THE PICTS

Dunnicaer(またはDun-na-caer)は、スコットランドのアバディーンシャー沿岸、ダンノッター城とストーンヘブンの間に位置する険しい海の岩山です。アクセスが難しいにもかかわらず、1832年にはその頂上でピクト族の象徴石が発見され、21世紀の考古学では、その石を構造の一部に取り入れた可能性のあるピクト族の丘の砦の証拠が発見されています。これらの石は3世紀または4世紀に刻まれた可能性がありますが、これは最も単純で最も古い(クラスI)象徴石が5世紀または7世紀にさかのぼるという一般的な考古学的見解に反します。

ストーンヘブンと同様に位置するダンノッター城の間に位置するこの海の岩山は、ストラスレイサン湾にあり、北にダウニー・ポイント、南にボウダン・ヘッドの崖から沖合に位置しています。満潮時には本土から切り離され、平らで草の生えた頂上は、約30~35メートル(100~115フィート)の険しい崖に完全に囲まれています。この岩石は古い赤砂岩です。丘の砦があった当時、この場所は岬だったかもしれず、その後の崖の浸食により、現在のような20×12メートル(66フィート×39フィート)の平らな頂上を持つ岩山に変わったのですが、ピクト時代にはもっと大きかったでしょう。

1977年と1982年に行われた頂上での考古学的調査では、特に重要な発見はありませんでした。2015年にはアバディーン大学のチームによる新たな発掘が始まり、丘の砦の存在が明らかになり、その後の年にも発掘が続けられました。そこには、本土に向かって南西に延びる木材で囲まれた石の城壁がありました。木材の放射性炭素年代測定から、この砦は紀元2世紀から4世紀の間に使用されていたとされ、スコットランドで最も古いピクト族の砦とされています。暖炉や内部の部屋の基礎が発見されました。ガラス、サミアン焼き器、ブラック・バーニッシュド焼き器の陶器、鉛の重りなどが発掘されました。これはローマ帝国の国境よりも北にある場所でこれらの品を見つけるのは珍しいことです。何世紀にもわたって、周囲の崖の浸食により砦の一部は特に東側に崩れ落ちています。これらの発見から、この砦は遠方から持ち込まれた石とオークの木材を使った、重要な地位を持つ建物だったことが示唆されています。その後、この場所は放棄された可能性があります。住人がダンノッターに移動したため、または岩山の浸食による問題のためかもしれません。

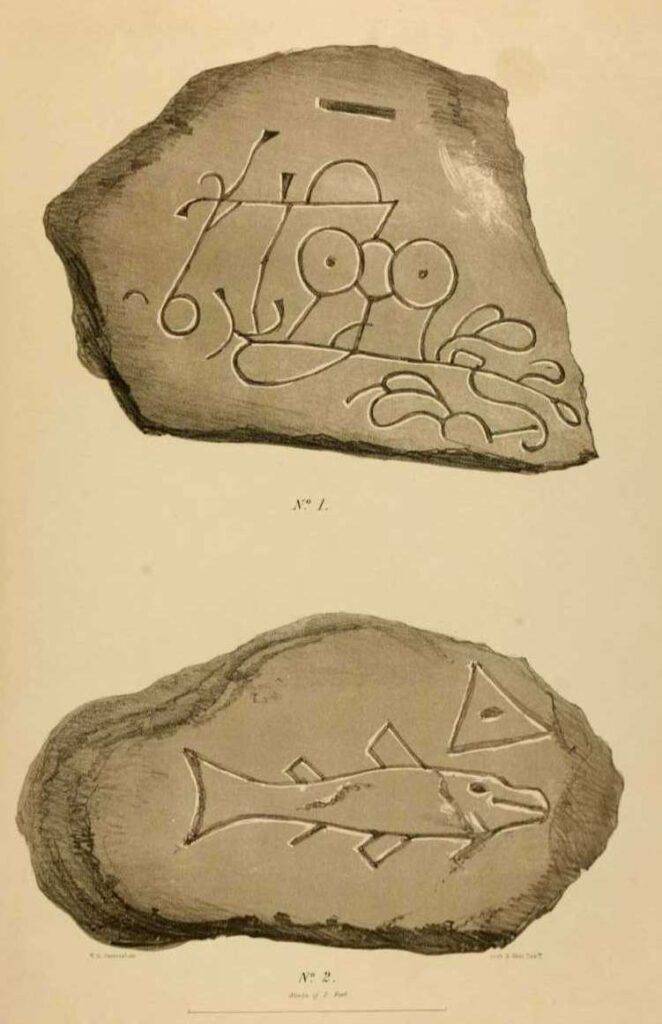

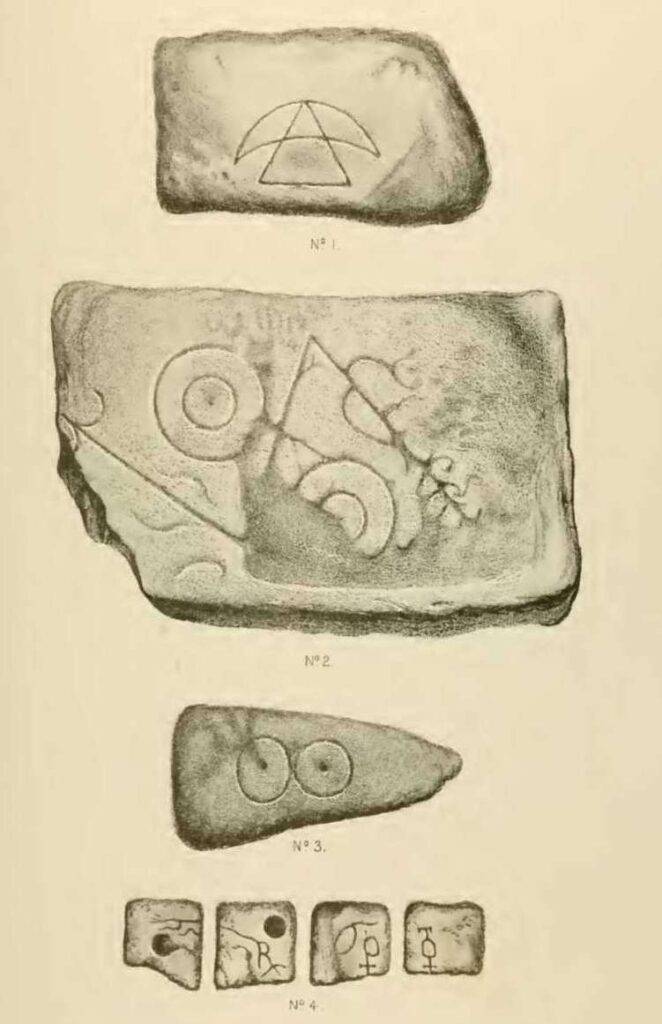

早くも1819年には、暖炉の石として使用するために岩山から象徴石が取り外されましたが、その刻印にはほとんど関心が寄せられませんでした。1832年には、若者たちが登って頂上の高原に壁を発見しました。彼らはいくつかの石を海に投げ落とし、後に回収された時、その中にはピクト族の象徴石が含まれていました。1857年には、これらの象徴石がアレクサンダー・トムソンによって文書化されました。ジョン・スチュアートによる1856年と1867年の「スコットランドの彫刻された石」の巻にこれらが描かれています。1992年にはこれらの象徴の徹底的な説明が出版されました。1つの石は現在マリシャル博物館にあり、他の石はバンコリー・ハウスにあります。石のデザインと比較的小さいサイズは珍しく、それらは早期のものであることを示しています。それらは紀元3世紀から4世紀にさかのぼる城壁の壁に埋め込まれていた可能性があります。これは、最も単純で最も早い(クラスI)の石が5世紀または7世紀にさかのぼるという従来の見解よりもずっと早い日付です。

