの女王カルティマンドゥアは彼をローマ人に引き渡すことで忠誠を示しました。カラタクスは捕虜としてローマに連れて行かれ、クラウディウス帝の凱旋式での彼の威厳ある演説が皇帝に彼の命を救わせました。しかしながら、シルリ族は依然として平定されず、カラタクスの後を継いで、カルティマンドゥアの元夫ヴェヌティウスがイギリス抵抗運動の最も顕著なリーダーとなりました。

ネロが皇帝に即位した際、ローマのブリタニア(現在のイギリス)支配はリンダム(リンカン)まで広がっていました。マウレタニア(現在のアルジェリアとモロッコ)の征服者であるガイウス・スエトニウス・パウリヌスがブリタニアの総督に任命され、60年と61年にはドルイド教の根絶を目指してモナ島(アングルシー島)への遠征を行いました。パウリヌスはメナイ海峡を渡り、ドルイドたちを虐殺し、彼らの聖なる森を焼き払いました。

パウリヌスがモナで遠征中に、ブリタニアの南東部ではブーディカの指導の下で大規模な反乱が起こりました。彼女は最近亡くなったイケニ族の王プラスタガスの未亡人でした。ローマの歴史家タキトゥスによると、プラスタガスは遺言で自分の王国の半分をネロに残し、残りが手付かずで残されることを望んでいました。しかし、ローマは彼の願いを無視し、イケニ族の土地を全て強奪しました。ブーディカが抗議すると、ローマは彼女と彼女の娘たちを鞭打ちと強姦で罰しました。これに怒ったイケニ族とトリノヴァンテス族は、カムロドゥヌム(コルチェスター)のローマ植民地を破壊し、救援に向かった第九軍団の一部を撃破しました。パウリヌスは反乱の知らせを受け、反乱軍の次の標的であるロンディニウム(ロンドン)へ向かいましたが、そこが守れないと判断しました。その結果、ロンディニウムは放棄され、破壊され、続いてヴェルラミウム(セント・オールバンズ)も同様になりました。3つの都市で合計7万から8万人が死亡したと言われています。しかし、パウリヌスは残った二つの軍団を再編し、圧倒的な数の不利を覆し、ワトリング街道の戦いで反乱軍を打ち破りました。ブーディカはその後間もなく死亡しました。この時期、皇帝ネロはブリタニアからのローマ軍の完全撤退を検討さえしました。

Augustus planned invasions in 34, 27, and 25 BC, which never materialized, leading to a diplomatic and trade-focused relationship between Britain and Rome. Strabo, writing in Augustus’s time, noted that trade taxes were more lucrative than conquests. Archaeological evidence suggests increased import of luxury goods in southeastern Britain. Strabo also mentions British kings sending delegations to Augustus, who referenced receiving British kings as refugees.

In 16 AD, when some of Tiberius’s ships were blown off course to Britain, they returned with stories of monsters. Rome’s strategy in southern Britain seemed to support a power balance, favoring the Catuvellauni, led by Tasciovanus’s descendants, and the Atrebates, led by Commius’s descendants. This approach lasted until 39 or 40 AD, when Caligula planned a farcical invasion of Britain that never left Gaul. Claudius’s successful invasion in 43 AD supported another British ruler, Verica of the Atrebates.

アウグストゥスは紀元前34年、27年、25年に侵攻を計画しましたが、状況は決して好ましくありませんでした。その結果、ブリテンとローマの関係は外交と貿易に重点を置くものとなりました。アウグストゥスの治世の終わりに書かれたストラボの記述によると、貿易に課される税はどんな征服よりも多くの年間収益をもたらしたとされています。考古学的な証拠は、南東ブリテンで輸入された高級品が増加したことを示しています。ストラボはまた、アウグストゥスに使節を送ったブリテンの王たちについても言及しており、アウグストゥス自身の「レス・ゲスタエ」では、彼が避難民として受け入れた2人のブリテンの王について言及しています。紀元16年、ティベリウスの船がドイツでの遠征中に嵐でブリテンに流されたとき、彼らは怪物の話を持ち帰りました。