ストーンヘブンと同様に位置するダンノッター城の間に位置するこの海の岩山は、ストラスレイサン湾にあり、北にダウニー・ポイント、南にボウダン・ヘッドの崖から沖合に位置しています。満潮時には本土から切り離され、平らで草の生えた頂上は、約30~35メートル(100~115フィート)の険しい崖に完全に囲まれています。この岩石は古い赤砂岩です。丘の砦があった当時、この場所は岬だったかもしれず、その後の崖の浸食により、現在のような20×12メートル(66フィート×39フィート)の平らな頂上を持つ岩山に変わったのですが、ピクト時代にはもっと大きかったでしょう。

1977年と1982年に行われた頂上での考古学的調査では、特に重要な発見はありませんでした。2015年にはアバディーン大学のチームによる新たな発掘が始まり、丘の砦の存在が明らかになり、その後の年にも発掘が続けられました。そこには、本土に向かって南西に延びる木材で囲まれた石の城壁がありました。木材の放射性炭素年代測定から、この砦は紀元2世紀から4世紀の間に使用されていたとされ、スコットランドで最も古いピクト族の砦とされています。暖炉や内部の部屋の基礎が発見されました。ガラス、サミアン焼き器、ブラック・バーニッシュド焼き器の陶器、鉛の重りなどが発掘されました。これはローマ帝国の国境よりも北にある場所でこれらの品を見つけるのは珍しいことです。何世紀にもわたって、周囲の崖の浸食により砦の一部は特に東側に崩れ落ちています。これらの発見から、この砦は遠方から持ち込まれた石とオークの木材を使った、重要な地位を持つ建物だったことが示唆されています。その後、この場所は放棄された可能性があります。住人がダンノッターに移動したため、または岩山の浸食による問題のためかもしれません。

早くも1819年には、暖炉の石として使用するために岩山から象徴石が取り外されましたが、その刻印にはほとんど関心が寄せられませんでした。1832年には、若者たちが登って頂上の高原に壁を発見しました。彼らはいくつかの石を海に投げ落とし、後に回収された時、その中にはピクト族の象徴石が含まれていました。1857年には、これらの象徴石がアレクサンダー・トムソンによって文書化されました。ジョン・スチュアートによる1856年と1867年の「スコットランドの彫刻された石」の巻にこれらが描かれています。1992年にはこれらの象徴の徹底的な説明が出版されました。1つの石は現在マリシャル博物館にあり、他の石はバンコリー・ハウスにあります。石のデザインと比較的小さいサイズは珍しく、それらは早期のものであることを示しています。それらは紀元3世紀から4世紀にさかのぼる城壁の壁に埋め込まれていた可能性があります。これは、最も単純で最も早い(クラスI)の石が5世紀または7世紀にさかのぼるという従来の見解よりもずっと早い日付です。

- Origins and Location: The Picts are first mentioned in Roman sources in the late 3rd century CE. They inhabited the area of modern-day Scotland north of the Forth and Clyde rivers.The Pictish Kingdom, known for its enigmatic and unique culture, was a political entity during the Late Iron Age and Early Medieval periods in what is now eastern and northern Scotland. Here are some key aspects of the Pictish Kingdom:

The Yellow Plague between 549-552 seems to have caused a major division in Pictland, resulting in the formation of two distinct kingdoms separated by a north-south divide. Before this event, the rulers of what later became known as North Pictland were dominant and regained their dominance after this divided period. The plague impacted the Britons of the island more severely than the Saxon invaders, ultimately tipping the power balance in favor of the Saxons. This turmoil may have also enabled the Bernician Angles to establish their own kingdom on the north-eastern coast of Britain, soon becoming a formidable foe of the Picts. The Picts lost at least one king, Drust mac Munaith, in 552, which likely contributed to this division.

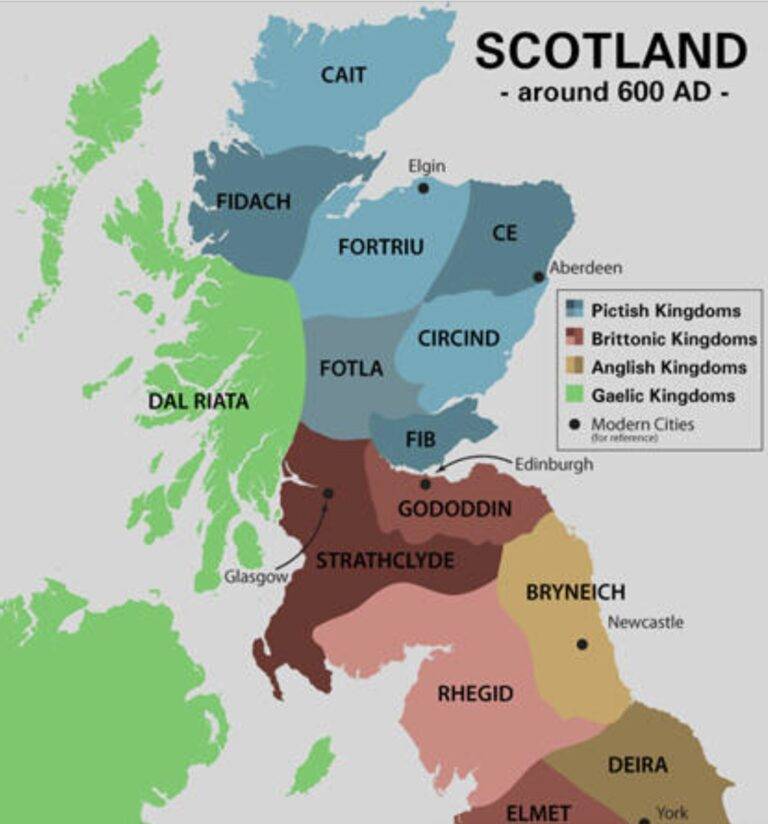

The capital of Fortriu, one of the stronger southern sub-kingdoms known as Verturiones to the Romans and now Forteviot, was Scone. To its east was the sub-kingdom of Fib, now remembered as Fife, sometimes still called the Kingdom of Fife. Other sub-kingdoms included Fotla, Fidach, Circind, and Ce, all named after the sons of a legendary Pictish king, Cruithne, in Gaelic folklore. Cruithne, said to have ruled for a century, had seven sons, each named after one of Pictland’s seven provinces, as mentioned in the ancient Scottish text, De Situ Albanie.

South Pictland’s independence from the north might have been brief, explaining the scant details about its kings. Yet, the Pictish center at Burghead, which flourished in the eighth century when the Picts united into a single kingdom, was part of Fortriu.

St Ninian converted the southern Picts to Christianity in the late 4th or early 5th century, predating St Patrick’s work in Ireland. This is evidenced by St Patrick referring to the South Picts as apostates, indicating a renouncement of Christianity, likely between AD 400-450, possibly after a king’s death. A similar return to paganism after a leader’s death occurred among the East Saxons and Northumbrians. Tradition suggests Ninian died in 432 in Ireland, which would be too early for him to have converted the Picts personally, suggesting his followers likely continued his mission.

(Sources include Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson; “A History of the English Church and People” by The Venerable Bede, translated by Leo Sherley-Price and revised by R E Latham; “Early Sources of Scottish History AD 500-1286, Volume 1” by Alan Orr Anderson; “Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain AD 550-850” by Leslie Alcock; “Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80-1000” by Alfred P Smyth; “Incredible” archaeological findings at a Pictish power center reported by Alison Campsie in The Scotsman; and “De Situ Albanie”, discussed in the Caithness Field Club Bulletin, Oct 1978.)