ローマは南ブリテンにおいて、力のバランスを保つことを奨励していたようです。特に、タスキオヴァヌスの子孫によって治められるカトゥウェラウニ族と、コミウスの子孫によって治められるアトレバテス族という2つの強力な王国を支援していました。この政策は、紀元39年または40年まで続きました。その時、カリグラはカトゥウェラウニ朝の亡命者を受け入れ、ブリテンへの侵攻を計画しましたが、ガリアを出発する前に茶番と化しました。クラウディウスが紀元43年に成功した侵攻を行ったとき、それはアトレバテスの別の亡命者であるヴェリカを支援するためでした。

In 43 AD, Aulus Plautius led the initial Roman invasion into Britain, though the exact number of legions involved remains uncertain. The Legio II Augusta, under the command of the future emperor Vespasian, is confirmed to have participated. Other legions likely present from the outset, including the Legio IX Hispana, XIV Gemina (later known as Martia Victrix), and the XX (later Valeria Victrix), were actively involved in the Boudican Revolt of 60/61. The Roman army’s flexibility meant units were frequently relocated as needed. Notably, the IX Hispana was stationed in Eboracum (York) by 71 and mentioned in an inscription dated 108, before its eventual demise in the eastern provinces, possibly during the Bar Kokhba revolt.

The invasion faced initial setbacks due to a mutiny among the troops, resolved only after an imperial freedman convinced them to brave the crossing of the Ocean and campaign in uncharted territories. The forces divided into three groups, likely making landfall at Richborough, Kent, and possibly near Fishbourne, West Sussex.

The Romans faced the Catuvellauni and their allies in two major battles. Assuming a Richborough landing, the first battle occurred near the river Medway, and the second by the river Thames. Togodumnus, one of the British leaders, was killed, but his brother Caratacus continued the resistance. Plautius waited at the Thames for Emperor Claudius, who brought reinforcements, including elephants and artillery, for the march to the Catuvellaunian capital, Camulodunum (Colchester). Vespasian pacified the southwest, Cogidubnus was installed as a client king, and Rome negotiated treaties with tribes outside their direct control.

紀元43年、アウルス・プラウティウスがローマの初のブリテン侵攻を率いたが、参加した軍団の正確な数は不明である。将来の皇帝ヴェスパシアヌスが指揮する第二アウグスタ軍団が参加したことが確認されている。第九ヒスパナ軍団、第十四ゲミナ軍団(後にマルティア・ウィクトリクスとして知られる)、第二十軍団(後にウァレリア・ウィクトリクス)も、60/61年のブーディカの反乱中に活動しており、おそらく初期の侵攻から存在していたと考えられる。ローマ軍の柔軟性により、必要に応じて部隊が頻繁に移動していた。特に、第九ヒスパナ軍団は71年にエボラクム(ヨーク)に駐留しており、108年の建設碑文に記されているが、最終的に帝国の東部で、恐らくバル・コクバの反乱中に壊滅した。侵攻は、兵士たちの反乱により初期に遅れをとったが、皇帝の解放奴隷が彼らを説得して未知の世界を超えた遠征への恐れを克服させた。軍は三つのグループに分かれ、ケントのリッチボローに上陸したと考えられ、一部の部隊はウェスト・サセックスのフィッシュボーン近くに上陸した可能性がある。

ローマ軍は、カトゥウェラウニ族とその同盟者たちと二度の大規模な戦闘を行った。リッチボロー上陸を仮定すると、最初の戦闘はメドウェイ川近くで、二度目の戦闘はテムズ川で行われた。ブリトンの指導者の一人、トゴドゥムヌスは戦死したが、その兄弟カラタクスは他の場所で抵抗を続けた。プラウティウスはテムズ川で待機し、クラウディウス帝が象や大砲を含む増援部隊と共に到着し、カトゥウェラウニ族の首都カムロドゥヌム(コルチェスター)への最終進軍を行った。ヴェスパシアヌスは南西部を平定し、コギドゥブヌスを友好的な王として複数の領土に据え、ローマは直接支配していない部族と条約を結んだ。

In 69 AD, a period known as the “Year of the Four Emperors,” brought significant upheaval. Amidst the civil war in Rome, the governors in Britain, weakened by the chaos, struggled to maintain control over the legions. This situation provided an opportunity for Venutius of the Brigantes tribe. Previously, the Romans had defended Cartimandua against Venutius, but this time, they were unable to assist her. Cartimandua was safely evacuated, leaving Venutius in control of northern Britain. After Emperor Vespasian stabilized the Roman Empire, he appointed Quintus Petillius Cerialis and Sextus Julius Frontinus as governors, who were tasked with subjugating the Brigantes and Silures, respectively. Frontinus extended Roman dominance over all of South Wales and began exploiting its mineral wealth, including the gold mines at Dolaucothi.