ピクト王国は、後期鉄器時代から初期中世にかけて、現在のスコットランドの東部と北部に存在した独特の文化を持つ政治的実体でした。ピクト王国についての主な特徴は以下の通りです:

起源と位置:ピクト人は3世紀後半のローマの資料で初めて言及されています。彼らは現在のスコットランドのフォース川とクライド川の北部に居住していました。

言語と文字:ピクト語はよく分かっていないが、ウェールズ語、コーンウォール語、ブルトン語に関連するブリソン語族の言語であったと考えられています。ピクト人は独自の記号システムを使用しており、これは主に立石に彫られています。これらの記号の意味は学術的な議論の対象となっており、宗教的なシンボルから書かれた言語の形態までさまざまな解釈があります。

社会と文化:ピクト社会は部族的であり、他のケルト人と同様に戦士のエリート層を持っていました。初期の資料ではしばしば猛烈な戦士として描かれています。特に象徴的な石碑や金属工芸品に見られる彼らの文化は、高度な技術力で知られています。

宗教:初期にはケルトの多神教を実践していましたが、6世紀にセント・コルンバによってキリスト教に改宗しました。

ピクト美術:石碑、ジュエリー、金属工芸品に見られるピクト美術は、その複雑なデザインで有名です。特に独自の記号や彫刻が施された象徴的な石碑が注目されています。

他の王国との交流:ピクト人はローマ人としばしば敵対的な交流を持ち、ローマ人はピクト人や他の部族をブリタニアから遮断するためにアントニヌスの長城やハドリアヌスの長城を建設しました。また、隣接するゲール人、ブリトン人、ヴァイキングとも交流がありました。

衰退と遺産:ピクト王国は徐々にゲールのダルリアダ王国と合併し、アルバ王国を形成し、最終的にはスコットランドになりました。11世紀までに、ピクトのアイデンティティはこの新しい王国に吸収されましたが、彼らの影響はスコットランドの文化と歴史に残っています。

ピクト人はほとんど書面記録を残していないため、その歴史は謎に包まれています。彼らについて知られていることの多くは、考古学的な証拠や隣接する文化、特にローマ人やゲール人からの記録に基づいています。

549年から552年の黄色疫病がピクトランドを北部と南部の2つの明確に定義された王国に分裂させたようです。この前までは、後に北ピクトランドとなる地域の王が支配的であり、この分裂の時期が終わると再び支配的になります。疫病は島のブリトン人にサクソン侵略者よりも遥かに深刻な影響を与え、後者に有利に力のバランスを移行させました。この混乱はおそらくベルニシアのアングル人がブリテン島の北東海岸に自身の王国を築くことを可能にしました。これはすぐにピクト族の強敵となります。ピクト族自身も少なくとも一人の王、552年のドゥルスト・マク・ムナイスを失い、これが分裂を可能にしたと思われます。

スコーンは南部の最も強力な従属王国の首都で、フォートリウ(ローマ人にはヴェルトゥリオネス、現代ではフォーテヴィオット)でした。東部の従属王国フィブは現在のファイフとして知られ、時折ファイフ王国として言及されます。残りの四つはフォトラ、フィダック、サーキンド、そしてケで、これらの名前は古代のピクト王クルイトネの息子たちに帰せられています(「アン・クルイタイン」、ゲール語で「ピクト」を意味し、「塗られた人々」を自然に意味します)。クルイトネは100年間統治し、7人の息子を持っていた(7という数字はピクト族にとって非常に重要であった)が、彼らはそれぞれピクトランドの7つの州にちなんで名付けられました。これは「デ・シツ・アルバニエ」という古代のスコットランドの記述に詳述されています。

南ピクトランドは短期間のみ北部から独立していた可能性があり、これはこの地域の王たちの詳細が少ないことを説明するかもしれません。しかし、重要なピクト中心地バーグヘッドは8世紀、ピクトが単一の王国に統一された後にピークに達し、バーグヘッドはフォートリウの領域内にしっかりと位置しています。

南ピクト族は4世紀後半から5世紀初頭に聖ニニアンによってキリスト教に改宗されました。彼は「使徒」として知られるようになりました。彼の活動はアイルランドの聖パトリックよりも先で、後者は南ピクト族が背教者であると述べています。これは彼らがキリスト教への改宗を放棄したことを意味し、おそらくAD 400-450年の間、おそらくは王の死後に起こったでしょう。東サクソン族やノーサンブリア人の間でも、指導者の死後に異教への逆戻りが見られます。伝統によれば、ニニアンは432年にアイルランドで亡くなりましたが、これは彼がピクト族を改宗させるには早すぎるようです。より可能性が高いのは、彼の名前で彼の信者たちによって主に行われた作業です。

(ピーター・ケスラーによる情報、エドワード・ドーソンによる追加情報、ヴェネラブル・ベーデによる「イングランド教会と民衆の歴史」(レオ・シャーリー=プライス翻訳 – R E L Lathamによる改訂)、アラン・オア・アンダーソンによる「スコットランド史初期資料 AD 500-1286 第1巻」(ポール・ワトキンス、スタンフォード1990年再印刷)、レスリー・アルコックによる「北ブリテン AD 550-850 の王と戦士、職人と司祭」(スコットランド古物研究会、エディンバラ、2003年)、アルフレッド・P・スマイスによる「戦士と聖人:スコットランド AD 80-1000」(1984年)、そして外部リンク:「ピクトのエリート権力中心地で考古学者が見つけた信じられない発見」、アリソン・キャンプシー(スコッツマン)、そして「デ・シツ・アルバニエ」(F T Wainwrightによると14世紀に書かれた可能性があり、1978年10月のカイスネス・フィールド・クラブ・ブレティンで議論されています)。)

552年 – 580年 ガラム・ケンネラス / ティゲルナク年代記に記載。

556年 – 565年 ガラム・ケンネラスの治世中、南部は北ピクトランドの強力なブルデイ・マク・マエルコンによってある程度征服されます。しかし、南ピクト王国は独立した実体というよりは、北部に緩く統治された地域である可能性があります。この問題に対する決定的な答えは、利用可能な証拠が不足しているため出せません。

578年/580年 – ? ガラム・ケンネラスの死は578年か580年とされます。南部の王の名前がないことから、それがより直接的に北ピクトランドによって統治されている可能性があります。この時点でブルデイ・マク・マエルコンが王座にいて、4年後にその娘婿が後を継ぎます。

603年 ダル・リアダのアエダン・マク・ガブランがアングル人の王国ベルニシアを侵攻し、デグサスタンの戦いで王エセルフリスに攻撃します。ダル・リアダを打ち破ることで、エセルフリスはその敵である南ピクト族と同盟を結びます。この同盟は、エセルフリスのライバルであるエドウィンが王座に就くまで続きます。

668年 南部の地域はオスウィウによるノーサンブリアのアングル人によって征服されます。明らかにノーサンブリアはピクト族と敵対しており、南部の可能な王であるタローンは彼らに殺されますが、この敵対関係が後の世代でピクト族とダル・リアダのスコット人とのより密接な関係を強制するかもしれません。 681年 ノーサンブリアはアバーコーンで南ピクト族の間にトルムウィン司教の司教座を設立します。ピクト族を改宗させる努力はわずか4年後に失敗し、ダンニケンの戦いで北ピクト族がノーサンブリアを打ち負かした直後に放棄されます。

668年 北ピクト族は長い間南ピクト族を支配しており、この時点までに – もしその前でなければ – ブルデ・デレレイの指揮の下で統一されたピクトランドが形成されています。彼は今や北ピクト族の最後の弱い王、タラン・マク・エンティフィディクを廃位します。

1 Cait (or Cat):

Location: Corresponds to modern Caithness and Sutherland.