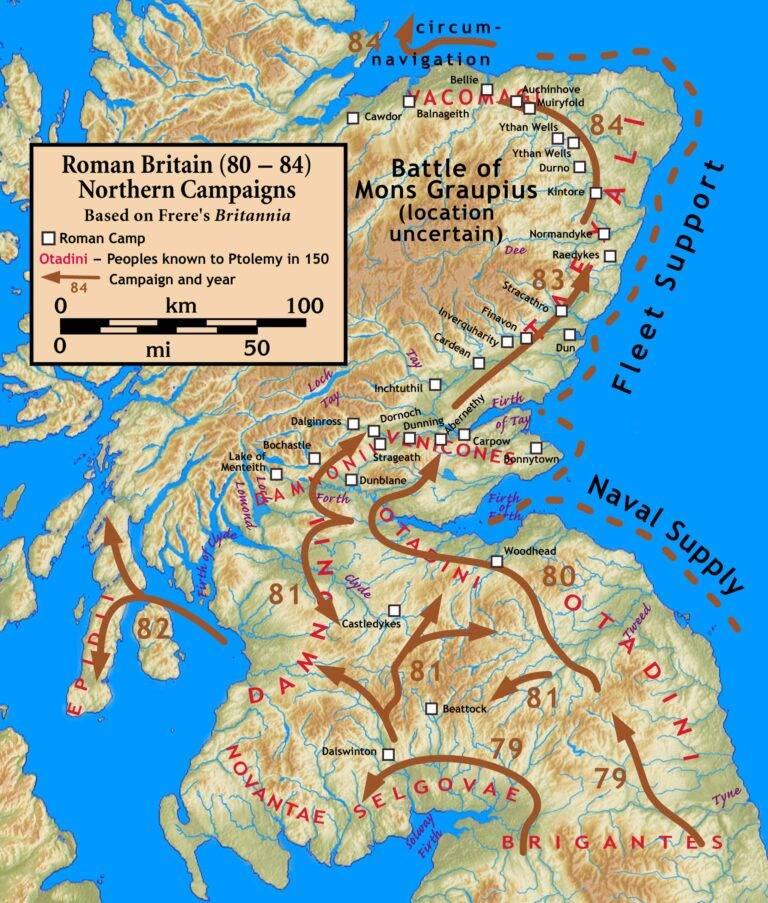

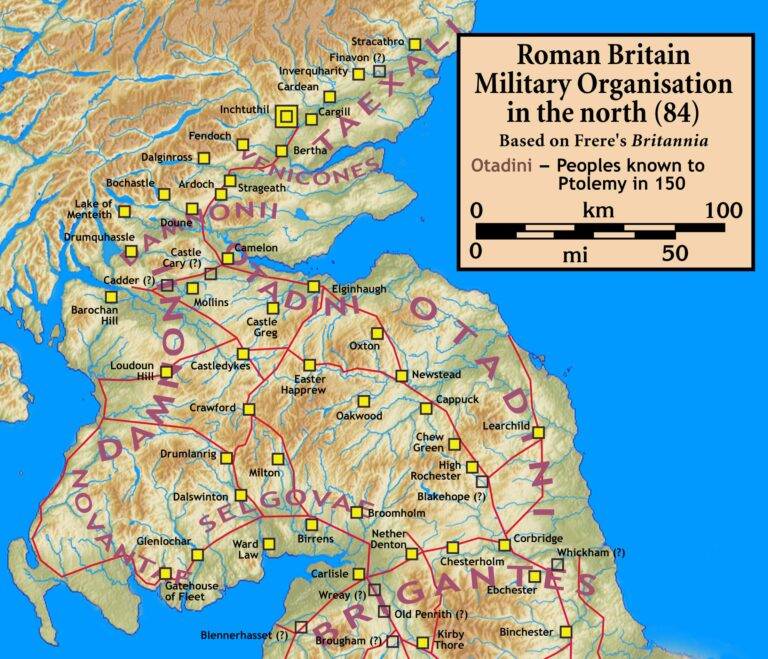

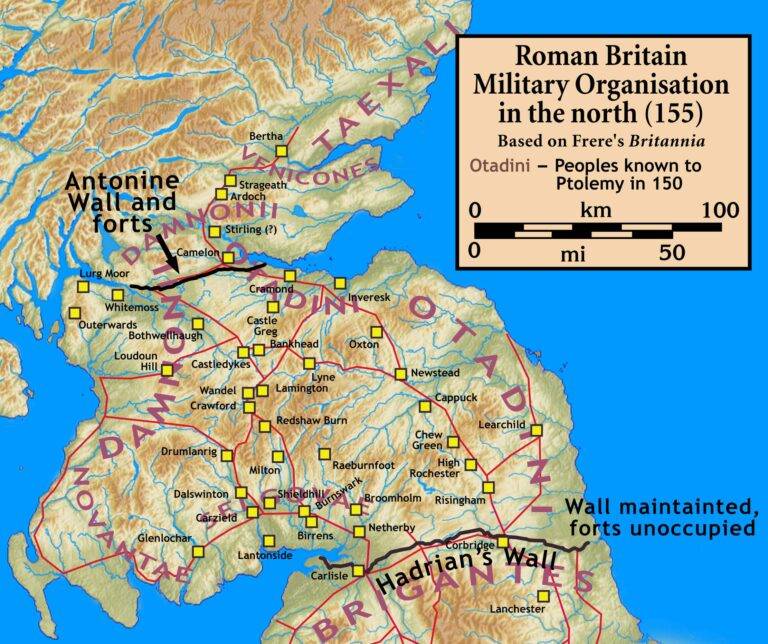

In the subsequent years, Roman conquests in Britain continued, expanding the area under Roman control. In 78 AD, Governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who was the father-in-law of the historian Tacitus, subdued the Ordovices. With the XX Valeria Victrix legion, he defeated the Caledonians in 84 AD at the Battle of Mons Graupius in north-east Scotland. This battle marked the zenith of Roman territorial expansion in Britain. However, shortly after this victory, Agricola was recalled to Rome, and the Romans retreated to a more defensible position along the Forth-Clyde isthmus, thereby freeing up troops for other frontiers.

Throughout the Roman occupation of Britain, a substantial military presence was necessary. Consequently, the emperors often appointed trusted senior officials as governors of the province. This led to several future emperors, including Vespasian, Pertinax, and Gordian I, serving in governing or military capacities in Roman Britain.

西暦69年、”四皇帝の年”として知られる時期に、さらなる混乱が起こりました。ローマで内戦が激化する中、ブリタニアの弱体化した総督たちは軍団を制御することができず、ブリガンテス族のヴェヌティウスはこのチャンスをつかみました。以前、ローマ人は彼に対抗してカルティマンドゥアを守っていましたが、今回はそうすることができませんでした。カルティマンドゥアは避難させられ、ヴェヌティウスが北部の国を支配することになりました。皇帝ウェスパシアヌスが帝国を安定させた後、彼の最初の二人の総督、クインティウス・ペティリウス・ケリアリスとセクストゥス・ユリウス・フロンティヌスは、それぞれブリガンテス族とシルリ族の鎮圧に取り組みました。フロンティヌスは南ウェールズ全域をローマ支配下に置き、ドラウコシの金鉱山などの鉱物資源の開発を開始しました。