Characteristics: Cait was situated at the northern tip of Scotland, known for its coastline and vast highlands. The region likely had strong community ties, with fishing and agriculture being significant activities.

2 Ce:

Location:

Located in what is now Mar and

Buchan.

Characteristics: Ce was in the eastern part of Scotland, an area rich in farmland, where agriculture and livestock were probably key economic activities. It may also have been a central point for trade routes.

3 Circin:

Location: Possibly in modern Angus and the Mearns.

Characteristics: Circin was known for its fertile lands and quality farmland, likely focusing on grain production. Its proximity to the coast also suggests that fishing and trade were important.

4 Fib:

Location: Corresponds to modern Fife.

Characteristics: Fib, a peninsula in eastern Scotland, had rich agricultural lands and a strategic location, making it a significant economic and political hub. It also had a developed coastline, serving as a trade center.

5Fidach:

Location: Its exact location is unknown but speculated to be near Inverness.

Characteristics: Information about Fidach is limited, but it may have been situated in a highland area, with livestock herding and hunting as primary livelihoods.

6Fotla:

Location: Now known as Atholl (Ath-Fotla).

Characteristics: Fotla was in the central highlands, characterized by mountainous terrain and extensive forests. Being a remote area, it likely maintained unique cultural and traditional practices.

7 Fortriu:

Location: Associated with the Roman Verturiones and recently centered around Moray.

Characteristics: Fortriu was a particularly significant region in Pictland, serving as a center for politics and military. Its fertile land and strategic position gave it considerable influence over surrounding areas.

キャット(Cait):

位置: 現代のカイスネスとサザーランドに相当します。

特徴: キャットはスコットランドの北端に位置し、海岸線と広大な高地が特徴的です。この地域は古代から漁業や農業が盛んで、強固な地域社会を築いていたと考えられます。ケー(Ce):

位置: 現代のマーとブキャンに位置しています。

特徴: ケーはスコットランド東部の豊かな農地帯に位置し、農業や牧畜が重要な経済活動であったと推測されます。また、交易路の中心地としても機能していた可能性があります。サーキン(Circin):

位置: 恐らく現在のアンガスとメアンズに位置していました。

特徴: サーキンは肥沃な土地と良質な農地で知られ、穀物生産が盛んであったとされます。また、海岸線に近いことから、漁業や貿易も重要であった可能性があります。フィブ(Fib):

位置: 現代のファイフにあたります。

特徴: フィブは、スコットランドの東部に位置する半島地域で、豊かな農地と戦略的な位置から、重要な経済・政治の中心地であったと考えられます。海岸線が発達しており、交易の拠点でもありました。フィダック(Fidach):

位置: 正確な場所は不明ですが、インヴァネス近辺と推測されています。

特徴: フィダックに関する情報は限られていますが、高地地域に位置していた可能性があり、牧畜や狩猟が主な生活手段であったと考えられます。フォトラ(Fotla):

位置: 現代のアソル(Ath-Fotla)に相当します。

特徴: フォトラは中央高地地域に位置し、山がちな地形と広大な森林が特徴です。この地域は遠隔地であり、独自の文化や伝統を保持していた可能性があります。フォートリウ(Fortriu):

位置: ローマ人のヴェルトゥリオネスに相当し、最近ではモレイを中心とする地域とされています。

特徴: フォートリウはピクトランドの中でも特に重要な地域で、政治・軍事の中心地であったとされます。

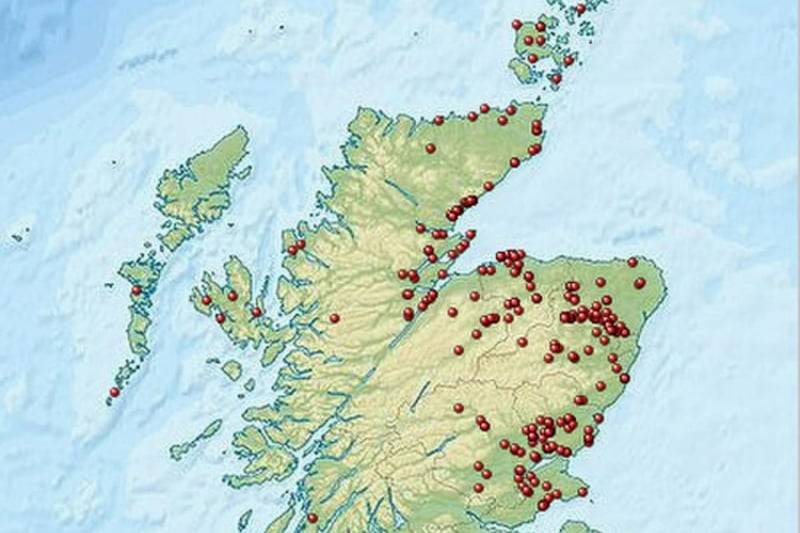

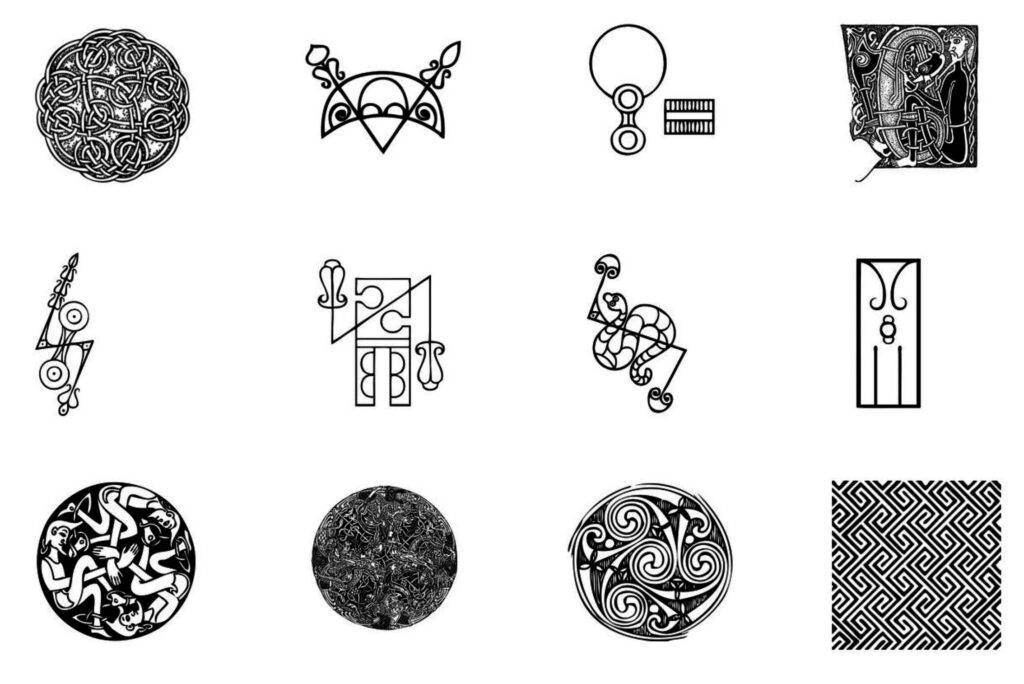

Scotland is home to over two hundred stones adorned with unique Pictish symbols, predominantly found in the Highlands. These enigmatic symbols have long contributed to the intrigue surrounding the Pictish civilization. Contemporary archaeologists and historians have proposed theories regarding their meanings and the reasons behind the erection of these stones. The symbols are distinct, typically depicting realistic animals, geometric patterns, and common objects. Often, these symbols are found in pairs on stones such as The Eagle Stone, The Gairloch Stone, and The Skinnet Stone at the North Coast Visitor Centre. The recurrent nature of these symbols has led to the widely accepted theory that they constitute a codified system of ‘writing,’ possibly denoting personal names.