その後の数年間で、ローマはブリタニア島のさらなる地域を征服し、ローマ支配の範囲を拡大しました。総督グナエウス・ユリウス・アグリコラ、歴史家タキトゥスの義父は、78年にオルドウィケス族を征服しました。XXウァレリア・ウィクトリクス軍団とともに、彼は84年にスコットランド北東部のモンス・グラウピウスの戦いでカレドニア人を打ち破りました。この戦いは、ブリタニアにおけるローマの領土拡大の最高潮を示すものでした。しかし、この勝利の直後、アグリコラはローマに呼び戻され、ローマ人は初めフォース・クライド地峡に沿ったより防御しやすい線まで後退し、他の境界線に緊急に必要な兵士を解放しました。

その後の数年間で、ローマはブリタニア島のさらなる地域を征服し、ローマ支配の範囲を拡大しました。総督グナエウス・ユリウス・アグリコラ、歴史家タキトゥスの義父は、78年にオルドウィケス族を征服しました。XXウァレリア・ウィクトリクス軍団とともに、彼は84年にスコットランド北東部のモンス・グラウピウスの戦いでカレドニア人を打ち破りました。この戦いは、ブリタニアにおけるローマの領土拡大の最高潮を示すものでした。しかし、この勝利の直後、アグリコラはローマに呼び戻され、ローマ人は初めフォース・クライド地峡に沿ったより防御しやすい線まで後退し、他の境界線に緊急に必要な兵士を解放しました。

ローマのブリタニア統治の歴史の大部分において、大量の兵士が島に駐留していました。これにより、皇帝は信頼できる高官を省の総督として配置する必要がありました。その結果、多くの将来の皇帝たち、ウェスパシアヌス、ペルティナクス、ゴルディアヌス1世を含む、がこの省で総督または軍団司令官として務めました。

The Caledonians, known in Latin as Caledones or Caledonii and in Greek as Καληδῶνες (Kalēdōnes), were a confederacy of Celtic, Brittonic-speaking tribes located in present-day Scotland during the Iron Age and Roman periods. The Greek version of their tribal name led to their territory being called Caledonia. Initially considered part of the Britons, the Caledonians were later distinguished from the southern Britons as Picts, especially after the Roman conquest of southern Britain. These northern inhabitants, presumably related to the Britons and speaking a similar language, were recognized as distinct. Consequently, the Caledonian Britons were adversaries of the Roman Empire, which governed most of Great Britain as the Roman province of Britannia.

According to the analysis of German linguist Stefan Zimmer, the name ‘Caledonia’ originates from the tribal name ‘Caledones’ (which is a Latinized form of the Brittonic nominative plural n-stem ‘Calīdones’). Zimmer proposes that this name means “possessing hard feet,” a phrase that suggests steadfastness or endurance. This interpretation comes from the Proto-Celtic roots “*kal-” meaning “hard” and “*φēdo-” meaning “foot.” Furthermore, the singular form of this ethnic name appears as ‘Caledo’ (a Latinization of the Brittonic nominative singular n-stem ‘*Calidū’), as found on a Romano-British inscription in Colchester.

The Caledonians, like other Celtic tribes in Britain, were known for building hillforts and for their agricultural practices. They had both victories and defeats against the Romans and never came under full Roman occupation despite numerous attempts. The majority of information about the Caledonians comes from Roman sources, which might be biased.

Historian Peter Salway suggests that the Caledonians were likely Pictish tribes speaking a language akin to Common Brittonic, perhaps a variant of it, and possibly bolstered by Brythonic resistance fighters who fled from Roman-occupied Britannia. The Caledonian tribe, giving its name to the historical Caledonian Confederacy, might have been allied in their struggle against Rome with other tribes in north-central Scotland, such as the Vacomagi, Taexali, and Venicones as noted by Ptolemy. The Romans managed to establish agreements with certain Brythonic tribes like the Votadini, using them as effective buffer states.

In his work “Agricola,” written around 98 AD, Tacitus described the Caledonians as having red hair and large limbs, traits he attributed to Germanic origins, stating, “The reddish hair and large limbs of the Caledonians proclaim a German origin.” Similarly, Jordanes, in his “Getica,” observed that the inhabitants of Caledonia had reddish hair and large, loosely jointed bodies.

Eumenius, who praised Constantine Chlorus, also noted that both the Picts and Caledonians had red hair. This observation aligns with William Forbes Skene’s recognition of Tacitus’ portrayal of the Caledonians with red hair in “Agricola.”