It’s hypothesized that these symbols might represent various Pictish clans and lineages, with the stones indicating alliances among these groups. Alternatively, they could have marked marriages among prominent families, served as gravestones, or functioned as territorial markers.

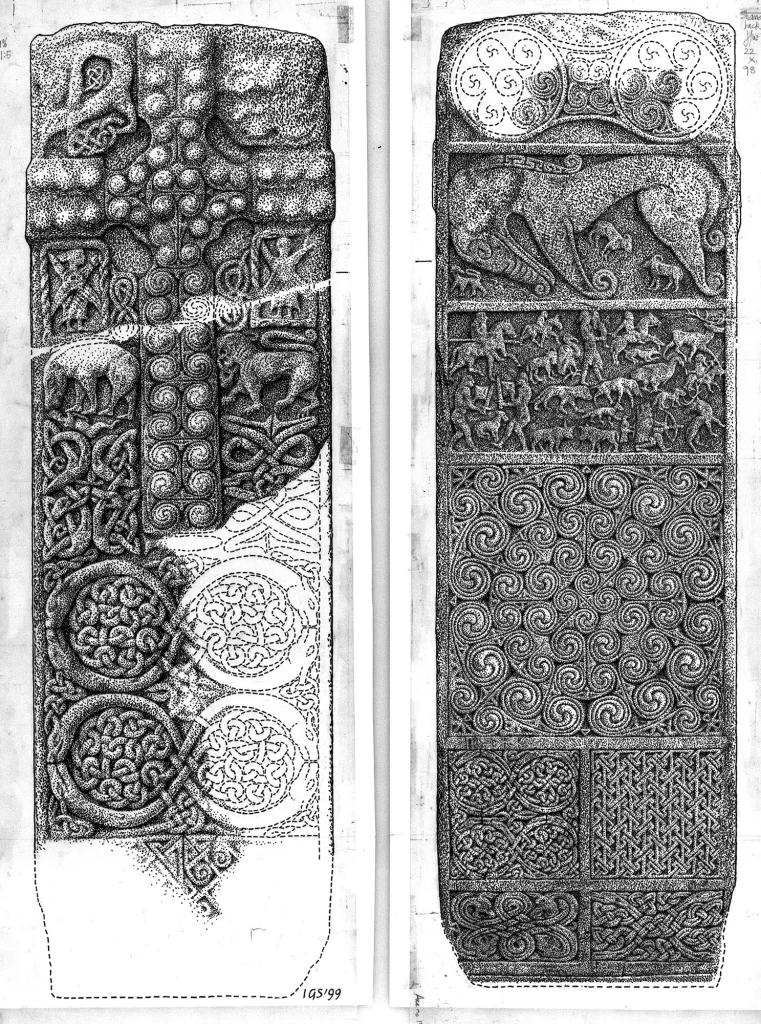

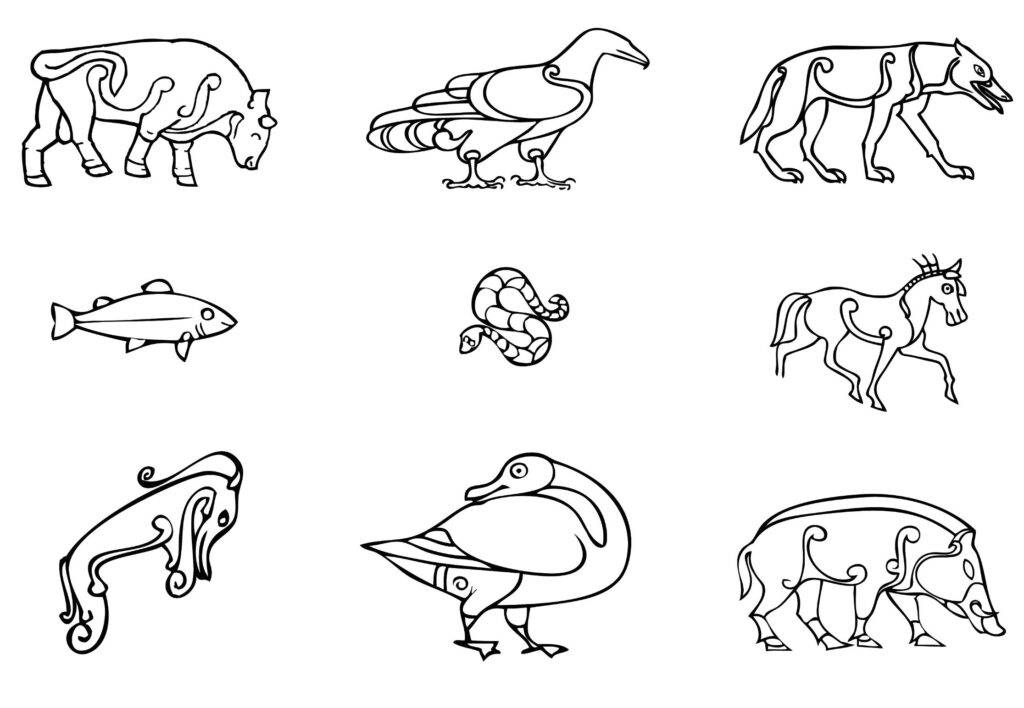

Among these Pictish stones, certain ones feature specific animals, like the boar on The Knocknagael Boar Stone or the wolf displayed in the Inverness Museum and Art Gallery from Ardross. The cross-slabs, dating to around the 700s AD, often depict animals in royal hunting scenes, as seen in Hilton of Cadboll. These animals range from realistic depictions to mythical creatures, like those beneath the cross arms of the Shandwick Stone.

One particularly enigmatic symbol is the ‘Pictish beast.’ Frequently appearing on carved stones across both northern and southern Pictish regions, this symbol has puzzled experts due to its unusual design. While some suggest it may represent a marine mammal, possibly a dolphin or whale, its distinctiveness, especially compared to the other more lifelike animal carvings, continues to intrigue scholars and enthusiasts alike.

スコットランドには、ハイランド地方を中心に、ピクト族の象徴が刻まれた200以上の石碑が存在します。これらの神秘的な象徴は、長い間ピクト族の文明に対する興味をかき立ててきました。現代の考古学者や歴史学者は、これらの象徴の意味や石碑が立てられた理由についての理論を提唱しています。象徴は独特で、実在する動物、幾何学的な模様、一般的な物体などが描かれています。これらの象徴はしばしばペアで見られ、例えばノースコーストビジターセンターのイーグルストーン、ゲアロックストーン、スキネットストーンなどがあります。これらの象徴が繰り返し登場することから、一般的には個人名を表す「記述システム」としての役割を果たしていると考えられています。

これらの象徴は、ピクト族のさまざまな氏族や系統を表しているという説があり、石碑はこれらの集団間の同盟を示している可能性があります。また、重要な家族間の結婚を記録するため、墓石として、あるいは領土の境界標として機能していたかもしれません。

特定のピクト族の石碑には、ノックナゲールボアストーンの猪や、インバネス美術館のアードロスの狼など、特定の動物が描かれています。紀元700年頃の後期に制作されたクロススラブには、カドボルのヒルトンで見られるように、王族の狩猟シーンで動物が特徴づけられています。これらの動物は、実在する生き物から、シャンドウィックストーンのクロスの腕の下にあるような神話上の獣に至るまで、さまざまです。

特に謎めいた象徴として「ピクト獣」があります。これはピクト族の彫刻石碑に最も一般的に現れる象徴の一つで、北部と南部のピクト地域の両方で見られます。その珍しいデザインから、専門家の間で多くの議論がなされています。一部の専門家は、それが海洋哺乳類であり、頭から水を流しているイルカやクジラを表していると解釈しています。ピクト族の彫刻石碑に登場する他の動物象徴が非常にリアルであることを考えると、この「ピクト獣」の奇妙なデザインは引き続き学者や愛好家の関心を集めています。

Across Scotland, particularly in the Highlands, there exist over two hundred stones featuring Pictish symbols, contributing to the enigmatic aura surrounding the Pictish civilization. Modern archaeologists and historians have made strides in interpreting these symbols and their purpose. The symbols are distinctive, often depicting animals, geometric patterns, and common objects. Many stones, such as The Eagle Stone, The Gairloch Stone, and The Skinnet Stone at the North Coast Visitor Centre, display these symbols in pairs. This repetitive nature has led to the belief that they may have been part of a coded ‘writing system’ for naming individuals. It’s theorized that these symbols could represent various Pictish clans and lineages, with the stones indicating alliances among these groups. They might also have marked marriages between significant families, served as gravestones, or acted as territorial markers.

Specific animals are featured on some Pictish stones, like The Knocknagael Boar Stone or the wolf at the Inverness Museum and Art Gallery from Ardross. Cross-slabs dating back to around the 700s AD depict animals in royal hunting scenes, such as at Hilton of Cadboll, and sometimes mythical creatures beneath the cross arms of the Shandwick Stone.

The ‘Pictish beast’ stands out as one of the most peculiar and commonly seen creatures on Pictish stones, found across both northern and southern Pictish regions. While some experts believe it might represent a marine mammal, possibly a dolphin or whale, its unique design, contrasting with the realistic depictions of other animals, adds to its fascination.

スコットランド、特にハイランド地方には、ピクト族の象徴が描かれた200以上の石碑が存在し、これらはピクト族の神秘的な雰囲気に一役買っています。現代の考古学者や歴史学者は、これらの象徴の解釈と目的について進展を遂げています。これらの象徴は独特で、動物、幾何学的なパターン、一般的な物体などが描かれています。イーグルストーン、ゲアロックストーン、ノースコーストビジターセンターのスキネットストーンなど、多くの石碑にはこれらの象徴がペアで描かれています。この繰り返しの性質から、これらが個人の名前を記すための暗号化された「書記システム」の一部であると考えられています。これらの象徴は、ピクト族の様々な氏族や系統を表しており、石碑はこれらのグループ間の同盟を示している可能性があります。また、重要な家族間の結婚を記録したり、墓石や領土の境界標として機能していた可能性もあります。

特定の動物が描かれたピクト族の石碑もあります。例えば、ノックナゲールボアストーンや、インバネス美術館とアートギャラリーのアードロスの狼などです。紀元700年代に遡るクロススラブには、カドボルのヒルトンのように、王族の狩猟シーンに動物が描かれています。時には、シャンドウィックストーンのクロスの腕の下に描かれた神話上の生き物のように、想像上の生物も描かれています。

「ピクト獣」は、ピクト族の石碑に描かれた中でも最も特異で一般的な生き物の一つです。北部と南部のピクト地域の両方に存在するこの生き物について、一部の専門家は海洋哺乳類、おそらくは頭から水を噴出するイルカやクジラを表していると考えています。他の動物の象徴が現実的に描かれていることとの対比から、この「ピクト獣」の独特なデザインは大きな興味を引いています。

Across Scotland, particularly in the Highlands, there exist over two hundred stones featuring Pictish symbols, contributing to the enigmatic aura surrounding the Pictish civilization. Modern archaeologists and historians have made strides in interpreting these symbols and their purpose. The symbols are distinctive, often depicting animals, geometric patterns, and common objects. Many stones, such as The Eagle Stone, The Gairloch Stone, and The Skinnet Stone at the North Coast Visitor Centre, display these symbols in pairs. This repetitive nature has led to the belief that they may have been part of a coded ‘writing system’ for naming individuals. It’s theorized that these symbols could represent various Pictish clans and lineages, with the stones indicating alliances among these groups. They might also have marked marriages between significant families, served as gravestones, or acted as territorial markers.

Specific animals are featured on some Pictish stones, like The Knocknagael Boar Stone or the wolf at the Inverness Museum and Art Gallery from Ardross. Cross-slabs dating back to around the 700s AD depict animals in royal hunting scenes, such as at Hilton of Cadboll, and sometimes mythical creatures beneath the cross arms of the Shandwick Stone.

The ‘Pictish beast’ stands out as one of the most peculiar and commonly seen creatures on Pictish stones, found across both northern and southern Pictish regions. While some experts believe it might represent a marine mammal, possibly a dolphin or whale, its unique design, contrasting with the realistic depictions of other animals, adds to its fascination.

スコットランド、特にハイランド地方には、ピクト族の象徴が描かれた200以上の石碑が存在し、これらはピクト族の神秘的な雰囲気に一役買っています。現代の考古学者や歴史学者は、これらの象徴の解釈と目的について進展を遂げています。これらの象徴は独特で、動物、幾何学的なパターン、一般的な物体などが描かれています。イーグルストーン、ゲアロックストーン、ノースコーストビジターセンターのスキネットストーンなど、多くの石碑にはこれらの象徴がペアで描かれています。この繰り返しの性質から、これらが個人の名前を記すための暗号化された「書記システム」の一部であると考えられています。これらの象徴は、ピクト族の様々な氏族や系統を表しており、石碑はこれらのグループ間の同盟を示している可能性があります。また、重要な家族間の結婚を記録したり、墓石や領土の境界標として機能していた可能性もあります。

特定の動物が描かれたピクト族の石碑もあります。例えば、ノックナゲールボアストーンや、インバネス美術館とアートギャラリーのアードロスの狼などです。紀元700年代に遡るクロススラブには、カドボルのヒルトンのように、王族の狩猟シーンに動物が描かれています。時には、シャンドウィックストーンのクロスの腕の下に描かれた神話上の生き物のように、想像上の生物も描かれています。

「ピクト獣」は、ピクト族の石碑に描かれた中でも最も特異で一般的な生き物の一つです。北部と南部のピクト地域の両方に存在するこの生き物について、一部の専門家は海洋哺乳類、おそらくは頭から水を噴出するイルカやクジラを表していると考えています。他の動物の象徴が現実的に描かれていることとの対比から、この「ピクト獣」の独特なデザインは大きな興味を引いています。

With the advent of Christianity around 600 AD, Pictish art witnessed a transformation, introducing new imagery and motifs influenced by Christian themes. The remarkable artistry linked with the Picts, largely attributed to Christian inspiration, continued to thrive. The practice of erecting stone monuments persisted as a significant cultural and identity marker. The carvings on these stones grew more intricate, featuring detailed work on both sides of the stones, predominantly in relief, with Christian crosses being a prominent feature. Notable examples include the Rosemarkie Stone at Groam House Museum and the Ballachly Stone at Dunbeath Heritage Centre. Moreover, some stones display elaborate scenes with human and animal figures, like The Shandwick Stone, or depict biblical narratives, such as the Nigg Stone illustrating the tale of St Paul and St Anthony receiving holy bread from a raven in the desert.