James E. Fraser proposed a different perspective, suggesting that Tacitus and other Romans might have been aware of the Caledonians dyeing their hair red, a practice potentially misinterpreted as a racial characteristic. Fraser also pointed out that the pressures faced by northern tribes, leading to their migration, could have resulted in the development of unique tribal identifiers, such as specific styles of clothing or jewelry. Early examples of such identifiers include armlets, earrings, button covers, and ornately decorated weapons.

カレドニア人(発音:/ˌkælɪˈdoʊniənz/;ラテン語:Caledones または Caledonii;ギリシャ語:Καληδῶνες, Kalēdōnes)またはカレドニア連合は、鉄器時代およびローマ時代の現在のスコットランドにあったブリトン諸語(ケルト語派)を話す部族連合でした。部族名のギリシャ語形が彼らの領土の名前であるカレドニアとなりました。カレドニア人は当初、ブリトン人の一派とみなされていましたが、南部ブリタニアのローマ征服後、北部の住民はピクト人として区別され、これらもブリトン語を話す関連する民族と考えられました。したがって、カレドニアのブリトン人は、大部分のブリタニアを支配していたローマ帝国の敵でした。

ドイツの言語学者ステファン・ツィマーによると、「カレドニア」という名前は、部族名「カレドネス」(ブリトン語の主格複数形n-語幹「Calīdones」のラテン語化)から派生しており、彼はこれを「堅い足を持つ」という意味で語源分析しています(「忍耐力や不動の意志を表す」という意味から、プロト・ケルト語の根「*kal-」(堅い)と「*φēdo-」(足)に由来します)。この民族名の単数形は「カレド」(ブリトン語の主格単数形n-語幹「*Calidū」のラテン語化)として、コルチェスターのローマ・ブリトン時代の碑文に記録されています。

カレドニア人は、ブリタニアの他の多くのケルト部族と同様に、丘の要塞の建設者であり農業を行っていた人々で、ローマ人に何度か勝利し、また敗北を喫しました。ローマ人はカレドニアを完全に占領することは決してありませんでしたが、複数回の試みが行われました。カレドニア人に関するほとんどすべての情報は、偏見を持つ可能性のあるローマの資料に基づいています。

歴史家のピーター・サルウェイは、カレドニア人はおそらくピクト語を話す部族であり、ブリトン語やその一派に非常に近い言語を話していたと考えています。また、ローマ支配下のブリタニアから逃れたブリトン語抵抗戦士によって強化された可能性があります。歴史上のカレドニア連合の名前の由来となったカレドニア部族は、プトレマイオスによって記録されている北中央スコットランドの部族、例えばヴァコマギ族、タエクサリ族、ヴェニコネス族とともにローマとの戦いに参加していた可能性があります。ローマ人はヴォタディニ族などのブリトン部族と協定を結び、効果的な緩衝州として利用しました。

紀元98年頃に書かれた『アグリコラ』において、タキトゥスはカレドニア人を赤い髪と大きな体格を持つと描写し、これをゲルマン起源の特徴と考えていました。「カレドニア人の赤い(rutilae)髪と大きな四肢は、彼らがゲルマン起源であることを示している」と述べています。同様に、ヨルダネスは彼の『ゲティカ』で、「カレドニアの住民は赤い髪と大きく緩やかに組み合わされた体を持っている」と書いています。

コンスタンティヌス・クロルスの賛美者であるエウメニウスも、ピクト人とカレドニア人の両方が赤い髪(rutilantia)を持っていたと記述しています。ウィリアム・フォーブス・スキーンなどの学者は、この記述がタキトゥスの『アグリコラ』におけるカレドニア人の赤い髪の描写と一致することに注目しています。

ジェームズ・E・フレイザーは、タキトゥスや他のローマ人がカレドニア人が髪を赤く染める方法を知っていた可能性があり、これが民族的特徴として誤解された可能性があると主張しています。フレイザーはまた、北部の部族にかかった圧力が彼らを移動させることになり、特定の部族固有の識別子、例えば衣服や宝飾品の創造につながった可能性があるとも述べています。そのような識別子の最も初期の例には、腕輪、イヤリング、ボタンカバー、装飾された武器などが含まれています。