Pictish cross-slabs are often likened to the pages of illuminated manuscripts, such as the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels, particularly in their stylistic animal depictions and interlacing patterns, also common in Class II stones. These cross-slabs resemble contemporary luxurious jewelry in their imagery. One can easily envision the Rosemarkie stones at Groam House Museum adorned with gold filigree or vibrant enamel. The Rosemarkie cross slab resembles a narrow book, its intricate decorations akin to the lavish treasure bindings seen in some Early Medieval Gospel Books. It’s conceivable that all these cross-slabs were once coated with a thin layer of plaster and painted, which would have added vivid colors to their surfaces, making them a spectacular sight.

紀元600年頃からのキリスト教の導入は、ピクト族の芸術に新しいイメージとテーマをもたらしました。ピクト族と関連付けられる素晴らしい芸術的な技術の多くは、キリスト教の信仰によって触発されました。石の記念碑を作る習慣は、文化とアイデンティティの非常に重要な表現として残りました。彫刻はより複雑になり、特別に形作られた石の両面に施され、装飾はほぼ常に浮き彫りで、主要な要素はキリスト教の十字架でした。グロームハウス博物館のローズマーキーストーンやダンビースヘリテージセンターのバラクリーストーンは良い例です。しかし、シャンドウィックストーンのような人間や動物の図の複雑なシーンや、聖パウロと聖アンソニーが砂漠で神聖なパンをカラスによって運ばれる話を描いたニッグストーンのような聖書の物語や場面を描いた石もあります。

ピクト族のクロススラブはしばしば、ケルズの書やリンディスファーン福音書のような装飾写本のページと比較されています。これらの写本のページは、動物やインターレースのスタイルにおいてピクト族の石碑、特にクラスIIの石碑と明らかな類似点があります。いくつかのクロススラブは、豪華な現代の宝石類のイメージを想起させます。グロームハウス博物館のローズマーキーストーンが金のフィリグリーや多色のエナメルで装飾されていることを容易に想像できます。ローズマーキーのクロススラブは狭い形の本のように見え、その精巧に装飾された形は、初期中世の福音書に残る豪華な宝石の装丁に似ています。すべてのクロススラブは、薄い石膏の層で覆われ、その表面に鮮やかな色をもたらすために塗装されていた可能性があります。もしそうであれば、それらは本当に壮観だったでしょう。

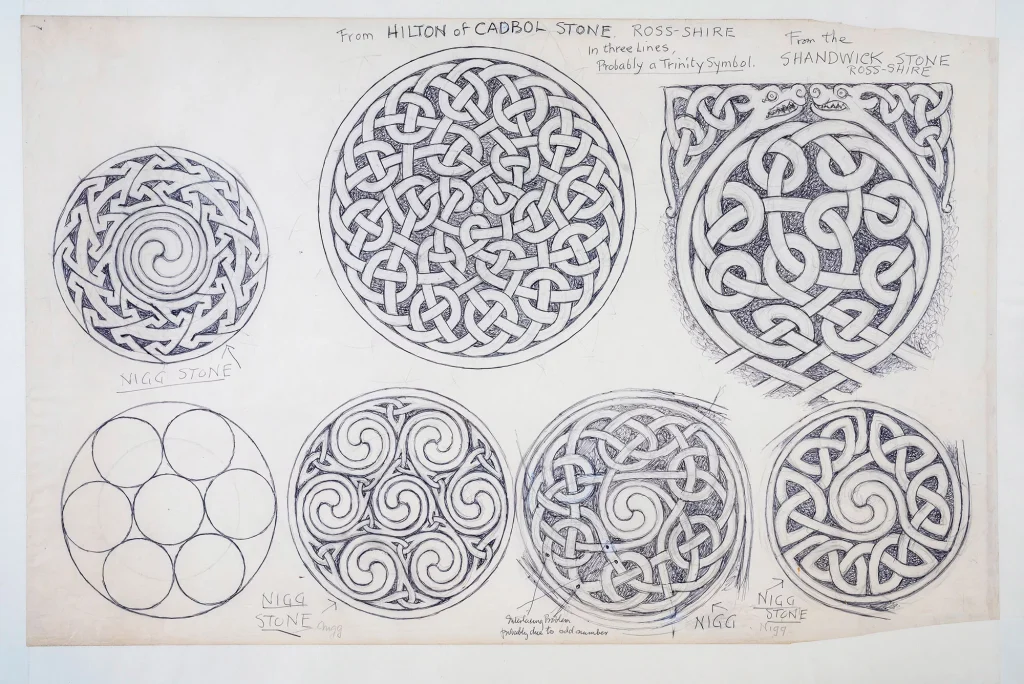

For over a century, Pictish art has been a source of inspiration for artists and craftspeople, playing a pivotal role in the Celtic art revival of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A notable figure in this movement was George Bain (1881-1968), an artist and educator whose Celtic art instruction manuals, first published in 1945, have influenced a multitude of artists and craftspeople.

Bain was deeply fascinated by the complex designs of Pictish stones, early medieval illuminated manuscripts, and the ornate metalwork from Britain and Ireland. He meticulously documented these designs and developed a methodology for replicating them in a series of straightforward steps. Bain’s intention was for others to use his techniques to forge new Celtic-style designs, thereby fostering a unique Scottish national art form and invigorating the rural economy. His instructional methods were disseminated through a series of popular manuals from 1945 onwards, continuing to inspire artists and craftspeople to this day. These manuals are still available under the title “Celtic Art: The Methods of Construction.”

The George Bain Collection, housed and meticulously maintained by the Groam House Museum, is recognized as a Collection of National Significance to Scotland. This collection encompasses Bain’s original sketches, the hand-drawn plates for his books, various craft designs, and the crafts themselves, including carpets, leatherwork, woodwork, embroideries, and ceramics. It offers a unique glimpse into Bain’s creative process, his pedagogy and advocacy for Celtic art, the impact of his publications, and how his personal life mirrored his dedication to and philosophy of Celtic art.

ピクト族の芸術は、1世紀以上にわたり芸術家や職人たちに影響を与えてきましたが、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてのケルト芸術復興の中心となりました。ジョージ・ベイン(1881-1968年)は、1945年に初版が出版されて以来、数え切れないほどの芸術家や職人たちに影響を与えたケルト芸術の指導マニュアルの作者であり、芸術家で教育者でもありました。 ベインは、複雑なピクト族の石碑、初期中世の装飾写本、そしてイギリスとアイルランドの華麗な金属工芸に魅了されました。彼はこれらのデザインの詳細な図を描き、シンプルな手順の連続で描くことができる方法を作り出しました。ベインは、他の人々が彼の方法を使ってケルト様式の新しいデザインを作り、独自のスコットランドの国民芸術を促進し、地方経済を刺激することを望んでいました。1945年以降、彼は彼の方法を人気のある指導マニュアルのシリーズで出版し、今日でも芸術家や職人たちに影響を与え続けています。現在、彼の指導マニュアルは「ケルトアート:構築方法」として引き続き印刷されています。

ジョージ・ベイン・コレクションはグロームハウス博物館が管理しており、スコットランドにとっての国家的重要性を認められたコレクションです。このコレクションには、ベインのスケッチ、彼の本のための手描きのプレート、工芸品のデザイン、そして工芸品自体(カーペット、革製品、木工品、刺繍、陶器)が含まれています。コレクションは、ジョージ・ベインの作業方法、彼の教え、ケルト芸術への提唱、彼の出版物の影響、そして彼の家庭生活が彼のケルト芸術へのコミットメントと哲学をどのように反映しているかについて、ユニークな洞察を提供します。

PICTISH SYMBOL From the George Bain Collection ©Groam House Museum

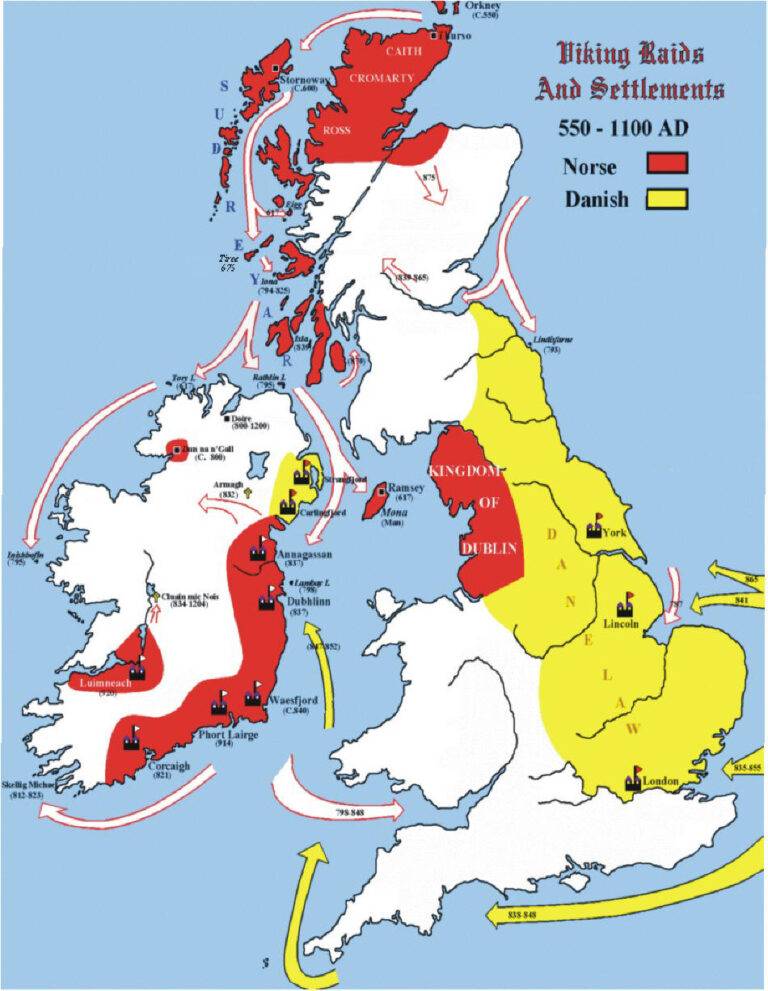

793年、バイキングが初めてブリテン島に到着したことが記録されています。この歴史的な出来事は、リンディスファーン修道院への襲撃によって特徴づけられました。この襲撃は、「アングロ・サクソン年代記」という重要な中世初期の英国史の資料に記録されており、西ヨーロッパにおける最初の記録されたバイキングの侵攻とされています。リンディスファーンは、当時、キリスト教の学びと文化の重要な中心地で、イングランド北東沿岸の島に位置していました。バイキングによるこの攻撃は、略奪を目的とした残忍な襲撃であるだけでなく、聖地への衝撃的な攻撃でもあり、バイキングがブリテン島史においてどのように捉えられるかという点での転換点を示しました。

スコットランドに関しては、最初のバイキングの到達が約875年頃とされています。この時期には、ノルウェーのハーラル1世王(ハーラル美髪王とも呼ばれる)が船隊を率いてスコットランドに到着しました。彼の目的は単なる探検や略奪ではなく、より広範な征服と支配のキャンペーンの一環でした。ハーラル王の行動には、地元の反乱の鎮圧と彼の影響力の地域への拡大が含まれていました。このノルマンの影響と定住は、沿岸の襲撃にとどまらず、特にスコットランド東部のアバディーンシャー地方において、政治的および文化的な影響をもたらしました。ノルマンの影響は、スコットランドでのさまざまな考古学的発見、地名、地元文化の側面に明らかであり、彼らの長期的な存在とスコットランド史への統合を示しています。

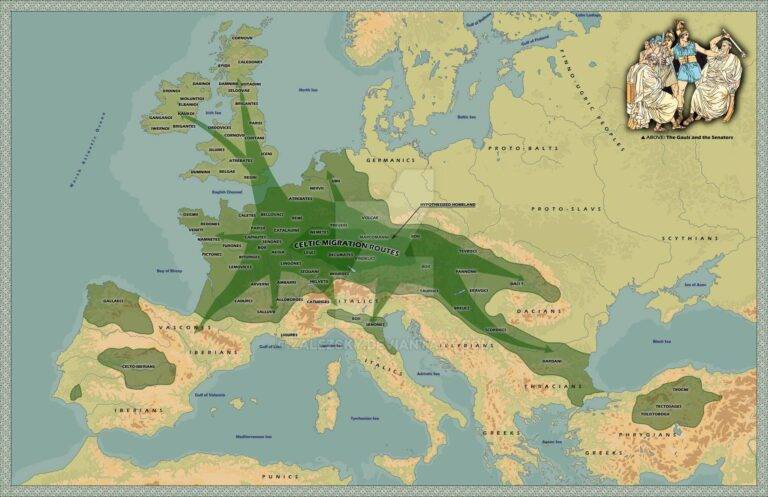

TUNIC : WHAT DID VIKINGS (GERMANIC PEOPLE) WEAR?

大多数のアイルランド人のY染色体は,一つの家系に属するものだとされるが,その一族は「オシーン」(3世紀の伝説上の英雄・詩人)と名付けられる.サイクスは,この「オシーン」の一族がアイルランド各地域のY染色体に占める割合を出している.最も高いのが北西部のコナハトで98%,次に高いのが南西部のマンスターで95%,北東部のアルスターは81%,最も低いのが南東部のレンスターで73%となっているさらに興味深いことにサイクスは,アイルランド人男性の圧倒的多数がもっている「オシーン」のY染色体が,スペインのバスク地方やガリシア地方の調査でも見られることを指摘し,「アイルランドとスペインの間には遺伝学的結びつきがある」と主張する Y染色体は,オークニー諸島とシェトランド諸島を除くスコットランドやウェールズでも多く見られ(スコットランド全体で72.9%,ウェールズ全体で83.2%,イングランド全体でさえ64%を占める),その分布はアイルランドとブリテン島南西部(ウェールズとコーンウォール)に集中している 「アイルランドのケルト人」の大部分は,農耕が始まった頃にイベリア半島から移住した人たちで,ブリテン諸島が切り離される前にヨーロッパ大陸から来ていた中石器時代(約1万1500年前~約6000年前)の人たちと一緒になった アイルランド人の起源に関するオッペンハイマーの見解であるが,最近の研究状況について,「アイルランドへの(鉄器時代の)ケルト人移住の考えを今も受け入れている考古学者と歴史家を探すことは難しくなってきている」と述べ,「私の分析から鉄器時代に移住したという遺伝学的証拠はない」と言い切っている サイクスと同じく,彼も遺伝学的見地から,従来の「ケルト」移住説を否定する.そして,やはりスペインとの強い関係を指摘するのである.彼の分析によると,ブリテン諸島の人々の75~95%が遺伝学的にイベリア半島出身者と一致し,アイルランド,ウェールズの海岸側,スコットランドの中部と西岸はほとんどすべてイベリア半島出身者で構成される12).オッペンハイマーは,ブリテン諸島の先祖の4分の3は,最初の農民が現れるはるか昔にこの地に到着していたとし,比率としては,全体で72.6%,アイルランドでは87.9%,ウェールズでは81.1%,コーンウォールでは78.8%,(付随する島々を含む)スコットランドでは70.1%,イングランドでは67.7%という数字を出している